Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

henley park hotel history

Discover The Henley Park Hotel, which has been home to Washington, D.C.'s political and social elite since opening in 1918.

The Henley Park Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 1994, dates back to 1918.

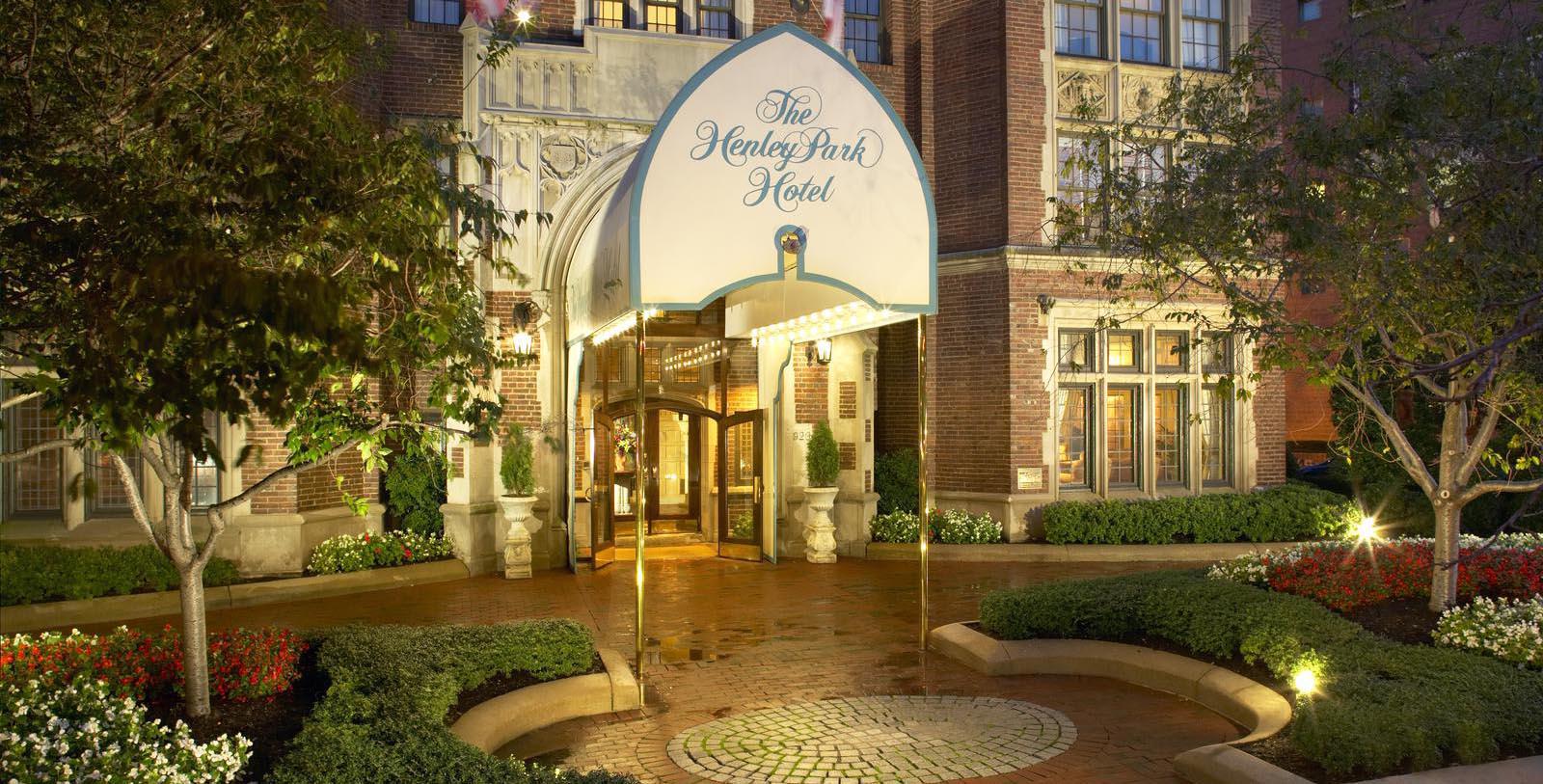

VIEW TIMELINEThe Henley Park Hotel stands today as one of the most upscale holiday destinations in downtown Washington, D.C. But this gorgeous building has not always been a historic hotel. On the contrary, the history of The Henley Park Hotel began over a century ago when it was founded as an incredibly luxurious apartment complex called the “Tudor Hall Apartments.” Constructed toward the end of World War I, the name “Tudor Hall” was inspired by its unique architectural motifs. Indeed, the architects who created the structure relied heavily on aspects of Tudor Revivalism to craft its magnificent façade. Distinctive architectural details were included in the design, including traditional archways and leaded glass moldings. The exterior walls even displayed 119 gargoyles—two of which depict the lead architect and his wife. Inside, the architects made every single living unit resemble the rustic ambiance of a historic English country manor. Among the most unique aspects of the interior floorplan were its resplendent Mercer tiling. Upon its debut in 1918, the new Tudor Hall Apartments swiftly established a reputation for its high-end residential accommodations and attentive staff. Word of its grand appeal soon spread across Washington, which inspired numerous people to attempt to sign a lease. In fact, the structure’s most common occupants were dozens of U.S. congressmen, who enjoyed the building’s unrivaled elegance and its central location. The Tudor Hall Apartments remained incredibly renowned for decades thereafter, although its luster eventually began to decay by the end of the century. Fortunately, the historic structure was saved when RB Properties acquired the site in 1982. It subsequently invested heavily into its renovation and turned it into “The Henley Park Hotel.” Great care was taken to preserve its architectural integrity, as most of the original features remain intact today. Perhaps the most endearing quality that exists are the stained-glass initials "T.H." for "Tudor Hall," which is still visible above the side door of what is now the Wilkes Room. A proud member of Historic Hotels of America since 1994, The Henley Park Hotel continues to celebrate its rich heritage and fantastic style.

-

About the Location +

Washington is among the nation’s most historic cities, having been founded more than two centuries ago by the Founding Fathers. In 1790, Congress specifically passed the “Resident Act” after James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton agreed to create a permanent national capital in the southern United States. Known as the “Compromise of 1790,” the men decided to place the future settlement somewhere in the South in exchange for the federal government paying off each state’s debt accrued via the American Revolutionary War. George Washington—who was serving his first term as President—then carefully looked for the site of the new city in his role as the country’s chief executive. He spent weeks searching for the perfect spot before finally settling upon a plot of land near the mouth of the Potomac River. Washington had felt that the location was in a terrific spot, for it was still roughly in the middle of the nation. Furthermore, he hoped its proximity near major seaports would further bind the emerging western states with the more established Atlantic coastline. Maryland and Virginia subsequently donated around 100 acres at Washington’s site, although Virginia would later rescind its donation in 1847.

Nevertheless, work on the capital began a year later and lasted for the duration of the decade. At the start of the project, the three federal commissioners in charge of supervising its progress decided to name the nascent settlement after the President himself. (They also named the federal district surrounding the city as “Columbia,” a feminine adaptation of Christopher Columbus’ name.) Noted French architect Charles L’Enfant spearheaded the city’s new design, who presented a bold vision that featured wide boulevards and ceremonial spaces reminiscent of his native Paris. But despite L’Enfant’s grand plans for Washington, only the first iterations of the United States Capitol, the White House, and a couple other prominent governmental structures appeared at the time. Barely any other buildings stood in the city when the entire federal apparatus relocated from Philadelphia to Washington in 1800. Life in early Washington was hard, too, for its residents were constantly beset by disease, poor infrastructure, and local economic depressions. What few residents remained in the city year-round endured the worse hardships during the War of 1812, when the British notoriously ransacked the community. In fact, the British had even torched the Capitol, the Treasury, and the White House.

Washington did not finally start to develop into an actual city until the middle of the 19th century, after investment in its upkeep increased dramatically. While additional federal buildings—including the General Post Office and the Patent Office—first appeared in the 1830s, a wave of municipal and residential construction flourished in the wake of the American Civil War. But much of the construction was conducted under the auspices of a territorial government that initiated dozens of new buildings projects, including the development of schools, markets, and townhouses. Streets were also paved for the first time, while modern sanitation systems were created for the many new neighborhoods debuting throughout the city. Congress even contributed to the local construction, especially after the territorial government bankrupted itself shortly after its founding. But the federal government had also created some of the city’s most iconic structures on its own at the same time, such as the Washington Monument, the National Mall, the Library of Congress complex, and a new United States Capitol. The climax of all this construction work materialized with the Senate Park Commission—remembered more commonly as the “McMillan Commission”—which offered a comprehensive series of plans to beautify the entire city.

It would take years to complete the recommendations of the McMillan Commission’s, though. Buildings and landscape designs that reflected the commission’s research appeared throughout the first half of the 20th century, especially once the federal government became more involved in international affairs after World War I. Dozens of art galleries, storefronts, and restaurants proliferated, transforming Washington into one of the nation’s most esteemed cultural capitals. Many new embassies also debuted within the city along Massachusetts Avenue, giving rise to its iconic area of Embassy Row. Dozens of new monuments appeared throughout Washington, too, such as the iconic Lincoln Memorial. Some of the most significant construction transpired during the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, which helped spur the creation of an official U.S. Supreme Court building, The Pentagon, and the famous Federal Triangle. Washington nonetheless fell into a brief period of decline around the start of the Cold War that was only reversed with the committed efforts by Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson to invest heavily into its upkeep. Today, Washington is now among the most powerful cities in the whole world, as well as one of its most gorgeous. Thousands of people from all over flock to the city each year to take in its prestigious culture and heritage.

-

About the Architecture +

Constructed in 1918, The Henley Park Hotel displays elements of Tudor Revivalism. Tudor Revival architecture is normally best defined as an eclectic mixture of late medieval building traditions that influenced the appearance of English villages during the Middle Ages. The form specifically attempted to emulate the historical character of the feudal cottage that once dominated England’s landscape. The name “Tudor” is somewhat of a misnomer, though, for the design aesthetic does not borrow any of its principles from buildings constructed during the reign of the 16th century Tudor monarchs. Tudor Revival style first became prevalent in the United Kingdom at the beginning of the 20th century, when architects were exploring alternative ways to connect better with the past. Tudor Revival was specifically applied to residential homes, although some commercial structures—like hotels—also bore the unique appearance. It then jumped across the Atlantic to the United States, where it was second only in popularity to Colonial Revival architecture. Architects at the time had been motivated by the various revivalist movements spawned from the World’s Fair of 1893—known as the “Columbian Exposition”—which encouraged artists and intellectuals to embrace romanticized versions of history.

Buildings constructed with Tudor Revival-style architecture were typically identified by their half-timbering. In essence, “half-timbering” is the practice of constructing a series of interlocking load-bearing timber frames that were then filled with some kind of plaster mold. As such, the architects left the frame exposed, creating a visibly distinctive appearance. Another common characteristic of Tudor Revival-themed buildings was the presence of a steeply pitched roof that usually featured heavy shingles. This area of the structure was often lined with overhanging gables, as well as eaves and diamond-shaped casement windows. In many cases, the architects endeavored to make the roof appear as if it had been thatched. Stone chimneys also protruded from the roof, conveying rich details. A wonderful, round arched doorway guided guests into the interior, too, which featured an irregular floor plan. The use of such a layout was normal inside late medieval English homes, as it usually took several generations to build. Modern architects hence attempted to capture that ambiance whenever they set about creating the blueprints for Tudor Revival-style buildings. Today, Tudor Revival-style architecture is cherished for its ability to ensconce its tenants with a charmingly tranquil atmosphere.