Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

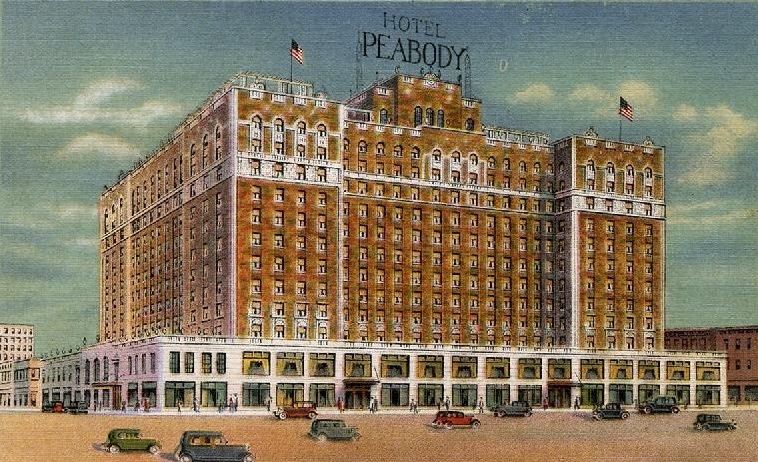

Discover the Peabody Memphis, named after philanthropist George Peabody, which has been a cherished gathering place in Memphis since 1869.

The Peabody Memphis, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 1996, dates back to 1869.

VIEW TIMELINE

History of The Peabody Memphis

The Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of The Peabody Hotel and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg. The Peabody is the Paris Ritz, the Cairo Shepherd's, the London Savoy of this section. Learn more about this fantastic historic hotel here.

WATCH NOWA member of Historic Hotels of America since 1996, The Peabody Memphis is among the handful of hotels to be listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. For good reason, too, as it has stood as cherished holiday destination in downtown Memphis for generations. Following the turmoil of the American Civil War, the residents of Memphis set about the daunting task of reconstructing their beloved city. In 1869, Colonel Robert C. Brinkley opened a lavish hotel on the corner of Main and Monroe Streets as part of the building reprocess. It boasted 75 accommodations with private baths, a ballroom, saloon, and lobby. Brinkley intended to name the grand structure after himself, but just as the hotel was about to open, he received word of the death of his dear friend, philanthropist George Peabody. (Peabody had specifically financed the development of a rail system from Memphis to Charleston). To honor his friend's memory and generosity, Brinkley christened the new business as “The Peabody Hotel.” Soon after it opened, Brinkley gave the hotel to his daughter, Anna Overton Brinkley, and her husband, Robert B. Snowden. Despite the change in ownership, it quickly became the most popular retreat in Memphis and even attracted many upscale clients from across the nation. Among the names featured in its guestbook included two U.S. Presidents—Andrew Johnson and William McKinley.

The original Peabody shutdown to make way for an upscale department store known as “Lowenstein’s” in 1923. But the owners endeavored to construct an even grander Peabody Hotel nearby. Selecting a plot of land on the corner of Second Street and Union Avenue, construction on the new building lasted for some two years. Renowned Chicago-based architect Walter W. Ahlschlager was subsequently hired to spearhead the project, who designed a brilliant, 12-story skyscraper that displayed some of the finest Italian Renaissance Revival-style architecture in the whole country. Ownership spared no expense, either, spending some $5 million to raise the entire edifice. When the new Peabody Hotel finally debuted in 1925, it immediately reestablished itself as one of the grandest places to stay the city. Like its predecessor, the new Peabody featured 625 guestrooms that offered nothing except the finest in contemporary comfort. Several of its venues—including the Night Cap Club, the Venetian Dining Room, and the Marine Roof—also emerged as important cultural institutions for Memphians of all walks of life. In fact, dozens of celebrated entertainers frequently performed inside the hotel’s stunning facilities, such as Benny Goodman, Dorothy Lamour, Les Brown, Tommy Dorsey, Harry James, Furry Lewis, and the Andrew Sisters. The musical acts were so admired that CBS radio began broadcasting them nationwide in 1937.

The Peabody Hotel continued to serve as an important gathering place throughout the next few decades, gaining a national reputation for its world-class hospitality and classical elegance. The Plantation Roof and adjoining Skyway Room (the former Marine Roof) remained the center for the city’s vibrant nightlife by the middle of the century. But in the 1970s, Memphis experienced a prolonged period of urban decay. A series of small structural accidents and ownership changes—coupled with declining occupancy and downtown business—forced The Peabody Hotel to close for good. Facing an uncertain future, The Peabody Hotel was fortunately saved by the Belz family in 1975. They subsequently embarked upon a six-year, $25-million renovation that sought to resurrect the hotel’s historic grandeur. Thankfully, The Peabody Hotel reopened in 1981 and quickly regained its status as the "South's Grand Hotel." Now known as “The Peabody Memphis,” it continues to be one of the best hotels to visit throughout the American South. It still attracts many illustrious guests, as well, including powerful dignitaries, important business leaders, and Hollywood superstars. In fact, The Peabody was even featured in the 1993 thriller, The Firm. It’s famous “Peabody Duck March” has also continuously captivated the imagination of numerous guests ever since its creation during the Great Depression. Few other destinations today can truly rival the historical magnificence of The Peabody Memphis.

-

About the Location +

Occupying a bluff high above the Mississippi River, the site of present-day Memphis has long been inhabited for centuries. Generations of Native Americans once lived at the bluff for thousands of years, building a complex network of earthen burial mounds and ceremonial temples nearby. Despite the many different tribes that frequented the area, the Chickasaw eventually called the region home by the time the first Europeans arrived in the 16th and 17th centuries. In fact, one of the first people to come into contact with the local Chickasaw was explorer Hernando de Soto and French fur trader René-Robert Cavelier. The Spanish evenutally established a rudimentary fort atop the bluffs called “San Fernando de las Barrancas,” which attracted all kinds of frontiersmen over the next several decades. But the Spanish only controlled the bluffs for just a short period, dismantling it when the Americans acquired the region via Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795. Nevertheless, the first real permanent settlement created by Euro-American settlers emerged in the early 19th century. An American entrepreneur named John Overton purchased the rights to settle the area from another speculator called John Rice. Two other enterprising individuals, James Winchester and future U.S. President Andrew Jackson, decided to invest, and the three founded the city of Memphis around the bluff in 1819. (The name “Memphis” was an homage to the ancient Egyptian capital.)

Despite its proximity to the Mississippi River, Memphis grew slowly during the first few years of its existence. Disease, outlaws, and its relative remoteness discouraged its settlement for a while. But the city’s fortunes changed significantly in the 1840s, when steamboats became ubiquitous along the riverfront. It soon emerged as a popular port on the Mississippi, leading to its rapid growth in a matter of years. Three prominent railroads arrived shortly thereafter, using Memphis as a central terminal linking together cities in places as far away as South Carolina and Ohio. Memphis’ transformation into a prominent transportation hub caused its population to swell exponentially. In fact, Memphis grew faster than any other city in the United States at the time! Among the largest groups of people to settle in the city were Irish and German immigrants, who worked in jobs ranging from construction to shipping. But Memphis also saw an explosion of its African American community, many of whom were unfortunately enslaved. Most arrived into the city by way of the domestic slave trade, in which Memphis played an integral role before the American Civil War. Most urban blacks worked as domestic servants, although a sizeable number filled a number trades, too.

Memphis’ devotion to slavery eventually led its white population to wholeheartedly support the Confederacy. Many men volunteered for armed service, while the city’s industries started supporting the rebel war effort. But its allegiance came at a price, though, as its proximity to Union lines made it a military target early in the war. The Confederate defeat at Shiloh in 1862 incited a panic throughout Memphis, causing most of the white residents to flee further south. The federal navy arrived in their wake, subjecting its remaining citizens to an hour-and-a-half long siege later that June. Memphis subsequently remained under Union occupation for the rest of the conflict, although Confederate raiders led by Nathan Bedford Forest tried to wrestle control away in 1864. The large Union garrison also attracted some 15,000 African American refugees to settle in Memphis. The presence of so many recently freed slaves created a tumultuous social situation, especially after many of the former white residents returned upon the war’s conclusion. This tension eventually erupted into a calamitous race riot in 1866 that saw the black community attacked continuously for several days. Memphis further suffered from new outbreaks of disease during the 1870s, specifically endemic cases of yellow fever. Furthermore, the American Civil War had greatly destabilized Memphis’ economy, making its postwar reconstruction all the more difficult.

Memphis did not recover economically until the 1890s, as new industries specializing in cotton and hardwood byproducts opened across the city. Technologically advanced utilities also debuted, giving it a more modern character. Electricity, trolleys, and sanitation facilities all became common sights in Memphis. By the beginning of the 20th century, the municipality had reestablished itself as one of the South’s leading metropolises. One of the many interesting cultural developments that coincided with the city’s rebirth was its music. Many famous American songwriters got their start in the city, like Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Muddy Waters, and the iconic Elvis Presley. Most of those individuals would later move to other areas and share their music with their new communities. But perhaps the greatest musical development was the formation of the Memphis blues. Established by musicians such as Furry Lewis, and Sleepy John Estes, and Memphis Minnie, the genre was a version of the historic Delta Blues tradition. Memphis blues became immensely popular with all kinds of local performance halls and social clubs in West Memphis, which showcased the style regularly. Soon enough, some of the most celebrated American musicians had made a name for themselves while playing Memphis blues, such as Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King. Some of those artists even recorded exclusively with the great independent music label, Sun Records.

Race relations were still tenuous in Memphis in spite of its newfound prosperity, especially when African Americans began challenging the practice of segregation in the 1950s and 1960s. Memphis quickly became one of the focal points for the Civil Rights Movement, as the local black population started demanding full politician participation and equality before the law. At first, the municipal government accommodated a policy of gradual cooperation until intensified anti-segregation sentiment swept across the city. In the face of such resistance, black activists and their allies planned bolder protests that culminated with the Memphis Sanitation Strike of 1968. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. eventually arrived to lend his support, eventually giving his famous “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech before numerous followers. Unfortunately, an assassin shot Dr. King dead outside of his guestroom at the Lorraine Motel. Memphis has since reemerged stronger than ever, entering into the 21st century as one of America’s most cultural vibrant communities. Memphis is the site for many fascinating attractions, like the Belz Museum of Asian & Judaic Art, the Mississippi River Museum, and the National Civil Rights Museum (the former Lorraine Motel). Music continues to be heavily connected with the city’s contemporary identity, as many live venues still host shows in the Beale Street Entertainment District. Visitors can further explore the city’s special relationship with music today by visiting such destinations like the Memphis Rock ‘N’ Roll Soul Museum, the STAX Museum of the American Soul, and Sun Studio. Memphis is even home to Graceland, a National Historic Landmark that was once Elvis Presley’s former estate!

-

About the Architecture +

The current iteration of The Peabody Memphis was constructed at the height of the Roaring Twenties by renowned Chicago-based architect Walter W. Ahlschlager. A graduate of such prestigious schools like the Art Institute of Chicago, Ahlschlager created many beautiful buildings throughout his career, like Beacon Theater, the Mercantile National Bank Building, and Carew Tower. (Carew Tower is home to another member of Historic Hotels of America, the Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza.) The Peabody Memphis was among his first creations, which he designed as a spectacular 12-story skyscraper that overlooked the intersection of Second Street and Union Avenue. Built upon a U-shaped foundation, the first two floors featured a layer of grey terra cotta block that Ahlschlager topped with a buff terra cotta balustrade and decorative urns. The next nine levels contained large brown masonry, while the tenth story possessed a crown of terra cotta cornices and a few additional ornamental urns.

Five brilliant metal entrance foyers resided on the ground level, which displayed their own unique set of Italian-inspired travertine. Ahlschlager led each entryway directly into the hotel’s ornate lobby and its beautiful polychrome wood-beamed ceiling and colorful glass skylights. Terrazzo marble flooring proliferated throughout the space, graced by the presence of 16 marvelous square columns. The columns themselves were incredibly gorgeous, as Ahlschlager faced each one with rose St. Genevieve marble. A fountain dominated the center of the lobby that Italian artisans carved from a single block of white travertine marble. Its bowl also featured four cupids sitting astride dolphins, surrounded by a low octagonal curb of black and gold stonework. Many more outstanding facilities were located directly off of the lobby, too, such as the two-story Tea Room, the Continental Ballroom, and two magnificent dining spaces—the Venetian and Georgian rooms. Ahlschlager even designed every single one of the new 625 guestrooms to contain nothing but the finest amenities of the age.

Ahlschlager mainly used Italian Renaissance Revival style as the source of his inspiration. Italian Renaissance Revival architecture itself is a subset of a much large group of styles known simply as “Renaissance Revival,” which is among the most ubiquitous in America. Sometimes referred to as “Neo-Renaissance,” Renaissance Revival architecture is a group of architecture revival styles that originally date back to the 19th century. Neither Grecian nor Gothic in appearance, Renaissance Revival-style architecture drew inspiration from a wide range of structural motifs found throughout Early Modern Western Europe. Architects in France and Italy were the first to embrace the artistic movement, who saw the architectural forms of the European Renaissance as an opportunity to reinvigorate a sense of civic pride throughout their communities.

Those intellectuals incorporated the colonnades and low-pitched roofs of Renaissance-era buildings, with the characteristics of Mannerist and Baroque-themed architecture. Perhaps the greatest structural component to a Renaissance Revival-style building involved the installation of a grand staircase in a vein similar to those located at the Château de Blois and the Château de Chambord in France. This particular feature served as a central focal point for the design, often directing guests to a magnificent lobby or exterior courtyard. Yet, the nebulous nature of Renaissance Revival architecture meant that its appearance varied widely across Europe and North America. Many architects left their own mark upon any structure designed with Renaissance Revival-style design aesthetics, including Walter W. Ahlschlager. Historians, thus, often find it difficult to provide a specific definition for the architectural movement, yet acknowledge its inherent beauty, nonetheless.

-

Famous Historic Events +

Peabody Duck March (1933): Known the world over, the celebrated “Peabody Duck March” has captivated audiences for close to a century. In 1933, General Manager Frank Schutt first began the famous “Peabody Duck March.” Upon his return from a weekend-long hunting trip in Arkansas, Schutt and a few friends decided to leave three of their live English call ducks in the hotel fountain. Despite it being a joke, the hotel patrons loved watching the ducks swim around for hours. Inspired, Schutt left the ducks at the hotel, thus, giving birth to the tradition! Then in 1940, A bellman named Edward Pembroke volunteered to care for the Peabody Ducks. Hotel ownership subsequently bestowed the title of “Duckmaster” onto Pembroke, which he retained for the next five decades. He managed to teach the ducks how to march into the hotel lobby’s fountain with techniques he knew from his time as a circus animal trainer. By this point, the original call ducks had been replaced by five new birds—one drake and four female Mallards.

The Peabody Memphis has since featured this combination of ducks well into the present. The ducks continue to march down from the rooftop “Duck Palace,” where they head straight for the hotel fountain at 11:00 AM every morning. The ducks then turn around back to their pen at 5:00 PM. All the while, they walk toward the center of the lobby on a red carpet to a prerecording of John Phillip Sousa’s “King Cotton March.” Over the years, the Peabody Ducks have been featured on many television shows, such as Sesame Street, Coach, The Opera Winfrey Show, and The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Carson. The position of “Duckmaster” has also been an honorary title on a few occasions, especially in the aftermath of Pembroke’s retirement in 1991. Among the famous individuals to temporarily hold the tile are Joan Collins, Patrick Swayze, Oprah Winfrey, and President Jimmy Carter.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Tommy Johnson, blues guitarist known for his iconic falsetto voice and guitar playing style.

Furry Lewis, country blues guitarist remembered for helping establish the modern genre in the 1920s.

Harry James, big band leader known for working alongside the likes of Frank Sinatra, Benny Goodman, and Louie Bellson.

Benny Goodman, jazz clarinetist and band leader remembered to history as the “King of Swing.”

Tommy Dorsey, jazz musician known for such songs like “Opus One,” “Song of India,” and “I’ll Never Smile Again.”

Dorothy Lamour, singer and actress best remembered for appearing in the Road to… film series.

Andrew Sisters, close harmony singing group consisting of LaVerne Sophia, Maxene Anglyn, and Patricia “Pattie” May.

Les Brown, big band leader known for his group, Les Brown and His Band Renown.

Robert E. Lee, American Civil War General who led the Army of Northern Virginia.

Jefferson Davis, Senator from Mississippi and only President of the Confederate States of America.

Andrew Johnson, 17th President of the United States (1865 – 1869)

William McKinley, 25th President of the United States (1897 – 1901)

Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States (1977 – 1981)

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

The Firm (1993)

Guest Historian Series

Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 185;

Hotel History: The Peabody (1869), Memphis, Tennessee

by Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Following the Civil War, Memphis began the process of rebuilding. In 1869, Colonel Robert C. Brinkley opened a 75-room hotel which contained private baths, ballroom, saloon and lobby. Brinkley planned to name the hotel after himself but when he learned that his dear friend, philanthropist George Peabody, had died, he christened it The Peabody. Its lobby was soon filled with Memphis business and society leaders as well as plantation owners and riverboat gamblers. Presidents Andrew Johnson and William McKinley, Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee, Nathan Bedford Forrest and Jubal Early were guests. Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy, lived there in 1870 when he was president of a Memphis-based insurance company. After 57 years, the original Peabody was demolished to make way for a department store. It was replaced in 1926 by a new 12-story Peabody with elegant public rooms, ornate hand-painted beamed ceilings and duplex townhouse suites. It was built on the site of the Fransioli Hotel and was designed by the famous Chicago architect Walter W. Ahlschlager. He also designed the Roxy Theatre and the Beacon Hotel and Theater in New York; the Sheridan Plaza and Sovereign Hotels in Chicago; the Carew Tower in Cincinnati, the Medinah Athletic Club in Chicago, etc.

In 1935, historian David Cohn wrote:

- “The Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg. The Peabody is the Paris Ritz, the Cairo Shepheard's, the London Savoy of this section. If you stand near its fountain in the middle of the lobby, where ducks waddle and turtles drowse, ultimately you will see everybody who is anybody in the Delta.”

In 1932, general manager Frank Schutt and friend Chip Barwick returned from a hunting trip and decided to let their live duck decoys take a swim in the hotel's lobby fountain. This led to the creation of the March of the Peabody Ducks, a cherished Memphis tradition and an extraordinary public relations benefit to the Peabody. The world-famous March takes place daily at 11AM and 5PM with great fanfare. The guests love the idea and, since then, five Mallard ducks (one drake and four hens) have played in the fountain every day. Over the years, the Peabody Ducks have gained celebrity status with television appearances on the Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson, the Oprah Winfrey Show and Sesame Street. The custom of keeping ducks in the lobby fountain may date back even further than the 1930s. A pre-1915 postcard shows ducks playing in the fountain.

In 1940, bellman Edward Pembroke volunteered to care for the ducks. Pembroke was given the position of “Duckmaster” and served in that position until 1991. As a former circus animal trainer, he taught the ducks to march into the hotel lobby, which started the famous Peabody Duck March. Every day at 11AM, the Peabody Ducks are escorted from their penthouse home, on the Plantation Roof, to the lobby via elevator. The ducks, accompanied by the King Cotton March by John Philip Sousa, then proceed across a red carpet to the hotel fountain, made of a solid block of Italian travertine marble. The ducks are then ceremoniously led back to their penthouse at 5 PM.

In the 1950s, the Peabody suffered as a casualty of the declining fortunes of downtown Memphis. The Sheraton Corporation tried to revive the hotel in 1968 as the Sheraton-Peabody Hotel, the same year that Martin Luther King Jr. was shot to death while standing on the balcony of a small motel less than a mile south of the Peabody. His assassination and the subsequent riots accelerated the flight of white families and businesses. The hotel struggled to stay open for another seven years before it declared bankruptcy and closed in 1975. The destination was bought at a foreclosure sale by the Belz family who spent upwards of $25 million to renovate and restore the hotel. The grand reopening of the Peabody in 1981 was credited as the inspiration for the downtown revitalization of Memphis that followed. The Peabody's success has been the catalyst in the redevelopment of other downtown properties including two nearby hotels.

The Skyway Room on the Peabody roof was refurbished and, with the adjoining open-air Plantation Roof, are the scene of pop and rock concerts. In the 1930s and 40s, Benny Goodman, Harry James, the Andrews Sisters and Tommy Dorsey performed here. The Peabody was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and is a member of Historic Hotels of America.

*excerpted from his book Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi

*****

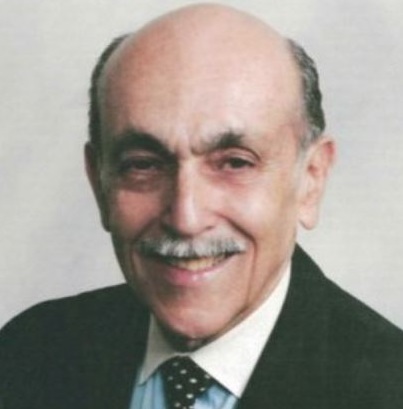

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.