Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover The Bolling Wilson Hotel, a wonderful classically inspired destination that serves as a time capsule for Wytheville and Southwestern Virginia.

The Bolling Wilson Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2025, dates to 1927.

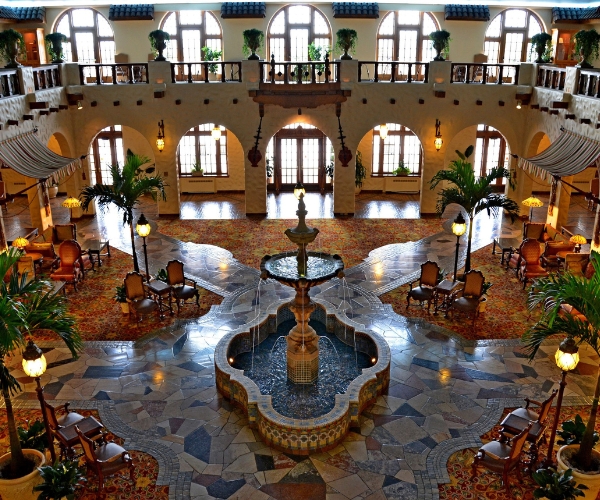

VIEW TIMELINEDuring the early 20th century, the community of Wytheville, Virginia, was rapidly experiencing significant cultural transformations. Ongoing efforts to improve the local infrastructure had turned the village into a bustling regional transportation center, leading to all kinds of goods and people passing through regularly. Perhaps the most notable development had been the Norfolk and Western Railway, which connected Wytheville to much larger cities across Appalachia. With the increase in travel, members of the Wytheville Rotary Club created a gorgeous hotel in the heart of town. To that end, the organization hired the accomplished Virginia-based firm Frye and Stone to craft its appearance, which went to work raising the building in the mid-1920s. The company's design was masterful, calling for the use of an eclectic combination of distinctive architectural styles that blended incredibly well together. Symmetrically placed square-headed windows proliferated all over the facade, while the top story displayed ornamental features, such as bonded brick panels, free-standing urns, and beautiful paterae. Neoclassical features dominated the exterior, including a stunning one-story portico with a series of striking Corinthian columns. This rich detailing continued inside, too, as the architects had outfitted the public venues with more classically inspired elements like capitals, archways, and crown molding.

Named the "George Wythe Hotel" upon its debut in 1927, the business quickly became the epicenter for all social gatherings in Wytheville, whether they involved weddings, reunions, or corporate meetings. (The name was a homage to George Wythe, one of Virginia's signers of the Declaration of Independence and namesake of Wytheville.) Much of the hotel's initial success came from its proximity to several major thoroughfares that cut through the town. The rates offered were also some of the finest in the whole state, charging a then-competitive $1.50 for a single room and $2.50 for a double room! The hotel's grand appeal endured for years to come, especially once newer roads, including the sprawling Lee Highway, brought unprecedented amounts of automobile traffic to the area. Indeed, the George Wythe Hotel prospered well into the middle of the century, serving as a prominent fixture in Wytheville for generations. By the 1970s though, the building started to face tougher competition from other neighboring hotels in places like Roanoke, making it difficult for the owners to stay open. Unfortunately for Wytheville, attempts to keep the hotel financially afloat eventually failed, resulting in its permanent closure. Although a few entrepreneurial businesspeople tried resurrecting the site periodically over the following years, its fate nonetheless remained uncertain at the beginning of the 21st century.

But the erstwhile George Wythe Hotel survived as an important community landmark in the minds of many throughout Wytheville, stirring locals Bill and Farron Smith to acquire the facility in 2010. Through their company Smith Enterprises, the Smiths enacted an extensive renovation process that spent months diligently reviving the building's architectural integrity. However, the Smiths adopted an interesting approach to the project, instituting an ambiance that paid tribute to another resident of Wytheville—former First Lady Edith Bolling Wilson. In fact, the modern components the Smiths installed incorporated aesthetics that commemorated Edith Bolling Wilson's life and legacy! (Wilson was even a guest back when the building operated as the "George Wythe Hotel," having visited while attending a church dedication happening elsewhere in town. Now known as the "Bolling Wilson Hotel," this fantastic historic site has since resumed its place as one of the best holiday destinations to visit in western Virginia. Furthermore, the hotel's renovation has played a significant role in the ongoing revitalization of Wytheville, encouraging tourists and residents alike to invest their time downtown. From its early days as a bustling hub of commerce and social activity to its rebirth, the hotel has remained a fundamental part of Wytheville's identity. The efforts of Bill and Farron Smith to restore the hotel have not only preserved a piece of the region's history but contributed to its contemporary growth.

-

About the Location +

Named after George Wythe, a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence and mentor to Thomas Jefferson, Wytheville's historic origins trace all the way back to the late 18th century. More specifically, three men--Chris Simmerman, John Davis, and Robert Williams II—had donated a combined 145 acres for the development of a town capable of serving as the administrative seat for the newly minted Wythe County. The group then had the land surveyed several months later, dividing the space into half-acre lots designated for construction. Although the community's subsequent growth was initially slow, it nonetheless managed to expand gradually over the following decades. In fact, Wytheville maintained a population of nearly 500 residents by the middle of the century, making the settlement one of the largest in all of Southwestern Virginia. Spurring this expansion had been the emergence of then-innovative infrastructural projects, including the nearby extension of the prominent Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. The railroad in turn made Wytheville a desirable transportation network for all kinds of goods, especially the iron ore mined from deposits located in the neighboring villages of Austinville and Ivanhoe. This unique economic character gave Wytheville some strategic importance once the American Civil War finally began, with the Confederates relying heavily upon iron shipments sent out of the town.

In consequence, the Union army looked to Wytheville as a target for periodic raids, assigning various cavalry units to strike at its local freight depot. The most significant attack occurred when Union Colonel John Toland led an undersized brigade of horsemen against Wytheville's garrison in 1863. Known as "Toland's Raid," the assault saw the colonel and some 800 troopers approach the town on the evening of July 18, aiming to not only tear up railroad tracks but also destroy whatever supplies were awaiting departure. However, the community had been forewarned of the looming raid and began hastily preparing defenses in the heart of town. While many in Wytheville fled south or hid in their homes, a force of about 120 civilians volunteered to fight the oncoming cavalry. Toland's men entered the community first, charging down the main road haphazardly in parade formation. The decision proved to be a fateful one though, as the makeshift Confederate force managed to spring a successful ambush. Firing muskets from hidden alcoves, the defenders exacted great casualties on the Union forces. Among the dead was Colonel Toland, who was shot at the head of the column. Despite suffering significant losses, the Union brigade was eventually able to secure the town, albeit for merely a single day. But they had failed to inflict any damage to Wytheville's train depot and its accompanying stock of supplies.

Wytheville has since preserved much of its remarkable heritage in the present, featuring several museums and historic sites that guests today can explore. For instance, visitors will notice the unique Civil War Trail signs featured throughout the town, conserving the memory of events like Toland's Raid. The Wytheville Training School Cultural Center—the region's only African American Heritage Museum— highlights the history of Black education in Wythe County. A former school originally constructed in 1882, the facility operated until the mid-20th century and now serves as a testament to the area's greater African American community. The birthplace and childhood home of First Lady Edith Bolling Wilson—the only Appalachian-born First Lady—is another significant site in Wytheville, which is dedicated toward preserving her rich national legacy. Furthermore, visitors can discover the neighboring Shot Tower, an immense edifice built three centuries ago to help manufacture metal goods. Indeed, lead shipped from the nearby Austinville Mines melted and poured through a sieve, falling through the tower into an additional 75-foot shaft that broke the ore down further. Now listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, this fantastic site has since offered any interested visitors a glimpse of Wytheville's industrious past. Today, Wytheville is truly a vibrant community that commemorates its past while looking towards the future. With its majestic mountains, sparkling waters, and rolling hills, Wytheville continues to captivate those who explore its historic streets and landmarks.

-

About the Architecture +

Although the Bolling Wilson Hotel now displays many historic architectural styles, the most noticeable are its Classical Revival-inspired motifs. Also known as "Neoclassical," Classic Revival design aesthetics are among the most common architectural forms seen throughout the United States. This wonderful architectural style first became popularized at the World's Columbian Exposition, which was held in Chicago in 1893. Many of the exhibits displayed architectural motifs from ancient societies like Rome and Greece. As with the equally popular Colonial Revival style of the same period, Classical Revival architects found an audience for their more formal nature. It relied on stylistic design elements that incorporated structural components like the symmetrical placement of doors and windows, and a front porch crowned with a classical pediment. Architects would install a rounded front portico that possessed a balustraded flat roof. Pilasters and other sculptured ornamentations proliferated throughout the façade of the building. The most striking feature of Classical Revival-style architecture was its massive columns that displayed some combination of Corinthian, Doric, or Ionic capitals. With its Greco-Roman temple-like form, Classical Revival-style architecture was considered most appropriate for municipal buildings, including courthouses, libraries, and schools. But the aesthetic found its way into more commercial use over time, such as banks, department stores, and of course, hotels.

In addition, Colonial Revival features are prevalent throughout the building's design. Colonial Revival architecture is the most widely used building form in the entire United States. It reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to the aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America's disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation's history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country's formative years. As such, structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture featured such components as pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined Colonial Revival-style exteriors, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, as well. This building's form remained immensely popular for years until petering out in the late-20th century. Nevertheless, architects today still rely upon Colonial Revival architecture, using the form to construct all kinds of residential buildings and commercial complexes. Many buildings constructed with Colonial Revival-style architecture are even identified as historical landmarks at the state level, and the U.S. Department of the Interior has even listed a few of them in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Edith Bolling Wilson, former First Lady of the United States (1915 – 1921)

-

Women in History +

Edith Bolling Wilson: The most famous guest to ever visit the hotel was the building's current namesake, former First Lady Edith Bolling Wilson. A native of Wytheville, Edith Bolling Wilson was born into the prestigious Bolling family whose origins harkened back to the very founding of Virginia. Despite the grandeur of her lineage, Edith's formal education was nonetheless limited. In fact, she was primarily educated at home by her grandmother, who taught her to read and write. But Edith possessed a sharp mind, a strong will, and a commanding presence—qualities that would later define her character in the national consciousness. Then in 1896, Edith married Norman Galt, a prosperous jeweler based in Washington, D.C. The marriage brought her into the social circles of the capital, where she developed a reputation for her elegance and independence. However, Norman soon passed away, leaving Edith a wealthy widow at just 36. But in 1915, her life took a dramatic turn when a mutual friend introduced her to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. Recently widowed himself, the connection between the president and Edith proved to be truly intense. Within months, Wilson proposed, and—disregarding concerns about the political optics of a quick remarriage—they wed that December.

Now serving as First Lady of the United States, Edith Bolling Wilson approached her newfound responsibilities conventionally at first. But her life—and the course of American history—changed dramatically when President Wilson became incapacitated from a stroke in October 1919. In an era before the 25th Amendment (or any other clear protocols for presidential disability), the nation faced a constitutional crisis. It was then that Edith stepped into an unprecedented role. Shielding the severity of Wilson's condition from the public, the press, and even members of Congress, she assumed what she called a "stewardship" of the presidency. More specifically, she controlled access to the president, reviewed official documents, and decided what matters were important enough to bring to his attention. Cabinet members and senators were often forced to communicate through her in turn, which transformed Edith into something of a gatekeeper for executive power. Critics subsequently accused her of running the government furtively, dubbing her "the Secret President" and "the first woman to run the government." While Edith insisted, she had merely facilitated communication; her influence upon the federal government was undeniable.

Some historians have since argued that her actions were necessary to preserve stability amid a time of national emergency, but others contend that she overstepped constitutional boundaries. Whatever the opinion, Edith's involvement has been one of the most extraordinary moments of the presidency. Nevertheless, the couple retired to a quiet life after President Wilson's second term ended in 1921, with Edith continuing to care for her husband until his death three years later. She then spent the following decades preserving his legacy, overseeing the publication of his papers, and supporting the creation of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation. Edith eventually lived through the early 1960s—dying at the age of 89—and was buried beside her husband at the Washington National Cathedral. Edith Bolling Wilson's life was a remarkable journey from the rural fields of western Virginia to the heart of American power. Her story challenges traditional narratives about the role of First Ladies, raising enduring questions about leadership, transparency, and the limits of authority. Whether seen as a devoted wife or a de facto president, Edith's legacy is one of complexity and intrigue. Indeed, few First Ladies have wielded such influence—or faced such scrutiny. In the end, Edith Bolling Wilson's tenure in the White House redefined the boundaries of the role and left a legacy that continues to inspire debate and fascination.