Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover The Georgian Terrace, which has been a place for experiencing arts and glamour in Atlanta since opening its doors in 1911.

The Georgian Terrace, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2001, dates back to 1911.

VIEW TIMELINE

The Georgian Terrace Hotel in Midtown Atlanta - History & Tour

Discover the history and heritage of Atlanta's modern classic hotel.

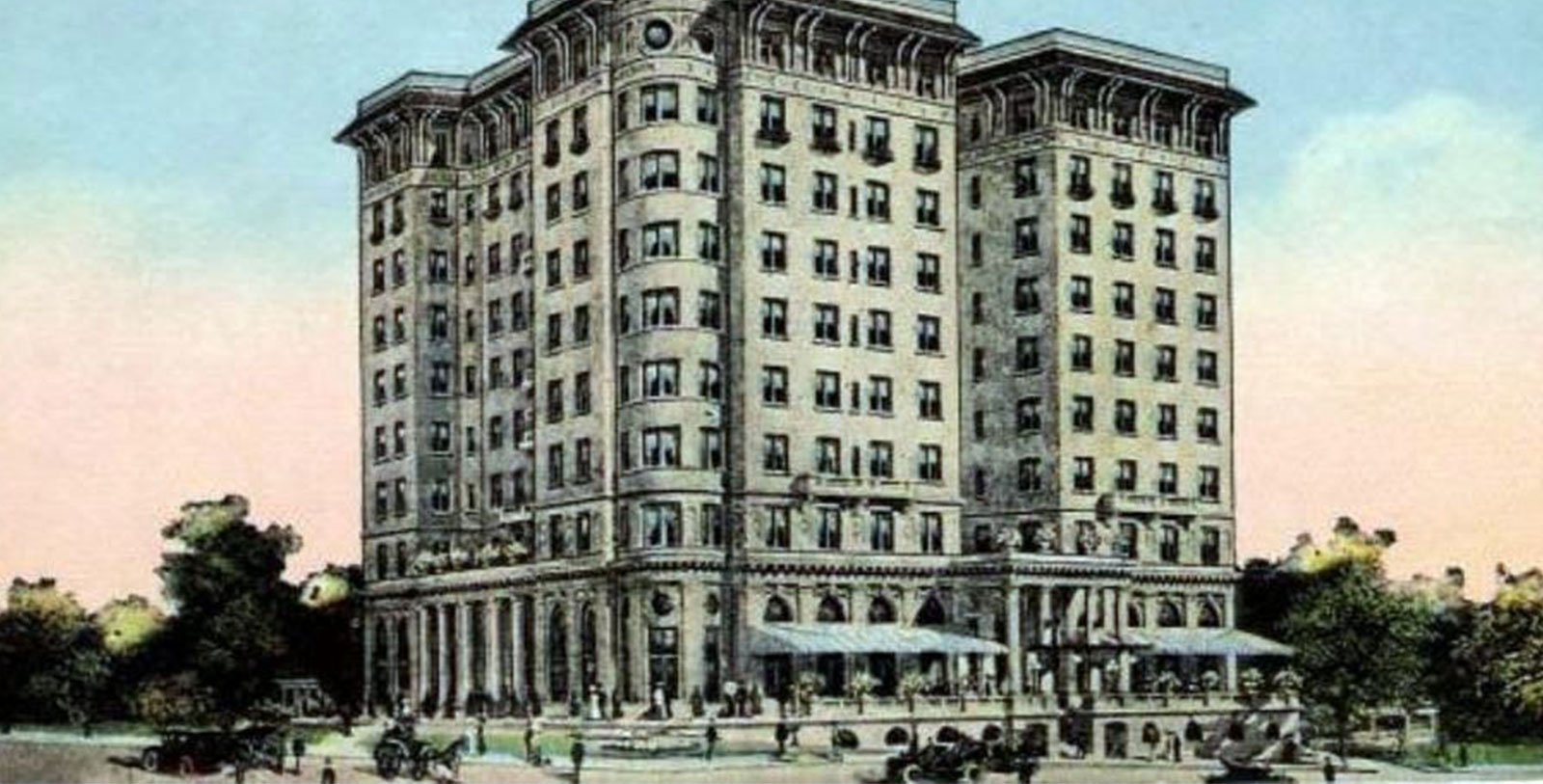

WATCH NOWA contributing structure within the Fox Theatre Historic District, The Georgian Terrace has stood as a cherished local landmark in Atlanta for more than a century. The history of this prestigious historic hotel is swept up in tales of romance and glamour. As one of the first hotels to be built outside of Atlanta's downtown business district, The Georgian Terrace cost a mere $500,000 and was constructed in a Beaux-Arts style by architect William Lee Stoddart. The concept of the hotel was based upon a Southern interpretation of a Parisian Grand Dame. Classic architectural details such as turreted corners, Palladian-style windows, decorative terra cotta, crystal chandeliers, and wrap-around terraces are featured throughout the building. The Georgian Terrace officially opened its doors in October of 1911 to much fanfare, which included a Spanish orchestra stationed in the Grand Ballroom. Thousands of guests from Atlanta and elsewhere attended the opening ceremonial festivities. Since that promising opening day, The Georgian Terrace has been a tremendous patron to the performing arts. Beginning in 1913, Italian tenor, Enrico Caruso, and the rest of the Metropolitan Opera, used the landmark Georgian Terrace as their home base for whenever they were in town performing their spring concert. Then five years later, Arthur Murray started teaching dance lessons in the Grand Ballroom, which eventually evolved into his franchise-branded studio business.

Soon enough, The Georgian Terrace had managed to build a prestigious reputation that was felt throughout the entire country. Many other illustrious guests began to arrive in great numbers, including the likes of Helen Keller, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tallulah Bankhead, Walt Disney, and Elvis Presley. A few U.S. Presidents have even spent time inside the hotel, including Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. In the 1970s, concert promoters Alex Cooley and Mark Golob, turned the Grand Ballroom into the “Electric Ballroom,” and introduced famous, modern acts, such as Billy Joel, Bruce Springsteen, Fleetwood Mac, Patti Smith, and the Ramones. But a decade later, The Georgian Terrace’s revenues had declined steadily and its doors were shuttered. The 1990s were the start of a new era for The Georgian Terrace, as it saw a brand-new 19-story wing developed. The hotel underwent major renovations in 2000 and 2009, restoring the luxurious character it possessed when it first opened a century ago. A member of Historic Hotels of America since 2001, The Georgian Terrace is truly among the best historic destinations in all of Georgia.

-

About the Location +

The Georgian Terrace is one of three major structures that constitute the Fox Theatre Historic District in Midtown Atlanta. The small neighborhood got its name from the historic Fox Theatre, which debuted around a decade after The Georgian Terrace first opened in 1911. Designed by Oliver Vinour, many throughout Atlanta believed the building to be among the most beautiful in the city. It displayed an interesting blend of Islamic and ancient Egyptian architecture, including a 4,665-seat auditorium that closely resembled an Arabic courtyard. The theater was originally planned to serve as a large temple for The Shiners, although they never fully occupied the location due to budgetary constraints. The organization eventually leased most of the structure to film tycoon William Fox, who subsequently transformed it into another one of his fabulous movie palaces. Fox then debuted his section of the building as the “Fox Theatre,” while The Shiners moved into a small wing set off to the side. Yet, Fox Theatre closed just weeks after opening in the fall of 1929. Ruined by the stock market crash, Fox declared bankruptcy just three years later. A local theatre company called “Lucas & Jenkins” quickly formed a partnership with Paramount Pictures to purchase Fox’s complex. The theater then showcased many unique movie premieres and emerged as one of the city’s greatest icons. At the same time, its gorgeous Egyptian Ballroom became one of the most popular social clubs in Atlanta. Despite a brief period of inactivity at the end of the 20th century, Fox Theatre is still very much active today. And while it is no longer an exclusive movie theater, it does host a number of exhilarating cultural and artistic events regularly.

Atlanta itself first came into existence in the late 1830s, when the Western and Atlantic Railroad selected the site of present-day Atlanta as the location for a train depot. Commissioned by the Georgia General Assembly, the railroad was intended to link the seaside city of Savannah further inland to the commercially important settlement of Chattanooga, Tennessee. As such, the depot would provide logistical support for all the trains that needed to traverse the Appalachian Mountains in northern Georgia. A small community quickly formed around the facility, which was originally known as both “Terminus” and “Marthasville” before becoming “Atlanta” during the 1840s. Traffic on the Western and Atlantic Railroad increased dramatically over the next two decades, inspiring several private companies to link their own routes through the fledgling city. A vibrant industrial economy quickly emerged alongside the railroads, too. By the time the American Civil War erupted, the city had grown into one of the most economically vibrant communities in the entire nation. Atlanta’s value as a transportation hub and manufacturing center had made it a strategic target for the Union, which sought to capture it as soon as possible. In 1864, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman finally achieved the elusive goal after a climatic, four-month-long siege known to history as the “Battle of Atlanta.” The city was subsequently desolated by both the Confederate and Union armies, as they both hoped to deprive the other of the area’s useful military assets. Atlanta’s capture was a significant boost to Northern morale, and even aided in President Abraham Lincoln’s reelection later that fall. Sherman himself then used Atlanta as his primary supply base amid his famous campaign remembered as the “March to the Sea.”

When the American Civil War finally concluded the following year, Atlanta was swiftly rebuilt by its inhabitants. But Atlanta quickly became politically important, as the state legislature decided to meet in the city to closely coordinate the rebuilding efforts across Georgia. Atlanta’s railroad network made communicating with those disparate communities incredibly easy. As such, the state administration decided to relocate the capital to Atlanta in 1868. With the city’s political and economic rebirth came a subsequent cultural renaissance that persisted well into the first decades of the 20th century. Atlanta expanded at an unprecedented rate, spurred on by countless new business that had opened within the its borders. Among the many enterprises to appear at the time was the nascent Coca-Cola Company in 1892. Yet, race relations remained a point of contention inside the city, which ultimately made Atlanta a hotbed for the Civil Rights Movement. Led by Atlanta-native Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the city’s civil rights activists began organizing a massive campaign of civil disobedience that struck at racial inequality on a national scale. Dr. King emerged as the most visible spokespeople for the movement alongside his Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In recognition of his legacy, Dr. King’s Ebenezer Baptist Church and his adjacent gravesite currently serve as the Martin Luther King, Jr., National Historic Site. Atlanta is now among the most historic destinations in the whole United States. From its fascinating Civil War-era history to its connections with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., few places can claim the heritage that Atlanta enjoys.

-

About the Architecture +

Built of brick and marble, The Georgian Terrace was designed in the Beaux-Arts style as a means of replicating a grand Parisian hotel. Grand entries are located on both the Peachtree and Ponce de Leon facades, while an outdoor café terrace resides at the street level. The hotel's exterior facing Peachtree Street also features several two-story-high, round-arched openings set under a wide cornice, which is supported by narrow pilasters. The center of the Peachtree facade is set back, although the cornice is not, creating a shallow entrance portico. A change in elevation takes place on the Ponce de Leon side of the building with the ground falling away to the east. The center of the Ponce de Leon facade also has a recessed element that emphasizes the Ladies Carriage entrance -- a projecting portico supported by four columns set on a rusticated arcaded base. This entrance provided access to both the main floor and the lower level of the hotel located underneath the cafe terrace. Above the cornice of the base, both facades remain relatively simple. The operable sash windows have plain limestone sills and transoms. The primary decorative elements are balconettes and detailed spandrels. While the balconettes appear at various levels throughout the building, the spandrels only exist on the first and final stories. The transition between the two facades is achieved by a cylindrical tower device, which is also set back into the building and gives the cornice a rounded-off effect.

The Georgian Terrace itself displays a wonderful blend of Beaux-Arts style architecture, which became widely popular around the dawn of the 20th century. This beautiful architectural form originally began at an art school in Paris known as the École des Beaux-Arts during the 1830s. There was much resistance to the Neoclassism of the day among French artists, who yearned for the intellectual freedom to pursue less rigid design aesthetics. Four instructors in particular were responsible for establishing the movement: Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste, and Léon Vaudoyer. The training that these instructors created involved fusing architectural elements from several earlier styles, including Imperial Roman, Italian Renaissance, ad Baroque. As such, a typical building created with Beaux-Arts-inspired designs would feature a rusticated first story, followed by several more simplistic ones. A flat roof would then top the structure. Symmetry became the defining character, with every building’s layout featuring such elements like balustrades, pilasters, and cartouches. Sculptures and other carvings were commonplace throughout the design, too. Beaux-Arts only found a receptive audience in France and the United States though, as most other Western architects at the time gravitated toward British design principles.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Charles Lindbergh, historic aviator and military officer.

Enrico Caruso, renowned Italian operatic tenor.

Elvis Presley, legendary rock star remembered to history as the “King of Rock and Roll.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, author remember today for writing The Great Gatsby.

Helen Keller, first deaf-blind person in American history to successfully earn a college degree.

Tallulah Bankhead, actress best remembered for her role in Alfred Hitchcock’s film Lifeboat.

Walt Disney, legendary cartoonist and founder of the Walt Disney Company.

Warren G. Harding, 29th President of the United States (1921 – 1923)

Calvin Coolidge, 30th President of the United States (1923 – 1929)

Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States (1977 – 1981)

-

Women in History +

Helen Keller: Helen Keller was among the many guests to visit The Georgian Terrace over the years. Keller herself was the first deaf-blind person in American history to successfully earn a college degree. According to her biographers, Keller had become afflicted with an unknown illness as a toddler, which greatly impacted her sight and hearing. Her family stopped at nothing to get her the best help available, traveling all the way from their native Alabama to meet with eye, ear, and nose physicians in Baltimore. They, in turn, directed the Kellers to inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who had been working with deaf and blind children at the time. Bell informed the Kellers of a school called the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston that would provide the best education for Helen during her youth. Helen Keller was then paired with an alumnus of the academy named Anne Sullivan, who would guide the young girl through her lessons. It was the start of a historic relationship that would be immortalized in a series of films known as The Miracle Worker. Sullivan managed to aid Keller in learning how to communicate through sign language, with her first word being “water.” Keller quickly became proficient at reading sign language with her hands, as well as braille. As she got older, Keller enrolled in The Cambridge School for Young Ladies, and then Harvard University’s Radcliffe College. Keller graduated with top honors from Harvard, leaving the school as a member of Phi Beta Kappa. She then went on to establish a career as an author and motivation speaker that was hailed throughout the world. Keller also had an active political career, becoming a champion for such causes as global pacifism and women’s suffrage. She even helped found the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920. Yet, the cause that Keller is best remembered is her tireless campaigning for the rights of Americans who experienced some form of physical disability. Keller has since received numerous accolades for her work toward the end of her life, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and a place in the National Women’s Hall of Fame.