Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

historic hotel in washington d.c.

Discover the Phoenix Park Hotel with its Irish manor house feel.

Phoenix Park Hotel, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2002, dates back to 1927.

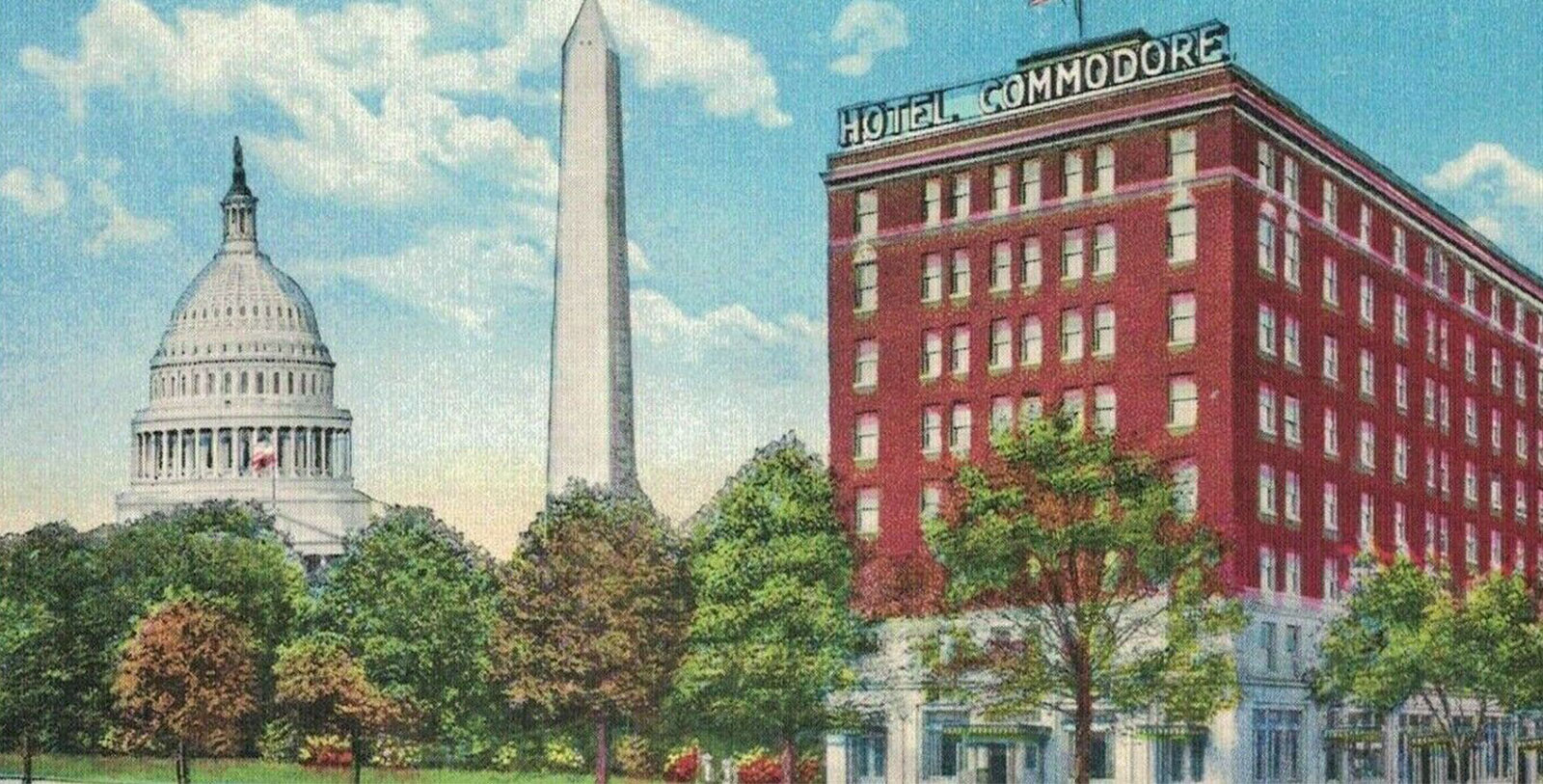

VIEW TIMELINEThe Phoenix Park Hotel—originally the Commodore—is one of the very few hotels around Union Station that survive from the days when almost everyone who visited Washington arrived by train. The magnificent railroad terminal, opened in 1907, once served as the primary transportation gateway to the nation’s capital, welcoming visitors from far and wide. In the decades after it was built, countless thousands of newcomers disembarked from their trains and wandered outside in search of a place to stay. Strategically located a short block away at North Capitol and F Streets NW, the Phoenix Park/Commodore was an easy choice. A group of Washington investors announced plans to build the hotel in May 1926. They originally planned to call it the “Milestone,” projecting that it would contain 140 guestrooms and cost $750,000. The guestrooms were tiny by today’s standards, but each included a private bath—a feature that was becoming standard around this time. It was a full-service hostelry with a comfortable lobby, reading room, stores, and restaurant filling the ground floor. The building’s accomplished architect, Frank G. Pierson, would go on to design the nearby Bellevue and Stratford hotels, as well as the Library of Congress’s Adams Building. For the Commodore, Pierson adopted a Georgian Revival style, accenting the building’s functional brick façade with elegant, classically trimmed limestone cladding. (This cladding appeared on the first two floors, along with large ground-floor display windows.) This historic Washington, D.C. hotel continues to stand as a testament to the city's rich architectural and cultural heritage.

Completed in the spring of 1927, the hotel was christened the “Commodore” (not the Milestone) and was originally managed by the New York-based Intercity Hotels Corporation. In 1932, a room at the Commodore could be had for $2.50 per night. The hotel’s cocktail lounge, the Cork and Bottle, drew local residents, Capitol Hill staff, and out-of-towners alike. In 1937, restaurateur Jack Melrose told the Washington Post that the place was “just crowded to the gills.” Melrose also ran the hotel’s Melrose Restaurant, which offered full dinners for a single dollar in 1944. (A menu from that year even warned customers that the cocktail lounge’s hours would be limited due to scarcity of liquor—one of many shortages that plagued the country in the 1940s.) The years after World War II saw widespread decline in the more historic parts of downtown Washington, including the Union Station area. As travelers increasingly rode airplanes instead of trains, business dwindled. Hotel managers, including the Commodore’s, offered specials to lure guests, such as free rooms for children under 14 accompanied by their parents. For instance, when a couple from Puerto Rico and their eight children showed up to stay at the Commodore in July 1960, manager J.F. McCormick subsequently posed cheerfully in a newspaper photograph with them to celebrate their bargain accommodations.

The hotel’s fortunes began to turn for the better in 1974, when restaurateur Daniel J. “Danny” Coleman opened the Dubliner, an Irish Pub, in the ground floor restaurant space. Coleman had grown up working in his immigrant Irish father’s pub in Syracuse, New York, and he was determined to bring a similarly authentic dining space to D.C. (The new location was historically fitting; this neighborhood, known as “Swampoodle” in the 19th century, had been home to poor Irish immigrants, many of whom worked in the nearby Government Printing Office.) Coleman’s pub was one of the first successful watering holes to draw people back to the neighborhood and help revive its fortunes, but the hotel itself had seen better days. When it became available for purchase in 1980, Coleman seized the opportunity to extend the Irish theme to the entire building. Rechristening it the Phoenix Park, after Dublin’s famed 1,760-acre urban park, Coleman and his partners renovated the hotel, increasing room sizes and adding facilities for meetings and parties. The massive renovation, completed in 1982, resulted in a luxurious, boutique hotel that celebrated the Commodore’s architectural heritage, while adding a new penthouse floor on top of the historic building.

The Phoenix Park became a mecca for politicians and other VIPs seeking luxury accommodations in the relaxed and intimate setting of a boutique hotel close to the U.S. Capitol, Union Station, and U.S. Senate office buildings. In 1995, Coleman and his partners undertook another major renovation of the hotel, this time expanding it significantly by installing a new adjoining tower on the south side of the building, doubling the number of rooms to 149, and adding a new ground-floor ballroom. The expansion came just in time for a major initiative, spearheaded by former Senator George Mitchell, to broker a peace deal in Northern Ireland. Irish politicians coming to the U.S. to negotiate an agreement stayed at the Phoenix Park Hotel, and the Dubliner served as their primary rendezvous while negotiating what would be known as the Good Sunday Agreement. Having found its niche, the Phoenix Park has continued to prosper and attract distinguished guests, including President Bill Clinton, Senator Ted Kennedy, and Speakers of the House Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill and Paul Ryan. (O’Neill even chose the Phoenix Park as the site of his 80th birthday celebration.) On St. Patrick’s Day in 2012, President Barack Obama dropped in for a surprise visit to the Dubliner, an event now commemorated with a plaque on the pub’s wall. A member of Historic Hotels of America since 2002, the Phoenix Park Hotel is truly an amazing place to stay in the nation’s capital.

-

About the Location +

Washington is among the nation’s most historic cities, having been founded more than two centuries ago by the Founding Fathers. In 1790, Congress specifically passed the “Resident Act” after James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton agreed to create a permanent national capital in the southern United States. Known as the “Compromise of 1790,” the men decided to place the future settlement somewhere in the South in exchange for the federal government paying off each state’s debt accrued during the American Revolution. George Washington—who was serving his first term as President—then carefully looked for the site of the new city in his role as the country’s President. He spent weeks searching for the perfect spot before finally settling upon a plot of land near the mouth of the Potomac River. Washington had felt that the location was in a terrific spot, for it was still roughly in the middle of the nation. Furthermore, he hoped its proximity near major seaports would further bind the emerging western states with the more established Atlantic coastline. Maryland and Virginia subsequently donated around 100 acres at Washington’s site, although Virginia would later rescind its gift in 1847.

Nevertheless, work on the capital began a year later and lasted for the duration of the decade. At the start of the project, the three federal commissioners in charge of supervising its progress decided to name the nascent settlement after the President himself. (They also named the federal district surrounding the city as “Columbia,” a feminine adaptation of Christopher Columbus’ name.) Noted French architect Charles L’Enfant spearheaded the city’s design, who presented a bold vision that featured wide boulevards and ceremonial spaces reminiscent of his native Paris. But despite L’Enfant’s grand plans for Washington, only the first iterations of the United States Capitol, the White House, and a couple other prominent governmental structures appeared at the time. Barely any other buildings stood in the city when the entire federal apparatus relocated from Philadelphia to Washington in 1800. Life in early Washington was hard, too, for its residents were constantly beset by disease, poor infrastructure, and local economic depressions. What few residents remained in the city year-round endured the worse hardships during the War of 1812, when the British notoriously ransacked the community. In fact, the British had even torched the U.S. Capitol Building, the Treasury, and the White House.

Washington did not finally start to develop into an actual city until the middle of the 19th century, after investment in its upkeep increased dramatically. While additional federal buildings—including the General Post Office and the Patent Office—first appeared in the 1830s, a wave of municipal and residential construction flourished in the wake of the American Civil War. But much of the construction was conducted under the auspices of a territorial government that initiated dozens of new buildings projects, including the development of schools, markets, and townhouses. Streets were also paved for the first time, while modern sanitation systems were created for the many new neighborhoods debuting throughout the city. Congress even contributed to the local construction, especially after the territorial government bankrupted itself right after its founding. But the federal government had also created some of the city’s most iconic structures on its own around the same time, such as the Washington Monument, the National Mall, the Library of Congress complex, and a new U.S. Capitol Building. The climax of all this construction work materialized with the Senate Park Commission—remembered more commonly as the “McMillan Commission”—which offered a comprehensive series of plans to beautify the entire city.

It would take years to complete the recommendations of the McMillan Commission, though. Buildings and landscape designs that reflected the commission’s research appeared throughout the first half of the 20th century, especially once the federal government became more involved in international affairs after World War I. Dozens of art galleries, storefronts, and restaurants proliferated, transforming Washington into one of the nation’s most esteemed cultural capitals. Many embassies also opened within the city along Massachusetts Avenue, giving rise to its iconic area of Embassy Row. Dozens of new monuments appeared throughout Washington, as well, such as the iconic Lincoln Memorial. Some of the most significant construction transpired during the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, which helped spur the creation of an official U.S. Supreme Court building, The Pentagon, and the famous Federal Triangle. Washington nonetheless fell into a brief period of decline around the start of the Cold War that was only reversed with the committed efforts of Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Today, Washington is now among the most powerful cities in the world, as well as one of its most gorgeous. Thousands of people from all over flock to the city each year to take in its prestigious culture and heritage.

-

About the Architecture +

The Phoenix Park Hotel itself stands as a brilliant example of Georgian Revival-style architecture. Georgian Revival-style architecture itself is a subset of a much more prominent architectural form known as “Colonial Revival.” Colonial Revival architecture today is perhaps the most widely used building form in the entire United States. It reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to the aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America’s disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country’s formative years. As such, structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture—as well as the Georgian Revival-style—featured such components as pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined their façades, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, too. This form remained immensely popular for years until largely petering out in the late 20th century.

-

Famous Historic Events +

Good Friday Agreement (1998): Also known as the Belfast Agreement, the Good Friday Agreement brought an end to nearly three decades of civil war in Northern Ireland. Starting in the 1960s, antagonism between the region’s Protestant majority and Roman Catholic minority had intensified. Fanning the tension were opposing viewpoints between those two groups regarding the fate of Northern Ireland. Protestants largely wished for Northern Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom, while the Catholics generally wanted the area to join the Republic of Ireland. This animosity finally erupted into outright violence after the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association organized against rising discrimination toward Catholics in 1969. Rioting swept through later that summer, where the Protestants clashed with the demonstrators. The following years saw a series of ongoing reprisals from paramilitary organizations, which fought to gain supremacy in Northern Ireland. The British military eventually got involved to try and quell the unrest, but it was clear that their presence only served to further inflame the situation. (Catholic nationalists discovered incidents of clandestine British support for loyalist paramilitary groups.) Sadly, more than 3,500 were killed in the ongoing conflict, many of them civilians. Even though most of the fighting occurred in Ireland itself, some violence did spill over into England and mainland Europe.

By the mid-1990s, dignitaries from Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and the British government yearned for a peaceful resolution. In 1994, all sides agreed to a temporary ceasefire, during which they could explore possible solutions. Negotiations then commenced and a general agreement began to take shape. One person who played an integral role was an American Senator named George Mitchell. Appointed as the United States Special Envoy for Northern Ireland by President Bill Clinton, officials in Ireland and the United Kingdom invited Senator Mitchell to serve as a neutral mediator. He subsequently held talks on both sides of the Atlantic, even hosting informal discussions in the Dubliner—the Irish-inspired pub located inside the Phoenix Park Hotel. The talks that Senator Mitchell arranged helped bring about the creation of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Representatives from all the parties met in Belfast on April 10—Good Friday—where they agreed to restore self-government in Northern Ireland through an entity known as the “Northern Ireland Assembly.” While Northern Ireland would remain in the United Kingdom, the assembly was empowered to govern affairs in the region independently. Furthermore, it would be run by a coalition of unionists and nationalists, guaranteeing that power would be shared equally. Officially ratified via a popular referendum in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, the Good Friday Agreement has maintained the peace ever since.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Tip O’Neill, 47th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives (1977 – 1987)

Ted Kennedy, U.S. Senator from Massachusetts (1962 – 2009)

Bill Clinton, 42nd President of the United States (1993 – 2001)

Barack Obama, 44th President of the United States (2009 – 2017)