Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover InterContinental New York Barclay Hotel, where Ernest Hemingway finalized the draft of his famous novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

InterContinental New York Barclay Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2025, dates to 1926.

VIEW TIMELINE

InterContinental New York Barclay Animation

WATCH NOWIn the early 20th century, the area around New York City’s famed Grand Central Terminal—then called “Terminal City”—had emerged as a prime location for widespread real estate projects. Seeking to capitalize on this burgeoning economic opportunity, the New York Central Railroad obtained a parcel of land on the west side of Lexington Avenue between 48th and 49th Streets. The company subsequently sought to lease the plot for commercial development, agreeing to a deal with a syndicate known as the “Barclay Park Corporation.” Led by architect Eliot Cross and entrepreneur William Seward Webb Jr., the ambitious group hoped to create an exclusive, 600-unit housing complex on the site. But their plans started to change once they noticed the surging number of travelers passing through the district by way of Grand Central Terminal. The Barclay Park Corporation thus decided to build a luxurious 14-story apartment hotel instead, intending for the business to eventually become the envy of all Midtown Manhattan. Using additional financial assistance from the storied Vanderbilt family, the Barclay Park Corporation subsequently began raising the nascent structure on behalf of the New York Central Railroad during the mid-1920s. Renowned firm Cross and Cross specifically oversaw the hotel’s stunning design, which featured a masterful combination of architectural styles like Federal and Renaissance Revival.

Following months of diligent work, the Barclay Park Corporation’s highly anticipated hotel made its triumphant debut in 1926. Referred to simply as “The Barclay,” the destination quickly gained a reputation for its unrivaled elegance and glamour. Occupancy was practically full every night, as countless vacationers eagerly booked any available suites for weeks at a time. In fact, some of the country’s most illustrious cultural icons were soon frequently seen at the Barclay, including influential entertainers, intellectuals, and business leaders. Prominent industrialists Walter W. Law and William Henry Barnum were among the first tenants of the new Barclay, as well as actor Charles Ray and composer Amy Beach. Over the following decades, the hotel’s guestbook would feature the names of many other celebrities, such as Marlon Brando, Bette Davis, and Gloria Swanson. Revered author Ernest Hemingway even finished the final portions of his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, at the Barclay upon his return from Spain in 1940. Nevertheless, the Barclay was forced to modify its operational model as apartment hotels declined in popularity throughout the middle of the century. Additional renovations affected the building during the 1950s and 1960s in turn, which introduced several breathtaking facilities like the English-style grill room called “Kings’ Grill.” More extensive work occurred following Pan Am’s acquisition of the historic hotel via its subsidiary, InterContinental Hotels, in 1978.

Investing an extensive $18 million, InterContinental spent the next four years comprehensively revitalizing the building’s storied guestrooms and public spaces back to their former glory. Rebranded as the “InterContinental New York Barclay,” the renovations proved to help make the building’s reputation soar once again. The greatest symbol of the hotel’s revival was the decision of U.S. President Bill Clinton to stay on-site while campaigning locally for reelection during the mid-1990s. From its early days as part of Terminal City to its modern incarnation as a premier hotel, the InterContinental New York Barclay has managed to endure as one of New York City’s most elite retreats. InterContinental Hotels Group has remained central toward maintaining this incredible standard, too, as evidenced by its investment of another $180 million toward preserving the hotel’s architectural integrity in 2014. Indeed, the hotel’s dedicated management team spent the next two years diligently refurbishing every available guestroom and suite, so that they displayed an exquisite Park Avenue-residential style. Furthermore, the 20,000-square-feet meeting space saw its terrific architectural character preserved, while also updating its amenities to better meet the standards of a contemporary audience. Celebrating its centennial anniversary in 2026, the InterContinental New York Barclay will truly be a place that every cultural heritage traveler can enjoy for generations to come.

-

About the Location +

InterContinental New York Barclay resides in the heart of Midtown Manhattan, one of New York City’s most famous areas. Home to renowned landmarks like Central Park, Times Square, and Carnegie Hall, the locale is the middle portion of the greater borough of Manhattan. Often described today as the cultural capital of the world, Manhattan’s origins are quite humble. The Lenape Native Americans had long inhabited the region for centuries, referring to it as “manaháhtaan,” or “the place for gathering wood to make bows.” But in 1609, Henry Hudson—and English explorer working on behalf of the Dutch East India Company—became the first European to chart Manhattan’s coastline (which was also an island). The Dutch had hoped Hudson could locate the mythical “Northwest Passage,” a maritime route that was believed to cut through the North American landmass straight to Asia. Despite Hudson’s failure in locating the illusive body of water, the Dutch nonetheless took his findings to establish a colony in 1625. Building a citadel called “Fort Amsterdam” at the southernmost tip of Manhattan, the Dutch eventually used the island to serve as the economic hub for their settlement of New Amsterdam. (According to one merchant, Pieter Janszoon Schagen, the first colonists to arrive apparently paid the Lenape for the island in exchange for a fixed sum of Dutch guilders.) New Amsterdam then quickly emerged as an important hub for trade between the Caribbean, Europe, and several other North American colonies.

It remained under Dutch authority for the next four decades, until the English managed to wrestle control away during the Second Anglo-Dutch War of the 1660s. Besides a moment in which the Dutch recaptured Manhattan, the island continued to serve as the center of the English Province of New York for decades. As such, the community on Manhattan Island was renamed as “New York City.” Manhattan and the surrounding communities near New York Harbor steadily grew as a prosperous seaport under English rule. It became a focus for development in the “New World,” with both Columbia University and The King’s College being founded during that period. The area continued to play a significant role in New York, especially during the American Revolution. The island became a hotbed for patriotic sentiment, with the Sons of Liberty organizing in the city to protest British efforts on taxation without representation. Dozens of revolutionaries even met in Manhattan to hold a Stamp Act Congress, which constituted the first formal effort by Americans to resist the colonial authorities. Its socioeconomic significance also made it an early military target of the United Kingdom when fighting finally broke out between the two sides in the mid-1770s. In fact, the British attempted to seize it during the New York Campaign. George Washington and the Continental Army were unfortunately forced to abandon Manhattan and its bustling port at the climax of the campaign, which transpired with the defeats at the Battle of Fort Washington and the Battle of Long Island.

Manhattan remained occupied by the British for the remainder of the war, functioning as the main headquarters for its various military expeditions active throughout the colonies. Once the fighting had stopped in the early 1780s, the region became the fifth national capital for the infant United States of America under the Articles of Confederation. Delegates to the Continental Congress subsequently met at New York City Hall in Lower Manhattan, which at the time was located inside a local business called “Fraunces Tavern.” Manhattan remained the capital of the nation when the U.S. Constitution was enacted in 1789, gathering inside the now famous “Federal Hall.” Federal Hall specifically served as the site where the federalized U.S. Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court met, as well as the place where both the Bill of Rights and Northwest Ordinances were ratified! Even though Manhattan ceased serving as the nation’s capital a year later, it remained a vibrant economic center well into the 19th century. Thanks to the financial policies of Alexander Hamilton (who also called New York City his home) and the development of the Erie Canal, New York City emerged as the main port for any goods heading toward either Canada or the American Midwest. The New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street matured as a result, evolving into one of the nation’s leading financial institutions. Its population exploded, surpassing Philadelphia in both size and prosperity. Its wealth of economic opportunities made it a desirable destination for all kinds of immigrants, beginning first with German and Irish people and later Southern and Eastern Europeans.

Manhattan thus became densely populated near the end of the century, with hundreds of tenement houses lining most of its local neighborhoods. But the presence of so many immigrant families in Manhattan led to the development of numerous ethnic enclaves—like Little Italy—as well as the perception that the island was a beacon for those wishing to gain a better life in the United States. (This vision even inspired the French to donate the Statue of Liberty to America in 1886.) Manhattan continued to attract waves of migrant peoples into the 20th century as well, namely African Americans who relocated to the area as part of the Great Migration of the 1920s. This led to the birth of the celebrated Harlem Renaissance, which was an intellectual movement that saw the cultural revival of African American art and literature in the United States. Although it was concentrated in the Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem, its influence was so great that it affected black artists, musicians, and writers across the globe. With millions of people living in Manhattan by the late 1890s, city officials decided to unite the nearby communities in Brooklyn, Queens, Westchester, and Richmond counties to form the “City of Greater New York.” However, the island became the site for another equally important historical development—industrialization. Around the same time modern New York City emerged, many capitalists and entrepreneurs began financing massive factories and skyscrapers all over Manhattan.

The island’s skyline transformed significantly during the first few decades of the 20th century, with such famous landmarks—including the Chrysler Building, Grand Central Terminal, and 30 Rockefeller Plaza—opening within that span of time. But its most iconic feature was the Art Deco-inspired Empire State Building. Manhattan also saw the creation of many luxurious storefronts, restaurants, and art galleries, which started attracting tourists from across the country. Some of the most opulent buildings to debut were the theaters and concert halls along Broadway, one of Manhattan’s major thoroughfares. Soon known as the “Theatre District,” sections of Broadway quickly became synonymous with nightlife in the city. By the end of the 20th century, Manhattan and the rest of New York City had collectively established themselves as the most influential urban center in the whole United States. Manhattan has since maintained its prestigious status as a national cultural destination. Indeed, the area serves as home for many fantastic upscale apartment complexes and townhouses in such renowned neighborhoods like SoHo, the Upper West Side, the Upper East Side, and Greenwich Village. Furthermore, many prominent corporations, such as JP Morgan Chase, Bloomberg L.P., Deloitte, MetLife, and Viacom are headquartered in the borough. Four of the nation’s biggest television networks—ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC—are also based in Manhattan. Some of the best vendors also have stores on Fifth Avenue, too, making it a shopping paradise. Even the headquarters for the United Nations is based in Manhattan. Few other places can claim to have such heritage as Manhattan or New York City.

-

About the Architecture +

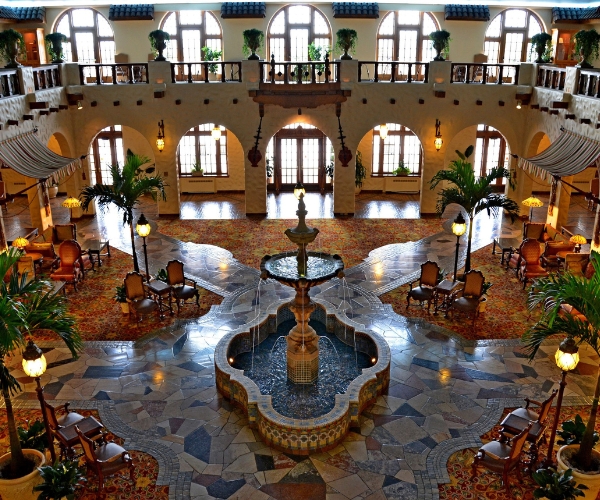

When the InterContinental New York Barclay first opened during the mid-1920s, it stood as a beacon of architectural brilliance and historical charm. The esteemed firm Cross & Cross had overseen its design, creating a stunning 14-story, H-shaped hotel that redefined the surrounding city skyline. To craft its stunning appearance, the architects utilized a wealth of exquisite building materials, including light-colored brick and terracotta trimming. Furthermore, the lower stories of the facade were clad in limestone, adorned with intricate carvings of sea creatures and shells that added a touch of whimsical elegance. The most stunning feature was the main entrance situated on 48th Street, featuring a loggia with three arches, bronze doors, and a marble frame. Upon entering, the lobby exuded a sense of opulence before all who stepped inside. Cross & Cross subsequently crafted the floor out of Bardiglio marble, installing ornate details like black-and-gold border as well as additional marble wainscotting. A carved plaster frieze adorned the walls, too, contributing significantly to the ambiance of the space. Two marble columns supported the ceiling, which featured a stunning Tiffany glass skylight made of amber with ironwork motifs of arrows and stars. The lobby's decor included American colonial-style symbols set against a blue background, further emphasizing the hotel's unique design. The ground floor of the Barclay housed several public spaces and dining areas, too, with the main dining room designed to resemble George Washington's Mount Vernon estate. Even the hotel’s guestrooms radiated this historical eloquence, offering 18th-century inspired aesthetics like quaint fireplaces and rustic décor.

However, the architectural style that best describes the hotel’s overall appearance today as Federal—or at least a more modern take on the aesthetic. Historically speaking, Federal architecture dominated American cities and towns during the nation’s formative years from 1780 to 1840. The name is a tribute to that period, in which America’s first political leaders sought to establish the foundations of the current federal government. Fundamentally, the architectural form had evolved from the earlier Georgian design principles that had influenced both British and American culture throughout most of the 18th century. The similarities between the two art forms have even inspired some scholars to refer to Federalist architecture as a mere refinement of the earlier Georgian aesthetic. Oddly enough though, the architect deemed responsible for popularizing Federal style in the United States was in fact not an American. Robert Adams was then the United Kingdom’s most popular architect, with his work featuring his own distinctive infusion of neoclassical design principles with Georgian architecture. His new variation spread quickly across England, defining its civic landscape for much of the Napoleonic Era. But despite the bitter resentments that most Americans harbored toward Great Britain at the time, their cultural perceptions of the world were still largely influenced by the old mother country. Adams’ new take on Georgian architecture thus rapidly spread across the United States, laying the foundation for the iconic “Federal” architectural style.

Unlike many other popular American architectural forms, Federal style is easily recognizable due to its unique symmetrical and geometric design elements. Most structures created with Federal architecture typically stand two to three stories in height and are rectangular (sometimes square) in their overall shape. While the buildings normally extended two rooms in width, larger structures would usually contain several more. In some cases, circular or oval-shaped rooms functioned as the center of living space. The outside façade of a Federal-style building was simplistic in appearance, although some detailed brass and iron decorations debuted, too. The most common form the ornamentations assumed were elliptical figures and circular or fan-shaped motifs. Architects concentrated on those features around the front entrance, where cornices, metallic molding, and beautifully sculpted fanlight resided. (Fanlights are a regular design element for Federalist buildings, appearing in other locations throughout the top of the structure, as well). The exterior walls themselves were primarily composed of clapboards in the countryside but consisted of brick in urban areas. Palladian-themed windows also proliferated throughout the façade, installed in a way that conveyed a deep sense of balance. The roofing was even hipped and contained simple gables and dormers that allowed natural light to infiltrate the upper echelons of the structure more easily. Many Federal-style buildings still survive in the present, too, with some bearing even listings in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Marlon Brando, actor known for his roles in movies like The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, and A Streetcar Named Desire.

Bette Davis, actress known for her roles in All About Eve, Jezebel, and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?

Gloria Swanson, actress known for her roles in such films like Sunset Boulevard, Sadie Thompson, and Queen Kelly.

Mary Pickford, actress known for her role in the silent film Coquette.

Sherley Temple, child actress known for her roles in Bright Eyes and The Little Princess.

Jimmy Durante, comedian known for his roles in The Great Rupert and It Happened in Brooklyn.

Debbie Reynolds, actress known for her roles in films like Singin’ in the Rain, The Unsinkable Molly Brown, and How the West Was Won.

Charles Ray, actor known for his roles in films like The Pinch Hitter, Getting Gertie’s Garter, and The Courtship of Miles Standish.

Ernest Hemingway, author known for writing such books like A Farwell to Arms and The Old Man and the Sea.

Martha Gellhorn, war correspondent revered for her coverage of various international conflicts like the Spanish Civil War, World War II, and the Vietnam War.

David O. Selznick, film executive best remembered for producing Rebecca and Gone With The Wind.

Amy Beach, first successful American woman to compose large-scale symphonies in the United States.

Walter W. Law, businessman best remembered for founding the renowned Briarcliff Lodge.

Harold S. Vanderbilt, successful philanthropist and businessperson remembered for inventing the contract bridge.

William Henry Barnum, U.S. Senator from Connecticut (1876 – 1879)

Kofi Annan, 7th Secretary-General of the United Nations (1997 – 2006)

Bill Clinton, 42nd President of the United States (1933 – 2001)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

Law & Order (1990 – present)

Spider-Man 2 (2004)

Hide & Seek (2005)

Elementary (2012 – 2019)

Person of Interest: Booked Solid (2013)

Person of Interest: The Perfect Mark (2013)

The Blacklist (2013 – 2023)

Madame Secretary (2014 – 2019)

She’s Funny That Way (2014)

Daredevil (2015 – 2018)

Mr. Robot (2015 – 2019)

Younger (2015 – 2019)

Billions (2016 – 2023)

Homeland: Season Six (2017)

Bull: School for Scandal (2017)

The Deuce (2017 – 2019)

The Good Fight (2017 – 2022)

Deception (2018)

Blindspot: Balance of Might (2018)

FBI (2018 – present)

God Friended Me (2018 – 2020)

Instinct (2018 – 2019)

New Amsterdam (2018 – 2023)

Succession (2018 – 2023)

Evil (2019 – 2024)

Prodigal Son (2019 – 2021)

Ramy (2019 – present)

The Loudest Voice (2019)

40-Love (2021)

Dr. Death (2021)

The Starling (2021)

Suspicion (2022)

Babygirl (2024)

Night Agent (2025)

-

Women in History +

Amy Beach: Among the many illustrious guests to stay at the InterContinental New York Barclay over the years was the renowned composer, Amy Beach. Born Amy Marcy Cheney in 1867, Beach herself hailed from a family that possessed a rich artistic heritage. Her mother, Clara Imogene Marcy Cheney, was an accomplished pianist and singer, and young Amy quickly demonstrated extraordinary musical talents. By the age of one, she could sing forty songs accurately, and by four, she had composed three waltzes for piano—despite not having access to an instrument at her childhood home. Amy's prodigious abilities included perfect pitch and synesthesia, which allowed her to associate musical keys with specific colors. These innate talents enabled her to play music by ear and compose complex pieces mentally before performing them. Her early musical tutoring was guided by her mother, who helped enable her to give public recitals of works by Handel, Beethoven, and Chopin, alongside her own compositions. Then in 1875, the Cheney family moved to Chelsea, Massachusetts, where Amy continued her musical training under the tutelage of Ernst Perabo and Carl Baermann. Despite her parents' decision to forgo a European conservatory education, Amy thrived under local instruction, eventually studying harmony and counterpoint with Junius W. Hill. She also taught herself composition, translating French treatises on orchestration into English.

Nevertheless, the ambitious Amy made her concert debut at sixteen, performing to critical acclaim. Her career flourished, and in 1885, she married Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach, a Boston surgeon and amateur singer. The marriage required Amy to limit her public performances and focus more on composition. Although she missed performing immensely, Amy nonetheless thrived as a composer, with her music debuting across the country in numerous concert halls. Indeed, Amy's compositional success was marked by her Mass in E-flat major, performed by the Handel and Haydn Society in 1892, as well as her Gaelic Symphony that the Boston Symphony covered in 1896. (In fact, the Gaelic Symphony was the first of its kind to be solely compose and published by an American woman.) After her husband's death in 1910, Amy traveled to Europe, where she continued to pursue her musical career. Her European debut in Dresden two years later was well-received, and she gained recognition as a composer of international stature. Returning to America on the eve of World War I, Beach kept composing her music while also advocating for musical education. Amy Beach's final years were thus spent mentoring young musicians and composing at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. She remained active in the music community until her retirement in 1940 due to heart disease, ultimately passing away not long thereafter.