Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover The Statler Dallas, Curio Collection by Hilton, which is heraled as America's first modern hotel and is located in the heart of Dallas.

The Statler Dallas, Curio Collection by Hilton was constructed in the years following World War II, in which the United States was defined by the Civil Rights Movement and the Cold War.

Opened in 1956 and built for $16 million dollars, The Statler Hilton Dallas (its original name) was the first major hotel built in Dallas for 30 years. The hotel’s opening inspired celebrities and locals to gather together for a four day celebration. As the last hotel built by the famous Statler chain, it was completed immediately following the acquisition of the Statler Hotels Company by Hilton Hotels Corporation. It was the largest hotel in the Southwest when it opened and featured the largest convention space in the South at that time; its most spacious ballroom could accommodate 2,200 people.

The hotel was outfitted with the latest in architectural and electronic innovations, from usage of a cantilevered reinforced slab system that lent to its impressive height, to its decorative glass and porcelain exterior curtain wall in classic midcentury modern teals, to the vast open interior spaces. It was the first building to ever feature elevator music and the first hotel to install new and custom 21” Westinghouse televisions in each guestroom and suite. The hotel uniquely featured a heliport on its roof, to which guests were airlifted from Dallas’ local and surrounding airports. The Statler Dallas, Curio Collection by Hilton iconic stature was solidified when the American Institute of Architecture’s Dallas Guide called the hotel and the library located next door, designed by George Dahl in 1953, “the best block of 1950s architecture in the city.”

Unfortunately, time and neglect took its toll on The Statler Dallas, Curio Collection by Hilton. In 2001, the hotel closed. It was nearly demolished in 2003. Preservation Dallas added the building to its list of Most Endangered structures in both 2007 and 2008; the National Trust for Historic Preservation chose The Statler to be one of “America’s Most Endangered Places” due to its representation of American midcentury design. There were several attempts at redeveloping the hotel. In 2012, developer Leobardo Trevino’s crew uncovered an original 40-foot long mural by artist Jack Lubin from 1956, located in what was once the Empire Room supper club. The hotel was ultimately purchased by Centurion American Development Group in September 2013.

Through preservation efforts and the help of state and federal tax credits, The Statler Dallas, Curio Collection by Hilton has been restored to its former glory. With a $175 million renovation of the hotel, it was the largest tax credit project in Texas and has now been listed as one of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places success stories. The Statler Dallas, Curio Collection by Hilton now includes the hotel with 159 guestrooms, 219 private apartment residences on the upper 11 floors, a state-of-the-art concert venue, meeting facilities including a 14,500 square foot ballroom, four dining outlets, and retail and office space.

-

About the Architecture +

When it was built, The Statler Dallas, Curio Collection by Hilton was outfitted with the latest in architectural and electronic innovations, from usage of a cantilevered reinforced slab system that lent to its impressive height, to its decorative glass and porcelain exterior curtain wall in classic midcentury modern teals, to the vast open interior spaces.

Guest Historian Series

Read Guest Historian SeriesNobody Asked Me, But… No. 216;

Hotel History: Ellsworth M. Statler

By Stanley Turkel, CMHS

In 1950, the hotel industry named Ellsworth Milton Statler “Hotel Man of the Half Century”, even though he had been dead for 22 years. Statler’s impact on inn-keeping was so great, no one else even came close.

While many considered Statler the premier hotel figure, he was not a typical executive. A plain, rugged man who started to work at the age of nine, he continued to wear twenty dollar suits and four dollar shoes even after he became successful, and resembled Will Rogers more than Rudolph Valentino.

When The Statler Dallas, Curio Collection by Hilton began in the hotel business, the following practices were commonplace:

- Some hotels embarrassed non-paying male guests by cutting off their trousers at the knees and making them parade in the lobby with sandwich signs that proclaimed them as “deadbeats.”

- One hotel forbade guests from spitting on the carpets, lying in bed with their boots on, or driving nails into the furniture.

- Even the better hotels had shared bathroom facilities. Bathtubs were usually built on a platform, and hot water cost 25 cents extra.

- About 90 percent of hotels were American plan, with cheap, unlimited food included in the room rate.

- Smoking was usually not permitted in dining rooms, bars barred women, and wine and beer sold better than liquor.

- Rooms were heated with stoves or open fireplaces. Signs reminded guests not to blow out the gas jets.

- No hotel owner called his house full until all double beds were fully occupied, often by complete strangers. Talk about yield management.

Statler was more interested in comfort in his hotels than fancy trimmings. “A shoe salesman and a traveling prince want essentially the same thing when they are on the road – good food and a comfortable bed – and that is what I propose to give them,” he said. To counter criticism that his hotels were not luxurious enough, Statler said, “I could run a so-called luxury hotel or a resort hotel that would beat any damn thing those frizzly-headed foreigners are doing, but I just don’t operate in that field. All I want to do is to have more comforts and conveniences and serve better food than any of them have or do, and mine will be at a price ordinary people can afford.”

Statler was born on a farm near Gettysburg, PA on October 26, 1863, the son of William Jackson Statler and Mary Ann McKinney. When he was young, the family moved to Bridgeport, Ohio across the Ohio River from Wheeling, West Virginia. Statler and his brothers worked hard and hot at the La Belle Glass Factory in Kirkwood, OH, tending glory holes, small furnaces used to heat and soften glass so it could be formed into bottles or other products. Statler landed in the hotel field as a nighttime bell-boy at the McLure House Hotel in Wheeling.

At 15, Statler who had begun work at $6 a month, board and tips, was promoted to head bellman. By the following year, Statler had learned how to keep accounting records, and at 19, he became hotel manager.

In 1878, the McLure House had an elevator, but it was reserved for guests and the manager. Bellboys had to use the stairs to carry luggage and guest necessities like hot water and kindling. Guestrooms were barely adequate, furnished only with a bed, a chair, and a large clothing hook on the door. Apparently, the McLure’s saloon was more in tune with guest needs, offering a free lunch buffet consisting of cold meats, hard-boiled eggs and rye bread. A large painting of a nude female hung over the bar.

Enterprising and innovative, Statler leased the hotel’s billiard room and railroad ticket concession and made them profitable. He got help from an unexpected source: younger brother Osceola had developed an amazing talent for billiards. Osceola’s fame brought people to the hotel to watch the local champion defeat players from out-of-town. Statler bought out the company that ran the nearby, four-lane Musee Bowling Lanes, added four additional lanes and installed eight pool and billiard tables. He then organized a city-wide bowling tournament with a grand prize of $300 for the winning team.

“The Pie House” in the Musee building, served his mother’s pies, minced chicken and minced ham sandwiches on egg-shell china with quadruple-plated table silver. The place was so busy, that the pin boys in the bowling alleys had to spend their spare time cranking the ice-cream freezers.

The family business thrived with Osceola as manager of the billiard room; brother Bill had charge of the bowling lanes; mother Mary and sister Alabama turned out sandwiches and pies. As for Ellsworth, a $10,000 annual income allowed him to pursue his dream: to own and operate a 1,000-room hotel in New York City. Ultimately, he fulfilled it, following the old vaudeville line that to get to New York City, you had to go by way of Buffalo.

Statler used to go fishing with friends in the St. Clair River at Star Island in Canada. In 1894, on his way home, he stopped in Buffalo where he observed the Ellicott Square building under construction, billed as “the largest office building in the world”. He learned that management was looking for an operation for a large restaurant for $8,500 per year rental. Statler struck a deal to lease the space provided he could raise enough money to furnish a large restaurant. That summer, Statler also married Mary Manderbach, whom he had met in Akron eight years earlier. They moved to Buffalo, opening Statler’s Restaurant July 4, 1895 with fireworks and patriotic oratory.

Statler staked all on a convention of the Grand Army of the Republic that would bring thousands of Union Army veterans and their families to Buffalo. He widely advertised a menu offering “all you can eat for 25¢.” The quarter bought bisque of oysters, olives, radishes, fried smelts with tartar sauce and potatoes Windsor, lamb sauté Bordelaise with green peas, roast young duck with applesauce and mashed potatoes, Roman punch, fruit or vegetable salad with Russian dressing, cream layer cake, Metropolitan ice cream, coffee, tea or milk. What’s more, you could eat as much as you liked.

In 1907, Statler built and opened the 300-room Buffalo Statler, launching a chain of middle-class hotels that standardized comfort and cleanliness. Seeking a competitive edge, he designed the “Statler plumbing shaft.” This enabled bathrooms to be built back to back, providing two baths for little more than the price of one and allowing him to offer many private rooms with adjoining baths. Statler’s preoccupation with comfort and efficiency brought about the following innovations: ice water circulating to every bathroom, a telephone in every room, a full-sized closet with a light, a towel hook beside every bathroom mirror, a free morning newspaper, and a pin cushion with needle and thread. In 1922, at the Pennsylvania Statler in New York City, Statler introduced the Servidor, a bulging panel in the guestroom door where the guest hung clothes for cleaning or pressing. The valet could pick up and return them without entering the room. The Pennsylvania Statler also was the first hotel to offer complete medical services including an X-ray and surgical room, a night physician and a dentist.

Statler was also concerned about making certain staff focused on guest satisfaction. When he established his first hotel, he said “a hotel has just one thing to sell. That one thing is service. The hotel that sells poor service is a poor hotel. It is the object of the Hotel Statler to sell its guests the very best service in the world.”

Statler’s precepts eventually became the “Statler Service Code,” a formulation for employees the founder’s ideals. The code aroused so much interest that it was made available to guests and became a Statler tradition. Long before “empowerment” became a cliché, every Statler employee signed off on a pledge including these:

- To treat our patrons and fellow employees in an interested, helpful, and gracious manner, as we would want to be treated if positions were reversed;

- To judge fairly – to know both sides before taking action;

- To learn and practice self-control;

- To keep our properties- buildings and equipment- in excellent condition at all times;

- To know our job and to become skillful in its performance;

- To acquire the habit of advance planning;

- To do our duties promptly; and

- To satisfy all patrons or to take them to our superior.

Statler’s widow, Alice managed to keep the company solvent during the Depression. She ran Statler Hotel Co. until 1954, when she sold it to Hilton Hotels for $111 million, merging Statler’s 10,400 rooms with Hilton’s 16,200. That was the greatest hotel merger and largest private real estate deal in history up until that time.

*****

About Stanley Turkel, CMHS

Stanley Turkel is a recognized consultant in the hotel industry. He operates his hotel consulting practice serving as an expert witness in hotel-related cases and providing asset management an and hotel franchising consultation. Prior to forming his hotel consulting firm, Turkel was the Product Line Manager for worldwide Hotel/Motel Operations at the International Telephone & Telegraph Co. overseeing the Sheraton Corporation of America. Before joining IT&T, he was the Resident Manager of the Americana Hotel (1842 Rooms), General Manager of the Drake Hotel (680 Rooms) and General Manager of the Summit Hotel (762 Rooms), all in New York City. He serves as a Friend of the Tisch Center and lectures at the NYU Tisch Center for Hospitality and Tourism. He is certified as a Master Hotel Supplier Emeritus by the Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Lodging Association. He served for eleven years as Chairman of the Board of the Trustees of the City Club of New York and is now the Honorary Chairman.

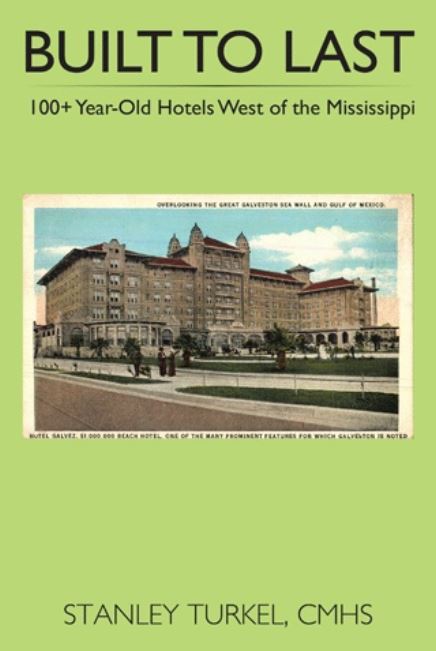

Stanley Turkel is one of the most widely-published authors in the hospitality field. More than 275 articles on various hotel subjects have been posted in hotel magazines and on the Hotel-Online, Blue MauMau, Hotel News Resource and eTurboNews websites. Two of his hotel books have been promoted, distributed and sold by the American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute (Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry and Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi). A third hotel book (Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York) was called "passionate and informative" by the New York Times. Executive Vice President of Historic Hotels of America, Lawrence Horwitz, has even praised one book, Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry:

- “If you have ever been in a hotel, as a guest, attended a conference, enjoyed a romantic dinner, celebrated a special occasion, or worked as a hotelier in the front or back of the house, Great American Hoteliers, Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry is a must read book. This book is recommended for any business person, entrepreneur, student, or aspiring hotelier. This book is an excellent history book with insights into seventeen of the great innovators and visionaries of the hotel industry and their inspirational stories.”

Turkel was designated as the “2014 Historian of the Year by Historic Hotels of America,” the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. This award is presented to an individual for making a unique contribution in the research and presentation of history and whose work has encouraged a wide discussion, greater understanding and enthusiasm for American History.

Works published by Stanley Turkel include:

- Heroes of the American Reconstruction (2005)

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 1 (2019)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

Most of these books can be ordered from AuthorHouse—(except Heroes of the American Reconstruction, which can be ordered from McFarland)—by visiting www.stanleyturkel.com, or by clicking on the book’s title.