Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Great Southern Killarney, which was first created by the Great Southern and Western Railway Company in 1854.

Building Ireland Explores the Victorian style of the Great Southern Killarney

The Great Southern Railway Hotel in Killarney, County Kerry, has a fascinating history - it is by all accounts, the world's first hotel built by a railway company at one of their railway stations!

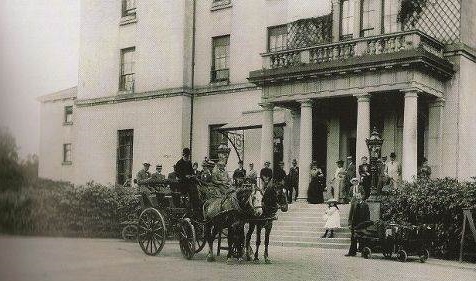

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2019, the Great Southern Killarney is one of County Kerry’s most distinctive holiday destinations. Its history is quite extensive, beginning with the Great Southern and Western Railway Company in the mid-1800s. Among Ireland’s most prestigious businesses during the 19th century, the company desired to develop a rail line that would link Killarney to Dublin. Its first step was to find a 40-acre plot of land upon which to create a train station in downtown Killarney. Along with the station, the railway hoped to build an adjoining hotel to incentivize travel upon the new route. Unfortunately, the area that the railroad company wanted belonged the massive estate owned by the Earl of Kenmare, Sir Valentine Augustus Browne. Lord Kenmare himself was a prominent landowner, whose family estate extended for several thousand miles around Killarney. At first, the Irish nobleman felt apprehensive about the offer, for the construction would destroy a magnificent garden that he had diligently maintained throughout his life. But he eventually agreed under two conditions: that his family would be allowed free rail passage and that all late trains would wait for them to arrive. As soon as these conditions were met, the Killarney Junction Company (a subsidiary of the railroad) quickly set about designing both the station and hotel. The Killarney Junction Company specifically ran a competition to select the best design for the hotel, but for reasons unknown, it chose someone other than the actual winner. Despite not being the first choice, Frederick Daley was ultimately picked to head the design. Daley was still an incredibly talented architect, nonetheless. He had designed portions of Trinity College in Dublin, mainly its Kings Inn Library and Magnetic Observatory.

The hotel finally debuted in July of 1854 as “The Railway Hotel.” The Great Southern and Western Railway Company invested heavily into the hotel’s creation, spending £18,000 just to get the building completed. It immediately became one Ireland’s most prestigious vacation retreat, attracting the likes of Queen Victoria shortly after opening. As the hotel’s popularity grew, so too did its size. The hotel received many renovations throughout the first three decades of the 20th century, which saw the addition of The Picture Room (a photographic dark room) and the Coffee Room. It’s proprietors even formally changed its name to the “Great Southern Hotel Killarney” to highlight its rising national repute. Yet, the hotel’s fortunes declined with the outbreak of World War I. Furthermore, political tumult within Ireland further dampened the economic prospects of the business. In fact, The Free State Army of Ireland seized the hotel during the Irish Civil War, using it as a prison to house political captives. Fortunately, this period of instability proved to be brief. Following its acquisition by the Republic of Ireland, the Great Southern Hotel Killarney continued its ascent as one of Ireland’s best vacation retreats. Many international luminaries from around the world once again visited the location, including First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and Princess Grace Kelly of Monaco. Director David Leen even used The Picture Room to edit his film, Ryan’s Daughter, in 1970. Today, the building is owned by the Scally family, who operates it as the “Great Southern Killarney.” Their stewardship has garnered the hotel with numerous awards, including: “Conference Venue of the Year” at the National Hospitality Awards, “Best Hotel Breakfast” at the 2018 Gold Medal Awards, and “Bar of the Year for Brownes Bar” at the Bar of the Year Awards.

-

About the Location +

Killarney is an ancient Irish town with centuries’ worth of history to its name. While archeological evidence suggests that the earliest people to inhabit the region date as far back as the Bronze Age, the first recorded human settlement appeared in the 7th century with the founding of a monastery. Founded on nearby Innisfallen Island by St. Finian the Leper, it remained occupied for 850 years! (Queen Elizabeth I of England would expel the monks in 1594.) The monastery subsequently became known throughout Europe as a reputable school, giving rise to its moniker as the “Land of Saints and Scholars.” Irish nobles soon made the trek to receive an education from the monks, including the great Irish king, Brian Boru. The priests inside the monastery also endeavored to create all kinds of religious and historical literature, the greatest of which was the celebrated Annals of Innisfallen. Taking some 300 years to write, the Annals of Innisfallen is one of the best medieval manuscripts about early Irish history. Nevertheless, some other tales persist that the village of Aghadoe just outside of modern-day Killarney may, in fact, predate the monastery on Innisfallen Island. Legend states that another Irish saint—Abbán—established his own church in the hamlet some two centuries prior. St. Abbán’s facility was then followed by a second monastery, which was, according to the Annals of Innisfallen, created by St. Finian, too. The tome referred to Finian’s new building as the “Old Abbey.” Some contemporary historians believe that the grounds of the “Old Abbey” may have been a prehistoric pagan ritual site that had attracted spiritual figures for millennia. Nevertheless, scholars today agree that the surrounding environs of Killarney held a significantly mystical quality for the Irish of antiquity.

Following the Anglo-Norman conquest of Ireland in 1169, the new Norman overlords of the land constructed Parkavonear Castle in Aghadoe. As with many other Norman fortifications in Ireland at the time, the castle was meant to serve as a watch tower for any signs of dissention among the native Irish. Nevertheless, the area of modern Killarney remained firmly in the hands of various native clans, although nominal control resided with the Earls of Desmond. Internecine warfare among the local tribes raged without respite, with one family—the MacCarthys—fielding the most powerful armies of all. Within this tumultuous environment, one rival clan of the MacCarthys, the O’Donoghues, constructed the imposing Ross Castle. Located at the edge of Lough Leane, the castle effectively served as the family seat for the O’Donoghues, until it was lost to the MacCarthys amid the Desmond Rebellions. Eventually, the MacCarthys leased the structure to Sir Valentine Browne, whose descendants later became Lords of Kenmare. The MacCarthys themselves developed numerous buildings throughout the area, as well, such as the magnificent Muckross Abbey in 1448. Specifically constructed by Dónal MacCarthy, the abbey served as a friary for the Observantine Franciscans, before it was destroyed by the marauding armies of Oliver Cromwell in 1654. (Ross Castle was similarly sacked by Oliver Cromwell during his conquest of Ireland.) While abbey was never fully rebuilt, it did become an important burial site for several prominent local poets, including O’Donoghue, Ó Rathaille and Ó Súilleabháin. Both Ross Castle and Muckross Abbey are preserved today within Killarney National Park.

Over the centuries, the small market town of Killarney formed around Ross Castle and the various abbeys that dotted the landscape. But the nucleus of the modern Killarney did not fully come into being until Thomas Browne, the 4th Viscount of Kenmare, began investing in its development. Browne granted much longer leases with trivial rents, as a way of encouraging the residents to build better homes. The financial incentives did much to grow the community, which had actually started to become something of a tourist attraction by the end of the 18th century. Despite a brief downturn during the Great Famine of the 1840s, Killarney remained a desirable vacation destination. In fact, Queen Victoria and her royal entourage spent some considerable time at Killarney in 1861. The new business generated from the tourist industry helped introduce even more wealth into the town, which had also become one of the most important economic hubs in western Ireland. Dozens of beautiful homes displaying the most ornate architecture emerged, including the magnificent Muckross House of the affluent Herbert family. Yet, this economic golden era was shattered by the political chaos of the early 20th century. In 1916, Irish republicans staged a week-long revolt against British rule known as the “Easter Rising.” Although the uprising failed, it inspired deep-seeded passions for independence within the hearts of many Irish. The tension erupted some four years later in what became known as the Irish Wars for Independence, in which the Irish Republican Army fought a guerilla war of independence against the British. The conflict played a significant role around Killarney and County Kerry, as republican sentiments ran high. Skirmishes between the two sides happened regularly, including a raid of Great Southern & Western Railway by the Irish Republican Army. The scars from the conflict have long since healed, though. Killarney is once again an amazing holiday destination with a rich heritage that many will enjoy to experience.

-

About the Architecture +

The architecture of the Great Southern Killarney can best be described as being “Victorian” in nature. Due to the growth of the middle classes in the mid-19th century, an increasing number of individuals had access to unprecedented amounts of wealth for the first time. The onset of the Second Industrial Revolution could also make unique, expensive building materials more affordable, due to the technological innovation of mass production. As such, architects could create intricate designs for a much wider audience, giving them far greater creative freedom than they had ever enjoyed in the past. And for the most part, people in the Victorian Era typically wanted to flaunt their newfound affluence. They thus developed a deep appreciation for lavish aesthetics that often embraced ostentatious details. And in some cases, those people revived historic architectural style that they were modified to suit their contemporary tastes. As such, many different architectural styles manifested, including Italianate, Queen Anne, Second Empire, and Gothic Revival. And while the design aesthetics of the Great Southern Killarney are quite varied, its original architect—Frederick Daley—relied upon the Victorian design principles of Classic Revival-style architecture the most. Also known as “Neoclassical,” Classic Revival style borrowed architectural motifs from ancient societies like Rome and Greece. It specifically relied on stylistic design elements that incorporated such structural components like the symmetrical placement of doors and windows, as well as a front porch crowned with a classical pediment. Architects would also install a rounded front portico that possessed a balustraded flat roof. Pilasters and other sculptured ornamentations proliferated throughout the façade of the building, as well. Perhaps the most striking feature of buildings designed with Classical Revival-style architecture were massive columns that displayed some combination of Corinthian, Doric, or Ionic capitals.

-

Famous Historic Events +

Irish War for Independence (1919): For centuries, Ireland had been ruled as a part of England and the United Kingdom. A history of warfare among the Irish, the English, and their allies had spawned deep-seeded feelings for independence throughout Ireland. Occasionally, the tension erupted as violent acts of resistance, such as the Nine Years’ War, the Irish Confederate Wars, and the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Yet, none of those conflict produced an indisputable Irish victory. But as republican sentiments ran high in the Western world during the 19th and early 20th centuries, many Irish patriots felt inspired to try again. In 1916, a group of Irish republicans staged a revolt known as the “Easter Rising,” which proclaimed a self-governing Irish Republic free from British rule. Seizing several important buildings throughout Dublin, the revolutionaries tried to maintain the momentum of their movement. Yet, after a weeks’ worth of fighting, the British Army managed to smash the Easter Rising. Most of the ringleaders were imprisoned and executed in an attempt to suppress another revolt. Unfortunately for the British, the Easter Rising only galvanized popular feelings toward independence. Those passions finally burst forth in a much larger uprising some three years later. The spark that ignited the new rebellion came from the victory of republican party Sinn Féin during Ireland’s general elections of 1918. Led by Éamon de Valera, Sinn Féin and its supporters quickly established a breakaway government—the Dáil Éireann—and formally declared Ireland a sovereign nation called the “Irish Republic.”

Two days following the general election, volunteers within the republic’s paramilitary force—the Irish Republican Army (IRA)—acted on their own initiative and killed two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary. The IRA then proceeded to seize British Army arsenals throughout the countryside. From there, the situation only grew more tenuous as the British Parliament outlawed both Sinn Féin and the Dáil Éireann. In response, the IRA started ambushing British Army patrols across the Irish countryside, and attacked various military installations. An arms race quickly ensued, as London began reinforcing its remaining garrisons with auxiliary units from across the British Isles. Many buildings were also confiscated by British soldiers, who transformed them into garrisons and outposts. Among the buildings converted for military use was the Great Southern Killarney. Sand bags and barbed wire surrounded the hotel, while armed guards patrolled the grounds every day. The British had taken a particular interest in fortifying Killarney, for County Kerry as a whole was a hotbed for republicanism. Violent skirmishes between the British Army and the Irish Republican Army became frequent all over Ireland, as well. Killarney and the surrounding countryside saw its far share of fighting, too, including an IRA raid on the Great Southern & Killarney Railway. In 1921, the British government agreed to a truce with the Irish Republic, leading to the eventual signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. But while the Anglo-Irish Treaty guaranteed Ireland’s autonomy, it still left the nation as a British dominion similar to Canada and Australia. Bitterness over the treaty would remain for generations, resulting in a brief civil war that transpired only a few months later.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Charlie Chaplin, actor known for his silent roles in The Kid and A Woman of Paris.

Robert Mitchum, actor known for his roles in such films like El Dorado, The Night of the Hunter, and Cape Fear.

Tyrone Power, actor know for his roles in such films, like The Mask of Zorro, Witness of the Prosecution, and Blood and Sand.

Éamon de Valera, President of Dáil Éireann (1919 – 1922) and 3rd President of the Irish Republic (1959 – 1973)

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, First Lady to former U.S. President John F. Kennedy (1961 – 1963)

Princess Grace Kelly of Monaco, famous American film actress known for Mogambo and wife of Prince Rainier III.

Queen Sālote Tupou III of Tonga (1918 to 1965)

Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1837 – 1901)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

Ryan’s Daughter (1970)