Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover The Mills House, Curio Collection by Hilton, which once hosted President Theodore Roosevelt when he traveled to Charleston to experience the famed South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition.

The Mills House, Curio Collection by Hilton, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2024, dates back to 1852.

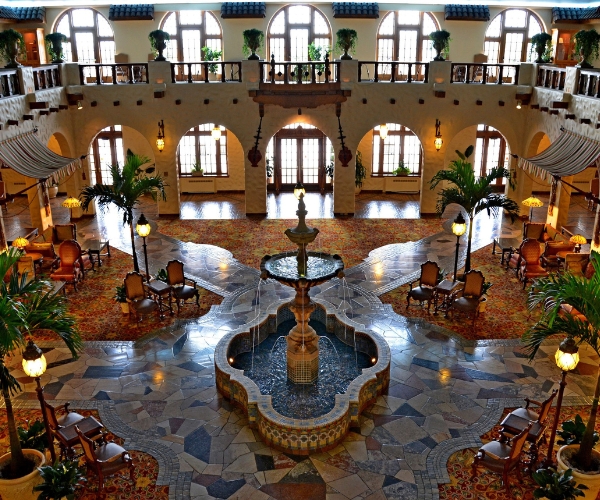

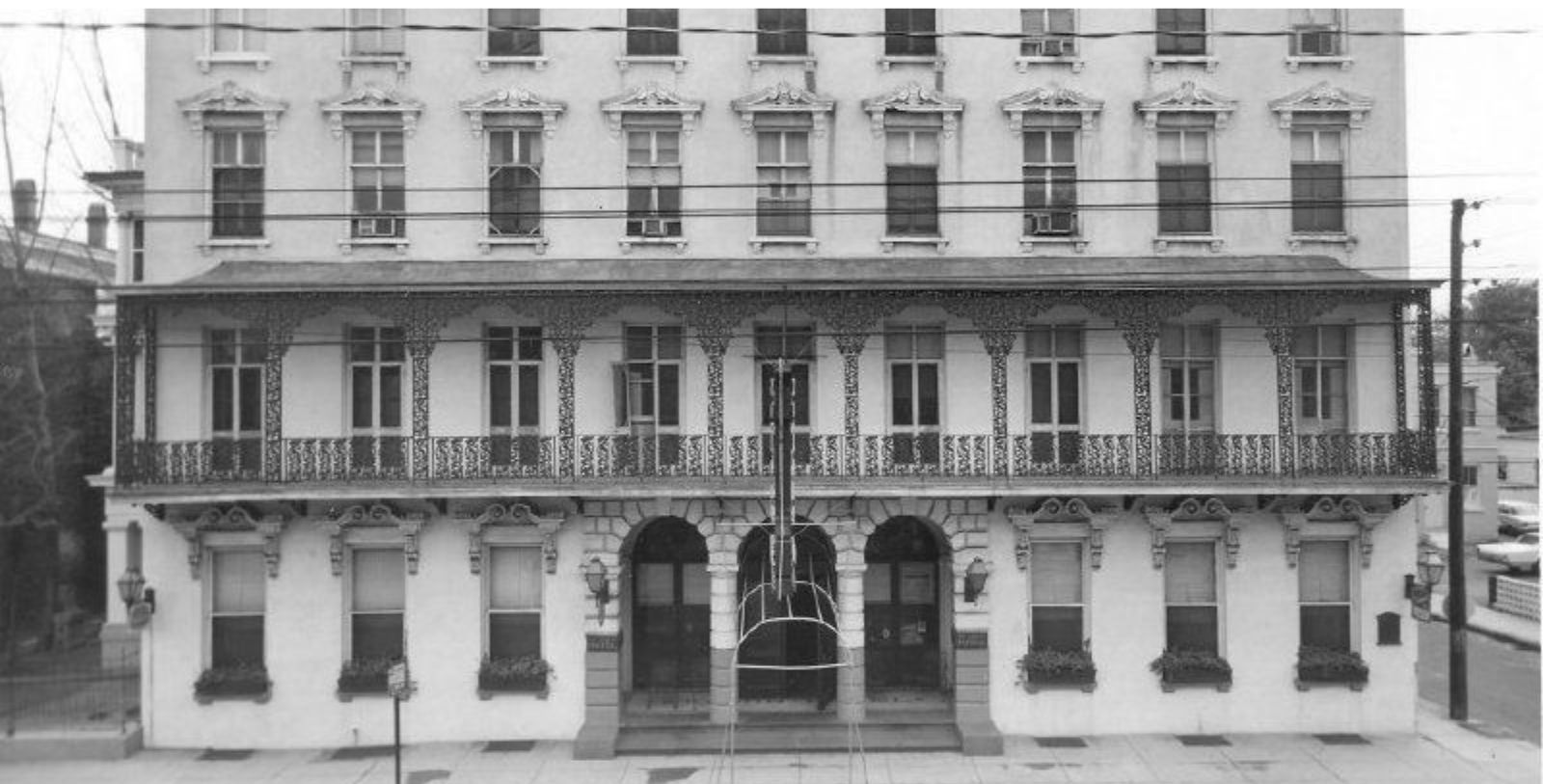

VIEW TIMELINEIn 1836, an enterprising businessman named Otis Mills immigrated south from his native Massachusetts to the bustling port of Charleston, South Carolina. Although the exact reasons for his move are unclear, one can imagine the city’s lucrative maritime commerce as providing significant motivation. Nevertheless, Mills established a prosperous grain exporting company within months after his relocation. Now one of Charleston’s most successful entrepreneurs, Mills subsequently began to reinvest his wealth in various properties throughout the city. Among his real estate purchases was a desirable plot of land on the corner of Queen and Meeting streets, which featured a gorgeous manor once inhabited by the influential Grimké family. In fact, Mills had found the structure to be so extraordinary that he began arranging to transform the entire facility into an exclusive hotel. Despite his enthusiasm, Mills did not actually implement his plan until the beginning of the 1850s. To that end, Mills hired a renowned architect named John E. Earle to oversee the dramatic conversion of the former Grimké mansion. Earle in turn crafted a magnificent five-story hotel that displayed an ornate variety of beautiful Italianate-style motifs. Masterfully installed terracotta cornices resided under every window, while picturesque iron balconies anchored the front façade. A majestic arcade entrance also led to an interior floorplan richly ornamented with marble mantels and intricate ceiling moldings. Mills had Earle spare no expense, too, ultimately allowing him to spend some $200,000 to complete the project.

When the new “Mills House Hotel” finally opened in 1853, it quickly emerged as Charleston’s most popular holiday destination. Guests marveled at the building’s breathtaking appearance, commenting that it resembled a palatial Italian estate. But they also found the diverse cutting-edge amenities offered on-site to be equally remarkable, such as its indoor plumbing, steam heating, and network of mounted gaslights. The Mills House Hotel would thus remain a prestigious social gathering spot for the next several years, attracting illustrious travelers from across the country. Perhaps the hotel’s most impressive feat was that its popularity managed to endure in the face of the tremendous hardships that affected Charleston over the coming decade. Charleston itself specifically became a battlefield amid the American Civil War, with nearly all its city blocks destroyed by General William T. Sherman’s Union armies as they advanced deeper into the state. The Mills House Hotel nonetheless survived the ordeal, miraculously continuing to serve guests while the rest of Charleston smoldered. But the conflict eventually impacted Otis Mills himself, who felt compelled to sell his famed hotel as a way to support the local home front.

The business then proceeded to exchange hands frequently, before falling under the care of Cecilia Lawton in the early 20th century. She strove hard to maintain the building’s appeal, initiating her own series of extensive renovations that culminated with its renaming as the “St. John’s Hotel.” Lawton’s efforts proved fruitful for a time, even helping to secure the reservation of President Theodore Roosevelt when he visited the city to attend the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition in 1902. Unfortunately, the debut of newer venues nearby had severe repercussions for the business, which started struggling immensely to compete. As a result, the historic Mills House Hotel closed indefinitely around the middle of the century. Then in 1967, a group of preservation-minded businesspeople acquired the Mills House Hotel intent on restoring it back to its former glory. However, the team soon discovered that the structure had experienced too much irreparable neglect in the years leading up to their purchase. They instead opted to reconstruct the hotel right down to its original layout, going as far as to reincorporate any reuseable historical components within the new building. The group endeavored to faithfully resurrect the Mills House Hotel, employing dozens of engineers and artisans to carefully mirror the site’s original architectural design. Following three years of constant construction, the owners introduced the reborn Mills House Hotel to great local acclaim in 1970. Known as the “Mills House Charleston, Curio Collection by Hilton” today, this fantastic historic hotel has since resumed its place as one of Charleston’s best places to stay. A fair amount of the hotel’s present success is thanks to the dedication of current owner RLJ Lodging Trust, which has done much to preserve its legacy for future generations to appreciate.

-

About the Location +

Named after King Charles II of England, Charleston is among the most historic cities in the whole United States. The first settlers to establish the city arrived back in the mid-17th century, when the Lords Proprietors—the original officers for the unsettled Carolina territory—began moving colonists from Barbados and Bermuda to the area. The Lords Proprietors then selected a number of sites for settlement around the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper rivers, before finally finding success at a place called “Oyster Point” in 1672. Despite intending to develop the nascent community around a visionary plan known as the “Grand Model,” “Charles Towne”—as it was initially called—was never incorporated until the late 18th century. Nevertheless, life in early Charleston was incredibly tough, as the town was beset by hostile groups of French, Spanish, and Native American armies. Pirates posed a fundamental problem, too, who raided the coastline frequently. Edward Teach—remembered today as “Blackbeard”—was even among the pirates to harass Charleston regularly at the time. Furthermore, malaria and other tropical diseases took their toll on the English colonists, as did natural weather phenoms like hurricanes.

Growth only picked up once immigrant populations from Europe began expanding westward into the South Carolina interior. Their arrival also saw the city’s economic fortunes change significantly, as it rapidly emerged as a commercial port for the outlying farms that surrounded Charleston. Rice, indigo, and other cash crops were common exports transported through Charleston’s natural harbor, which helped make the city one of the most prosperous in the Thirteen Colonies. But the new maritime commerce had a considerable dark side, for the transatlantic slave trade had also played a role in Charleston’s rebirth. By the eve of the American Revolution, nearly half of the city’s population—some 11,000 people—were either enslaved Africans or their descendants. Still, Charleston’s size and prosperity as a port made it one of the largest cities in British America, as well as the principal point of entry for any person—free or enslaved—entering the South. Charleston remained a busy port even as Great Britain continuously targeted the city throughout the American Revolutionary War. The city itself was eventually captured after British general Sir Henry Clinton successfully subjected it to a prolonged siege in 1780.

In the wake of the American Revolution, cotton then emerged as the primary staple crop shipped through Charleston Harbor. But the number of slaves transported into the city increased dramatically, too. The local devotion to slavery made the city committed to the concept of southern secession—an idea that became reality when South Carolina’s state legislature voted to secede following Abraham Lincoln’s first election in 1860. Charleston soon found itself at the middle of the American Civil War as a result, with the first shots of the conflict fired right within its own borders. Rebel militia under the command of P.G.T. Beauregard had specifically bombarded the U.S. Army-occupied Fort Sumter shortly after Lincoln’s call for volunteers in April 1861. Four years of constant warfare came in the wake of the attack, which eventually destroyed much of Charleston and the rest of South Carolina. Charleston struggled to emerge from the conflict, as industrialists and other entrepreneurs chose to move their operations elsewhere.

However, in the early 20th century, Charleston underwent a cultural renaissance that sought to highlight the positive aspects of the city’s history and culture. New art and literature appeared throughout Charleston, while many historic structures were preserved for the first time. Race relations also began to improve, with local African Americans gradually gaining access to more rights and liberties by mid-century. Charleston now rates among America’s most diverse communities, as well as one of its most culturally vibrant. People today love traveling to the city to experience its many interesting historic sites, such as Fort Sumter, the Historic Charleston City Market, and Magnolia Plantation and Gardens. But visitors also adore the wealth of historical architecture that calls Charleston home, giving it an incredibly gorgeous landscape. Many of those aesthetics—ranging from Greek Revival to Federal—reside within famous neighborhoods like the renowned Charleston Historic District. In fact, the Charleston Historic District was even designated a U.S. National Landmark by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior in 1966!

-

About the Architecture +

When architect John E. Earle first designed The Mills House, Curio Collection by Hilton, he chose Italianate architecture as the main source of inspiration. One of the first examples of Renaissance Revival-style architecture, Italianate design principles themselves are some of the most historic ever used in the United States. Despite its popularity in the United States, it was originally conceived by a British architect named John Nash at the beginning of the 1800s. Inspired by the architectural motifs of 16th-century Italy, he constructed a brilliant Mediterranean-themed estate called “Cronkhill” in his native England. Nash had borrowed heavily from both Palladianism and Neoclassicism to design the building, both of which were derivatives of the Italian Renaissance art forms. Soon enough, many other architects began copying Nash’s style, using it to construct similar manors across the English countryside. However, the person responsible for popularizing the aesthetic the most was Sir Charles Barry, who had his own offshoot called “Barryesque.” By the middle of the century, this Italian Renaissance Revival-style architecture had spread to other places within the British Empire, as well as mainland Europe. It had even crossed the Atlantic during the 1830s, where it dominated the American architectural landscape for the next 50 years. Architect Alexander Jackson Davis promoted the style, using it to design such iconic structures as Blandwood and Winyah Park in New York. Although he was more widely known for his use of another Revival style—Neo Gothic—his work with Italianate helped cement it within the United States.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

- Elizabeth Taylor, actress known for her roles in Cleopatra and The Taming of the Shrew

- Paul Newman, actor known for his roles in such films like Cool Hand Luke, The Sting, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

- Joanne Woodward, actress best remembered for her role in the film, The Three Faces of Eve

- Tony Bennett, musician known for such hits as “Because of You,” “Rags to Riches,” and “I Left My Heart in San Francisco”

- Princess Caroline of Monaco

- Dick Cheney, 46th Vice President of the United States (2001 – 2009)

- Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States (1901 – 1909)

- Ronald Reagan, 40th President of the United States (1981 – 1989)

- George H.W. Bush, 41st President of the United States (1989 – 1993)

- Joe Biden, 46th President of the United States (2021 – present)