Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the Atheneum Suite Hotel, which was once a part of a prominent warehouse operated by the descendants of the current Ferry-Morse Seed Company.

Atheneum Suite Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels Worldwide since 2023, dates back to 1879.

VIEW TIMELINEIn 1856, an entrepreneurial businessperson named Dexter Mason Ferry established a seed-growing company in Detroit. Originally hailing from New York, Ferry had relocated to the city in order to participate in its burgeoning industrial economy. He specifically formed the “M.T. Gardner & Company” alongside two partners, Milo T. Gardner and Eber F. Church. Although a rather unassuming enterprise, the company nonetheless prospered considerably. In fact, M.T. Gardner & Company managed to make $6,000 in profit during its first year alone—nearly a quarter of a million dollars in today’s money! Ferry’s success stemmed from his many ingenious business decisions, including the insistence that only fresh seeds were ever packaged for distribution. Indeed, M.T. Gardner & Company continued to expand well into the Gilded Age, with Ferry buying out both of his colleagues. The company’s constant growth even enabled Ferry to construct a massive warehouse complex at the corners of Monroe Street and Beaubien Boulevard during the early 1880s. But tragedy struck when a structural incident forced Ferry to completely rebuild the warehouse in 1886. Undeterred, Ferry seemingly vowed to reconstruct the building to be even grander than its predecessor. To turn his dream into a reality, Ferry had chosen the architectural talents of Gordon S. Lloyd. Lloyd then proceeded to design a gorgeous, sprawling facility that replicated the Romanesque-inspired appearance of fellow architect H.H. Richardson’s Marshall Field Warehouse in Chicago.

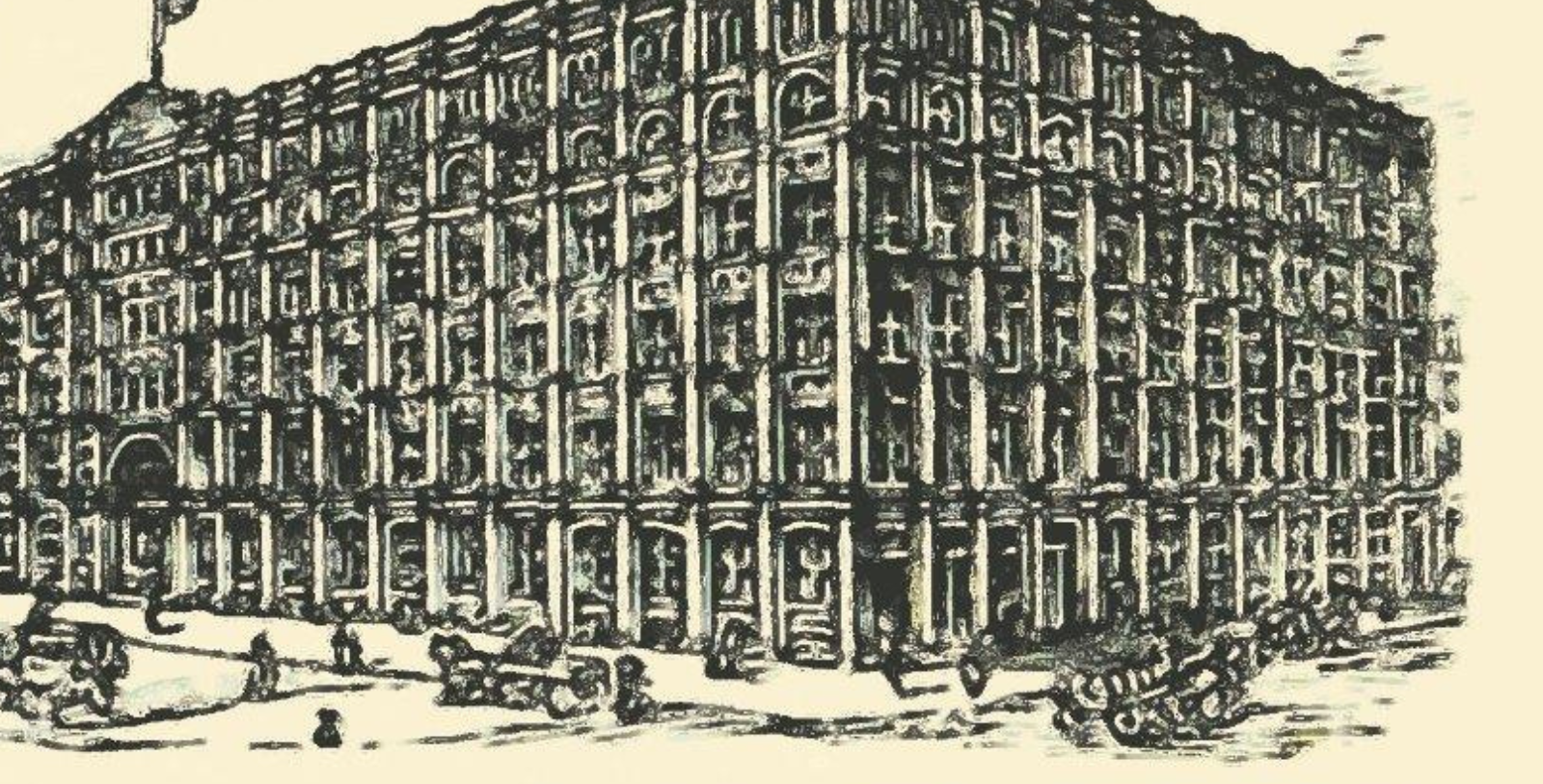

After months of hard work, the new warehouse finally opened a year later. What Lloyd managed to construct was nothing short of an engineering marvel. Debuting as the largest industrial structure in Detroit at the time, the building stood eight stories in height and featured a marvelous façade of brick and limestone trim. The revitalized warehouse also displayed an array of intricately placed fenestrations, anchored by projecting strips of beautiful plaster. Inside, reinforced concrete columns supported the building’s weight, as did mighty steel bars, heavy timber beams, and wrought cast iron. Nevertheless, the ornate warehouse soon began acting as the headquarters of Ferry’s lucrative seed company, which he had renamed as the “D.M. Ferry Co.” The company itself only continued to experience monumental success over the next several decades, ultimately making over $2 million annually at the beginning of the 20th century. The D.M. Ferry Co. saw its various operations expand significantly as such, resulting in its transformation into a major corporation known as the “Ferry-Morse Company” during the 1930s. This prosperity affected the company’s main warehouse in Detroit, too, leading to its expansion three separate times in 1891, 1910, and 1927, respectively. Even though different architects oversaw each renovation, the construction diligently copied the original designs that Llyod had crafted years earlier.

As the Ferry-Morse Company started to extend its market presence throughout the world, it also decided to diversify the location of its business activities. The company thus opted to move out of Detroit throughout the 1950s, leading to the closure of its historic warehouse compound. The facility then sat dormant for many years thereafter, with city officials eventually commissioning its demolition in 1974. However, some portions of the warehouse survived, including the annex developed right before the onset of the Great Depression. Those remaining structures subsequently emerged as prominent landmarks, especially once the U.S. Department of the Interior listed them in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. The site received a renewed lease on life when Jim Papas bought the Depression-era annex during the late 20th century. A Greek immigrant with deep connections to the neighborhood, Papas saw a terrific opportunity to use the structure as the foundation to create Detroit’s first upscale hotel in years. But he also recognized the building’s rich heritage and hoped that the renovations would do much toward preserving its architectural integrity. investing heavily throughout the 1980s, Jim Papas and his team masterfully reforged the historic complex into a breathtaking multi-use urban mall known as Trappers Alley, with the southernmost annex called the “Atheneum Suite Hotel.” Since its debut in 1992, the Atheneum Suite Hotel has since become one of the best places to visit in Detroit, thanks to the dedicated efforts of the Papas family. Jim Papas’ daughter, Athina Papas, is now responsible for guiding it further into the future.

-

About the Location +

Listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Greektown is one of the most historic locations in all Detroit. Still home to a vibrant Greek American community today, this fantastic neighborhood has a rich cultural identity that has managed to endure well into the present. Despite its famous contemporary affiliation to Detroit’s historic Greek demographic, French and German settlers once occupied the district centuries prior. The site of modern-day Greektown was originally part of a sprawling estate known as “Beaubien Farm,” which French fur trader Jean Baptiste Beaubien founded in 1758. The area had functioned as part of the colony of New France at the time and attracted many adventurous French expatriates, including Beaubien. Beaubien and his fellow French colonists proceeded to establish massive farms that extended toward the Detroit River, then the most effective source of transportation and communication in the region. Their estates were designed innovatively, extending along a vertical axis as a way to better share access to the river. Grand farmhouses faced the waterfront, with the agricultural work done in the fields further back inland. Corn emerged as the main good produced among the French inhabitants, although livestock and other crops circulated throughout the nascent settlement. The French presence remained dominant for many years, too, even after the region was integrated within the fledgling United States during the late 18th century.

Beaubien died shortly thereafter though, passing away in 1793. His descendants then lived upon the land for the next several decades until the beginning of the 1830s. The entire site had been absorbed into the borders of Detroit, which had begun growing at a rapid pace. Industry started to appear as such, and with it, mounting numbers of immigrants from across the world. The site of the erstwhile Beaubien farm gradually turned into an urban neighborhood dominated by newly arrived Germans. Initially craftsmen and other kinds of laborers, the German settlers formed the backbone to much of Detroit’s factory workforce. Germans who had more professionalized experience then moved to the area afterward and established a wealth of small businesses. (Perhaps the most prominent type of enterprise that the newer Germans opened were prosperous dry-goods stores.) In time, the entire location had become synonymous with Detroit’s expanding German population, assuming informal names like “Dutchtown” or the “German Quarter.” By the height of the Gilded Age, the district had even come to host more than 17,000 Germans and German Americans! But at the start of the 20th century, the neighborhood underwent a couple significant changes that transformed its character permanently. For instance, some entrepreneurs had decided to construct their own manufacturing plants in the area, giving rise to an industrial character that would persist for generations.

The intrusion of heavy industry into the district subsequently inspired numerous German families to move to different places elsewhere in Detroit. In their wake arrived Greek immigrants, who quickly settled within the remaining residential streets. Mainly hailing from Crete and the Peloponnesus Peninsula, the Greek immigrants eagerly transformed the neighborhood to reflect their own architectural tastes throughout the 1910s. In fact, they created a unique communal environment that soon became known as “Greektown” among fellow Detroiters. Not only did the Greeks thoroughly renovate the existing houses, but they also developed their own quaint homes in the neighborhood. Furthermore, the Greek immigrants also opened a variety of distinctive businesses, such as amazing bakeries and restaurants. While other ethnic groups eventually relocated to Greektown, the area nonetheless remained a steadfast bastion of Greek culture. When commercial development threatened the neighborhood yet again decades later, the Greek and Greek American residents began fighting to preserve its heritage. Indeed, the district emerged as a popular destination for exciting Greek-inspired festivals, and it soon offered impressive institutions that showcased the best of Greek hospitality. Thanks to their concerted efforts, Greektown has since retained its special history and character. Cultural heritage travelers in particular are certain to enjoy the district’s thrilling ambiance and wonderfully preserved historic structures.

-

About the Architecture +

The earlier versions of the hotel showcased a brilliant array of Romanesque-style design principles. This wonderful architectural style first appeared in North America in the middle of the 19th century, as design principles from both Rome and medieval Europe found a popular audience. Architects interested in specializing in Romanesque Revival-themed architecture specifically studied the works of Norman and Lombard engineers who were active in the 11th and 12th centuries. Structures created with the aesthetic are commonly defined by their pronounced round arches and round towers. Yet, those grand archways and towers were far less ostentatious than their historic counterparts located on the other side of the Atlantic. Romanesque Revival-style architecture also implemented squat columns, decorative wall carvings, and the extensive use of masonry. But architects would sometimes favor wood over bricks or stones due to financial concerns. The first wave of Romanesque Revival-style architecture impacted North America in the 1840s and 1850s. But the general public in both the United States and Canada did not fully embrace the aesthetic, preferring the tastes of Italianate and Gothic Revival architecture at the time. It was not until an American architect named Henry Hobson Richardson started using the form in the late 1800s that Romanesque Revival style finally became popular. A graduate from the renowned École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Richardson developed numerous designs in places like New York City, Boston, and Detroit. His approach to Romanesque Revival style was somewhat different, as it also incorporated elements of medieval Mediterranean design principles. His vision of Romanesque Revival-style architecture was soon embraced by other architects, including those in neighboring Canada. Historians today largely refer to Richardson’s design philosophy as “Richardson Romanesque” architecture.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

James Blanchard, 45th Governor of Michigan (1993 – 1996)

Jennifer Granholm, 47th Governor of Michigan (2003 – 2011); 16th U.S. Secretary of Energy (2021 – present)

Gretchen Whitmer, 49th Governor of Michigan (2019 – present)

Michael Dukakis, 65th and 67th Governor of Massachusetts (1975 – 1979; 1983 – 1991)

Debbie Stabenow, U.S. Senator from Michigan (2001 – present)

President Bill Clinton, 42nd President of the United States (1993 – 2001)