Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

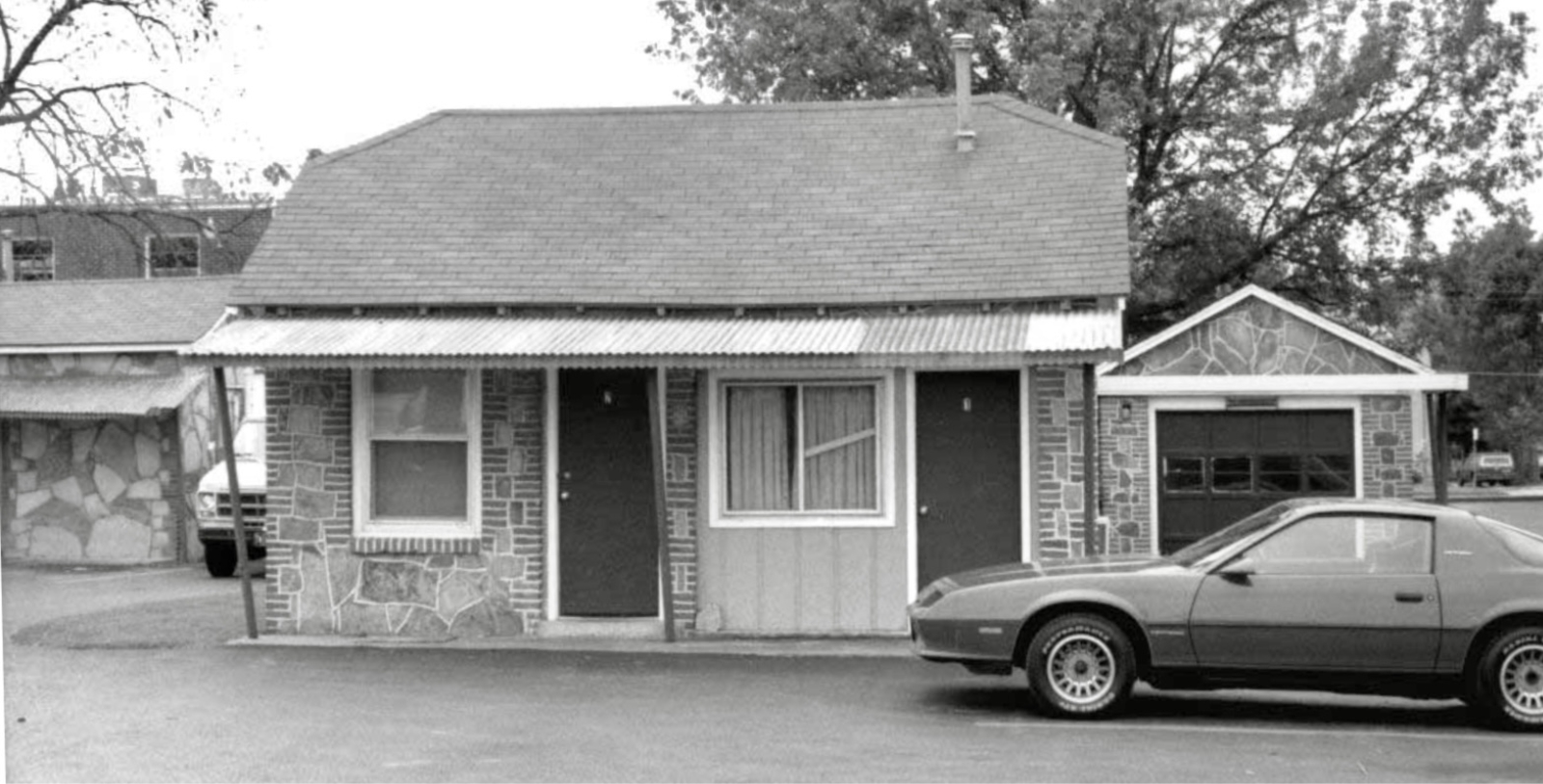

Discover Rockwood Motor Court, which is among the last surviving motor lodges still in operation along the legendary Route 66.

Rockwood Motor Court is one of the most historic destinations still in operation along the iconic Route 66. Its story is closely intertwined with the rise of automobile tourism, the evolution of roadside architecture, and the cultural significance of Route 66 as the “Main Street of America.” More specifically, the 1920s marked a transformative era for transportation in the United States. The automobile was no longer a luxury—it was increasingly becoming a necessity. As cars were manufactured to be more affordable, Americans themselves began to explore the country in ways that were previously unimaginable. In 1926, the federal government thus established Route 66—a 2,448-mile highway stretching from the plains of Illinois to the beaches of California. Springfield, Missouri, would go on to play a pivotal role in its formation, as officials intended to use the city as the central hub for the entire route! Just three years later, as the “Mother Road” itself was built, the Rockwood Motor Court opened to serve eager motorists navigating their way down the nascent thoroughfare. Located on St. Louis Street, which was then part of the original Route 66 alignment through Springfield, the motor lodge was ideally positioned to cater to the growing frequency of drivers heading west in search of opportunity, adventure, and even escape. The person responsible for its creation was local entrepreneur Deverne Ruckman, who originally founded the site as a tourist camp. She subsequently presided over the motel’s detailed construction, installing gorgeous stucco walls and a distinctive red roof on the main building—as well as rustic guest cabins—that all exuded a sense of charm.

Unlike the large hotels found in urban centers, motor lodges like the Rockwood Motor Court were designed for convenience. For instance, guests could park their vehicles directly in the private garage next to their cabins, which was a revolutionary concept at the time. Each unit at the Rockwood Motor Court featured comfortable accommodations as well, including private bathrooms, clean linens, and often a kitchenette. These amenities made it a favorite spot for families that preferred the exclusivity and affordability that traditional hotels could not offer. But the Rockwood Motor Court was particularly special in that its handful of cozy guestrooms were housed inside six distinctive cabins, granting an extra level of privacy not typically seen at other motor lodges. (Interestingly, guests would pay 50 cents a night to pitch a tent in the front yard if no cottages were available at the height of the Great Depression.) Nevertheless, as Route 66 gained popularity throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Rockwood Motor Court thrived in turn. Thousands of people accessed the road to go on vacation, representing the expanding size of the American middle class. The highway soon adopted further noteworthy functions, too, becoming an important lifeline for migrants fleeing the Dust Bowl and soldiers heading off to fight during World War II. As a result, Rockwood Motor Court started to morph into something more than a mere place to sleep—the structure was soon emblematic of the greater zeitgeist that was then defining America! Unfortunately for the Rockwood Motor Court (and sites like it), the gradual debut of the Interstate Highway System began to endanger the cross-country travel occurring on Route 66. Indeed, the novel road network eventually bypassed Springfield completely, diverting traffic away with increasing numbers.

Similar developments transpired across the nation, ultimately forcing many motor courts to permanently close for good. But the Rockwood Motor Court survived, thanks to its loyal clientele, retro character, and convenient proximity to downtown Springfield. In consequence, the historic motor court was among the last attractions of its kind to embody the rich heritage of Route 66 and its impact on American life. Then in the early 21st century, Route 66 underwent an unexpected renaissance. Historians, preservationists, and nostalgic travelers resumed recognizing the historical value of the highway, prompting various efforts to protect its legacy. Springfield especially embraced its Route 66 connections, as its residents quickly went about renovating multiple landmarks related to the road. Rockwood Motor Court emerged as a community focal point for the revival. The new owners proceeded to start numerous preservation projects, such as the restoration of its neon signage, the refurbishment of its vintage décor, and the enhancement of its historic interpretation on site. Now once more a revered vacation hotspot, Rockwood Motor Court has since come to symbolize the very essence of Route 66. Both were born amid the optimism of the 1920s, weathered the storms of global tumult, and faced the existential threat of modernization. Yet they each have managed to endure, posing as reminders that the idea of the open road continues to hold an alluring appeal in the national collective imagination. As travelers today seek authentic experiences rooted deeply in history, Rockwood Motor Court can truly provide a rare opportunity to rediscover the spirit of mid-century Americana.

-

About the Location +

Known as the "Queen City of the Ozarks," Springfield, Missouri, is a city steeped in history. The community’s amazing story begins long before its official founding, with indigenous tribes like the Osage, Delaware, and Kickapoo building a network of interconnected villages across the region generations ago. Euro-American pioneers started inhabiting the area during the early 19th century, establishing a small settlement at the site of present-day Springfield. Dozens more families constructed farms around the new village, including the soon-to-be legendary Campbell family. More specifically, brothers John and Madison Campbell selected a plot of land near a spring, notably staking their claim by carving their initials into a neighboring ash tree. Local historians have considered this act to be the symbolic creation of Springfield, as their homestead became the launchpad upon which the future city would emerge over the following decades. Slowly but surely, the population gradually rose throughout the century, as travelers making their way west discovered great economic opportunities in the town.T he community was able to receive a municipal charter from the Missouri state government in 1838, adopting the name “Springfield” permanently in the process. Because of its location near key routes through the Ozarks, Springfield held significant cultural importance for the people of southwestern Missouri.

This prominence even made the city a major military target early during the American Civil War, as Union and Confederate forces came to wage a pitched battle close to a nearby creek. In 1861, each side was furiously trying to control Missouri, a border state without clear loyalties at the time. Union and Confederate armies under Nathaniel Lyon and Sterling Price, respectively, had skirmished across the state that summer, their fighting drifting south toward the vital crossroads at Springfield. On August 10, Lyon staged a surprise attack on Price, whose men were encamped along a body of water outside the city called “Wilson’s Creek.” The ensuing combat was the first major battle to occur west of the Mississippi River, as well as the first one to see a Union general—Lyon—killed in action. Though the Confederates won the engagement, they nonetheless withdrew, and Missouri fell under Union control in consequence. However, Springfield remained a strategic asset to both armies, with the Confederates launching a spirited counterattack two years later. Union troops successfully defended the area though, resulting in its firm occupation by Union forces for the remainder of the conflict. Then in the wake of the American Civil War, Springfield returned as a launchpad for travel further west into the frontier. As a result, the city gradually adopted a character reminiscent of the Old American West. In July 1865, for instance, Springfield’s main square became the site of the first recorded quick-draw shootout in the country. The event foreshadowed a host of similar instances, including the infamous dual that eventually made “Wild Bill” Hickok a household name.

Despite the rambunctious nature of the city, it continued to grow due to its status as a regional transportation center. The arrival of the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway was the highlight of this trend, as the access to the line spurred a wave of prolonged urbanization that completely altered Springfield’s appearance! This incredible period of prosperity lasted well into the 20th century, particularly once the iconic highway Route 66 debuted in downtown Springfield during the 1920s. The road went on to make Springfield one of the most prominent holiday destinations in the entire region, granting visiting tourists unprecedented access to natural wonders like the Ozarks. Although no longer a rugged western town, Springfield has remained a culturally fascinating place to experience. Not only has the city endured as a popular destination among travelers interested in exploring the mountain ranges nearby, but it has also enticed them with its array of fascinating attractions. Indeed, Springfield is host to renowned landmarks like the Route 66 Car Museum, the Springfield Art Museum, and Johnny Morris' Wonders of Wildlife National Museum and Aquarium. Additional destinations are located just beyond the city limits, including the Fantastic Caverns and the Wilson's Creek National Battlefield site. Even other exciting communities, such as the famed entertainment hub of Branson, are just a short drive away from the heart of Springfield!

-

About the Architecture +

Rockwood Motor Court possesses a unique architectural style that can best be described as “eclectic.” Dating to the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, historians today consider “eclecticism” to be part of a much larger movement to fuse together a variety of historical designs. Earlier in the 1800s, architects—particularly those in Europe—decided to rely upon their own loose interpretations of historical architecture whenever they attempted to replicate it. Such a practice appeared within styles like Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Second Empire architecture. But at the height of the Gilded Age, those architects decided to use historic architecture more literally when developing a building. A few architects went a step further by combining certain historical styles together to achieve something uniquely beautiful. And in some cases, those individuals felt inspired to add a new historical form onto a building that they were renovating—just like the Boar's Head Resort. Nevertheless, the architects felt that joining such architectural forms together would give them a new avenue of expression that they otherwise did not have at the time. But they even believed that they had stayed true to the earlier forms, so long as their designs perfectly replicated whatever it was, they wanted to mimic.

In Europe, this approach first appeared as a rehash of Gothic Revival-style known as “Collegiate Gothic.” The European architects then used such a mentality to influence the unfolding philosophies of both the Beaux-Arts school of design, as well as the emerging Renaissance Revival-style. Many architects in America followed suit, the most notable of which being Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim. The American architects who embraced “eclecticism” were at first interested in the country’s colonial architecture. Much of the desire to return to the period was born from the revived interest in American culture brought on by the Centennial Exposition of 1876. More specifically, pride in preserving the nation’s heritage inspired the architects to perfect the design principles of their colonial forebearers in new and intriguing ways. This interest gradually splintered into other revival styles though, like Spanish Colonial and Tudor Revival. Some Americans even infused the approach with the popular Beaux-Arts aesthetics of France, such as Hunt and McKim. However, the birth of Modernism in the 1920s and 1930s eventually ended the worldwide love affair with “eclecticism,” for architects throughout the West becoming more enchanted with the ideas of modernity, technology, and progress.

-

Famous Historic Events +

Route 66

Few roads in the United States have captured the imagination and spirit of the nation quite like Route 66. Stretching for approximately 2,450 miles in length, Route 66 is more than just a highway—it acts as a symbol of freedom, migration, and the American dream. The very idea for Route 66 emerged at a time of rapid automobile expansion during the early 20th century. As cars became more accessible, Americans demanded better roads. In response, Congress passed the Federal Aid Highway Act in 1921, which laid out the groundwork for a sprawling highway system that could meet those expectations. Rather than being built from scratch, Route 66 instead functioned as a patchwork of existing local, state, and national roads. It followed paths that had been used for centuries, like Native American trails, Spanish colonial paths, and railroad lines. Yet the route managed to reach major urban centers, including Chicago, St. Louis, Oklahoma City, and Los Angeles. Work on the actual development of the highway did not fully begin until 1925, with engineers connecting the various stretches together via dirt thoroughfares. (For reference, Springfield, Missouri, saw Route 66 arrive a few years later.) But thanks to New Deal-era federal funding, the entire expanse of Route 66 was finally paved near the end of the 1930s. It was not long before Route 66 had thus become an important institution for thousands of people throughout the country.During the Dust Bowl, Route 66 was a lifeline for displaced families who migrated westward in hopes of finding work. (This harrowing experience was immortalized in John Steinbeck’s classic novel The Grapes of Wrath, where he famously dubbed Route 66 the "Mother Road.”) Then as the nation mobilized for World War II, Route 66 played a strategic role in transporting troops to the West Coast. After the conflict though, Route 66 truly entered its golden age. With automobile ownership skyrocketing, families took the road for thrilling vacations. The number of mom-and-pop businesses on the highway soon multiplied as a result, including motels akin to the Rockwood Motor Court in Springfield, Missouri. These establishments not only provided essential services but contributed to the unique roadside culture that eventually defined Route 66. Indeed, Route 66 became synonymous with the American road trip with many distinctive kinds of pop cultural productions reinforcing the perception. Musician Bobby Troup wrote the incredibly popular song “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66” that artists like Nat King Cole, Chuck Berry, and The Rolling Stones later recorded. Renowned Hollywood icons Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper captured the road’s relationship to the mid-century countercultural movement in their classic film Easy Rider. CBS even aired a television series called Route 66, which portrayed the highway as an incredible place of adventure and self-discovery.

Route 66 was not built to handle the increasing volume of post-war traffic. To address the problem, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, which initiated the construction of the modern Interstate Highway System. Although the effects of these new roads were not felt immediately, they would come to displace Route 66 given their faster and safer characteristics. Observing the decline of the once great thoroughfare, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials voted to ultimately decommission Route 66 in 1985. The decision subsequently devastated many communities that had relied on the highway for commerce, with some turning into ghost towns. However, Congress eventually recognized the cultural significance of Route 66 and created the Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program to help revitalize the legendary road. Historic preservationists have since worked tirelessly to protect the highway’s legacy, with many distinctive historic sites having been renovated to reflect their former glory. More recently, the National Trust for Historic Preservation provided grants to aid in the ongoing restoration of Route 66, while highlighting hidden gems to explore along the route. Route 66 remains a powerful symbol of America’s journey through the 20th century. From its humble beginnings as a patchwork of rural streets to its rise as a national cultural icon, the site continues to inspire travelers, historians, and dreamers alike to this very day.

-

Film, TV and Media Connections +

Dust to Malibu (2024) .