Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Raffles London at The OWO, which once served as the primary headquarters for the influential British War Office.

Raffles London at The OWO, a member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2023, dates back to 1906.

VIEW TIMELINEThe British Army was an incredibly complex organization by the height of the Victorian Era, its many units spread across the globe to protect the colonial territories of the United Kingdom. To administrate its increasingly multifaceted international operations, it relied on a central administrative agency known as the “War Office.” (Although its most modern iteration had been born in 1857, historical records indicate that its origins traced much further back to the reign of King Charles II.) Led by a Secretary of State for War, its hundreds of staff members helped manage everything from the distribution of ordinance to grand strategy. However, the agency’s effectiveness began to wane when it was relocated to several different buildings in Westminster’s Pall Mall. Communication proved to be difficult throughout the campus, with many of the War Office’s personnel forced to act as mere messengers. Seeking to better centralize its disparate departments, the War Office subsequently began investigating prospective sites for a new headquarters large enough to accommodate its entire staff. At first, proposals called for the War Office to share space with the Prime Minister’s Office and then the Admiralty. But factional disputes in Parliament eventually spawned plans to construct a separate facility in Whitehall toward the end of the 19th century.

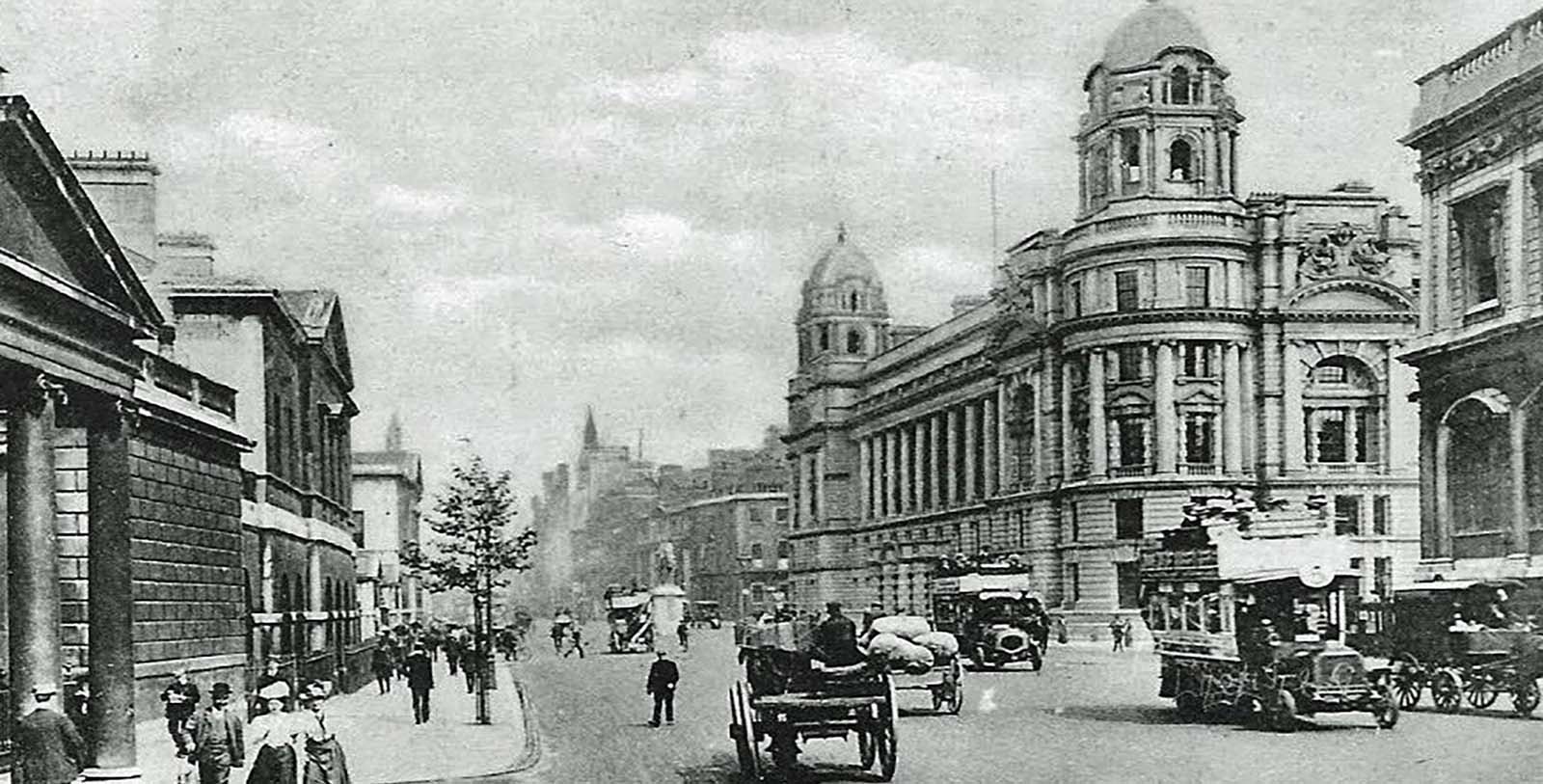

Construction on the War Office’s new home began in 1898, with a respected Scottish architect named William Young overseeing the design. (Young himself is remembered fondly today for creating both the War Office’s headquarters and the Glasgow City Chambers.) Working alongside an architect from the Office of Works—Sir John Taylor—Young spent months diligently creating the structure until his death some two years later. In his absence, Taylor and Young’s son Clyde eventually finished the project in 1907. Despite the abrupt change in leadership, the architectural team had nonetheless managed to build a gorgeous edifice that immediately impressed all who saw it. Indeed, the Youngs and Taylor had developed a marvelous, Baroque-inspired office space with some of the finest building materials available at the time. Resting upon a unique trapezoid-shaped foundation, the structure’s skeleton essentially looked like a massive tank that was up to six feet thick. Some 25 million bricks then encased its exterior walls, as did a combined 29,000 tons of Portland and York stone. Brilliant columns faced the north and western fronts, while various sculptures representing concepts like Peace, War, and Victory adorned the capital. Resting atop the entire building were four magnificent decorative corner domes that loomed majestically over the city. Inside, the structure even featured 1,100 richly detailed rooms that beautifully mimicked the cultural aesthetics of the Age of Enlightenment.

Known simply as the “War Office,” the structure quickly emerged as one of central London’s most iconic landmarks. It also became extremely busy, serving as the site for countless military decisions throughout both World Wars and much of the Cold War. Prominent political figures would even work inside the structure as the Secretary of State for War, including two future British Prime Ministers—David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. Nevertheless, the British government ultimately decided to sell the building into private ownership after operating it for more than a century. In 2014, the modern successor to the War Office agency—the Ministry of Defence—specifically arranged to have the Hinduja Group acquire the historic structure for a generous sum of £350 million. The Hinduja Group immediately set about transforming the building into a luxurious boutique hotel, as well as a series of upscale rental apartments. But the renovations thoroughly revitalized every facet of the building’s brilliant architectural character, too, ensuring that its legacy remained perfectly intact for future generations to appreciate. With the restoration now finished, the erstwhile administrative center is slated to debut as the “Raffles London at the OWO” this summer. (Interestingly, the abbreviation “OWO” is a nod to the building’s previous identity in that it means “Old War Office.”) Currently designated as a Grade II Listed Building, the future of this famous historic site has never looked brighter.

-

About the Location +

Located in the heart of London’s famed Westminster borough, the area of Whitehall has played an essential role in British society for centuries. Indeed, the main thoroughfare—also named “Whitehall”—is host to numerous high-profile government agencies and departments. Its history also harkens back generations, with some of the earliest references to the neighborhood appearing in the Middle Ages. One such account written by noted medieval historian William Fitzstephen indicated that Whitehall had already established a suburban reputation, with its many townhouses situated next to gardens and orchards. Much of the area’s growth seemed to emerge from the increased foot traffic that occurred along Whitehall road, which ultimately led to a waypoint known as the “Holbein Gate.” However, use of the name “Whitehall” was more contemporary in origin, specifically dating to the birth of the famed Palace of Whitehall in the 16th century. Originally a structure called “York Palace,” King Henry VIII had the entire facility redesigned to serve as his official royal residence in 1531. The king subsequently hired the great Flemish artist Anton van den Wyngaerde to oversee the renovation, who based his designs on the appearance of the equally impressive Richmond Palace nearby. The work proved to be a massive undertaking, increasing the size of the complex exponentially to the point where it was one of the biggest structures standing in the region at the time.

Now known as the “Palace of Whitehall,” the sprawling collection of interconnected buildings soon became the cultural center for King Henry VIII’s court. He held numerous events inside the structure, including various sporting matches in venues like a bowling green, a tiltyard, and an indoor tennis courtyard. But the most significant events to occur on-site were royal marriage ceremonies, specifically his second and third weddings to Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour. The Palace of Whitehall remained a fixture among the nobility for many years, continuing to serve as the official royal residence well into the middle of the 17th century. Its strong aristocratic affiliation kept it at the forefront of English (and British) culture, with even the legendary playwright William Shakespeare regularly visiting to host performances of his newest plays on-site. This importance meant that the compound underwent more construction projects, which expanded its size to eventually number more than 1,500 rooms. In fact, the work made the complex the largest of its kind in Europe, eclipsing even the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace. But the Palace of Whitehall also endured moments of tragedy. Following the outbreak of the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarians managed to jail and ultimately execute King Charles I at the location in 1649. Nevertheless, the Royal Family managed to resecure the Palace of Whitehall in the wake of Cromwell’s own death several years later.

The royal association with Whitehall finally came to an abrupt end when a destructive fire swept through the Palace of Whitehall in 1691. With only the gorgeous Banquet Hall surviving the inferno, King William III proceeded to relocate the royal household to Kensington Palace, a few blocks away. Whitehall returned to being an ordinary urban neighborhood, although it soon experienced renewed cultural significance not long thereafter. Beginning as early as the 1750s, the British government opened dozens of offices throughout the neighborhood as part of a strategy to better concentrate its own administration. At first, officials merely rented townhouses to act as their new offices. But as the size of the government grew, so did the need for more space. Government ministers thus sponsored the construction of new buildings to function as the headquarters for organizations like the prestigious Horse Guards. This practice continued unabated well into the 19th and 20th centuries, with many additional agencies relocating to Whitehall, such as the Admiralty and the War Office. Whitehall remains the essential heart of the British government today, serving as the home for the Ministry of Defence, the Department of Health, the Cabinet Office, and others. (The area was even the site of London’s Metropolitan Police, better known as “Scotland Yard.”) In more recent years, Whitehall has emerged as a prominent cultural heritage destination due to its proximity to Westminster Abbey, the Palace of Westminster, and Buckingham Palace. Whitehall has plenty of its own unique attractions to explore, too, including the Banquet Hall and monuments like the Cenotaph.

-

About the Architecture +

The Raffles London at The OWO stands today as a brilliant example of English Baroque Revival architecture. In fact, its gorgeous architectural appearance was a major reason why the British government designated the site a Grade II Listed Building in 1970. Nevertheless, the origins of the Baroque architecture used to design the structure date back to the time of King Edward VII. When King Edward VII assumed the throne upon the death of his mother, Queen Victoria, it marked the beginning of a momentous—albeit brief—period of dynamic cultural expression for British society. Historians today refer to his reign as the Edwardian Era, which lasted from 1901 right up to the outbreak of World War I. Among the advances in art that defined the age was the wholesale embrace of innovative architectural forms. Architects from the United Kingdom were specifically eager to utilize different design philosophies as a means of breaking with the preexisting Victorian standards that had defined British culture for six decades. Looking back to the Age of Enlightenment, they began drawing inspiration from earlier architectural styles like Neoclassicism and Georgian. However, a few professionals—notably Edwin Lutyens, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and Giles Gilbert Scott—looked to the Baroque-inspired work of prominent 17th-century architect Sir Christopher Wren. Replicating Wren’s conservative adaptation of continental Baroque styles, those Edwardian architects created magnificent buildings that displayed a wealth of rich yet somewhat restrained ornamentations. They also incorporated his use of domed corner pavilions, as well as beautiful walls made of stone, brick, and limestone. The decision to re-use such design principles was meant to produce a visual sense of power and amazement in the same way Wren’s designs had generations ago. English Baroque Revival architecture thus became a commonly employed architectural style for numerous public buildings across the United Kingdom, including the historic Old War Office in the heart of central London.

-

Film, TV, and Media Connections +

The Battle of Britain (1969)

The Sweeney: Hearts and Minds (1978)

For Your Eyes Only (1981)

A View to Kill (1985)

License to Kill (1989)

Octopussy (1983)

Skyfall (2012)

The Crown (2016 – 2022)