Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover the InterContinental Chicago Magnificent Mile with its eclectic design, including a golden Moorish dome and ballroom - also decorated with Middle Eastern flourishes.

InterContinental Chicago Magnificent Mile, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2011, dates back to 1929.

VIEW TIMELINE

Discover the History of the InterContinental Chicago Magnificent Mile

Go inside this magnificent building and explore the long and colorful history of one of Chicago's favorite luxury hotels.

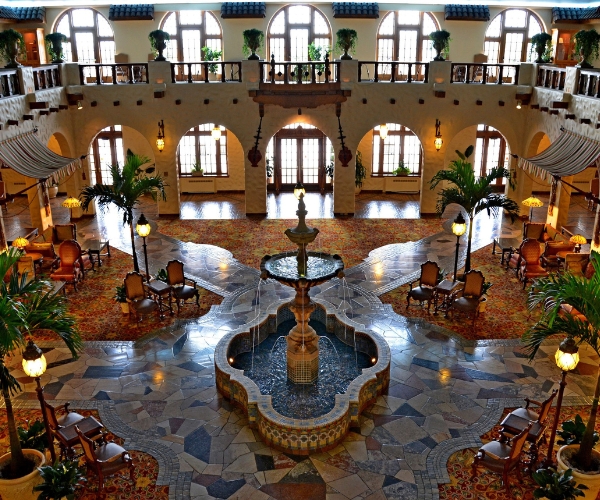

WATCH NOWOccupying a prominent place in Chicago’s Michigan-Wacker Historic District, the InterContinental Chicago Magnificent Mile has been a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2011. While this spectacular building is now one of Chicago’s most respected hotels, it was once known as the “Medinah Athletic Club.” Indeed, it was originally designed by the Shriners Organization to serve as the future gathering place for the club’s 3,500 members. Sparing no expense, the group subsequently hired the renowned architect Walter W. Ahlschlager to spearhead the building’s design. Ahlschlager proceeded to craft a magnificent 32-story skyscraper that displayed an eclectic mixture of diverse architectural forms. For instance, the massive, elliptical Grand Ballroom contained a myriad of Egyptian and Greek aesthetics, as well as a 12,000-pound Baccarat chandelier that hung over the center of the space. Further up on the eighth floor, an Indiana limestone facade was decorated by three large relief carvings that resembled ancient Assyrian motifs. And the building’s exotic gold dome—which was Moorish in influence—was developed as part of a decorative docking port for dirigibles. Ahlschlager even installed an ornate Olympic-sized swimming pool that contained a wealth of Mediterranean-inspired architecture. Indeed, the pool’s most iconic features were blue Spanish majolica tiles and a terra-cotta fountain that resembled the Roman god Neptune!

Nevertheless, the new skyscraper was criticized by many for its “wasteful extravagance” when it finally opened in 1929. Its critics specifically cited the sheer number of amenities that club members encountered upon entering, which included a miniature golf course—complete with water hazards—a shooting range, a billiards hall, a gymnasium, an archery range, a bowling alley, a two-story boxing arena, and a few hundred lavish accommodations. The supposed “decadence” of the new Medinah Athletic Club suppressed interest among club members for some time, with only a third of the guestrooms occupied in the months after its grand debut. Making matters worse, the Shriners Organization eventually filed for bankruptcy and lost their beloved new clubhouse in 1934. But the former Medinah Athletic Club was fortunately revitalized into the “Continental Hotel and Town Club” a decade later, thanks to the efforts of real estate developer John J. Mack. The public attitudes that had once plagued the building’s formative years had waned by this point, too, which enabled its new owner to successfully market its luxurious character to affluent travelers. As such, the Continental Hotel and Town Club quickly emerged as a cherished holiday destination in downtown Chicago that attracted all kinds of upscale travelers. One such famous patron was the legendary actress Esther Williams, who was often seen swimming swam laps inside the building’s famous pool.

After operating as part of both the Sheraton and Radisson corporations, InterContinental Hotels and Resorts acquired the hotel outright in 1989. The company subsequently began an extensive renovation that brilliantly restored the building back to its former glory. During that time, a former Medinah Club member heard of the renovation and donated an anniversary yearbook entitled The Scimitar. Their donation proved to be invaluable, as it was filled with photographs that would serve as the main reference point for much of the work. Many of the inner walls above the eighth floor were restructured to expand the size of the guestrooms, while on the ninth floor, the floor was raised by two-and-a-half feet to accommodate plumbing for even more accommodations. In addition to the guestroom modifications, the balcony of the Grand Ballroom—which had long since been removed—was rebuilt to match its first design. The murals and gold leaf detailing on the room’s ceiling were restored by Lido Lippi, the same man who consulted on the restoration of the Sistine Chapel. Inside the public areas, designers used painstaking attention to detail. Photographs of the original carpeting were enlarged and used to recreate its exact pattern, even making sure not to incorporate more colors than were available from the original manufacturer. Reopening as the “InterContinental Chicago Magnificent Mile” in 1990, the building quickly reemerged as one of the best hotels in Chicago. It continues to be a world-renowned destination that embraces both contemporary tastes and the elegance of the past.

-

About the Location +

Long before it would become the heart of downtown Chicago, Michigan Avenue was once just an ordinary city thoroughfare. Originally known as “Pine Street,” the road only ran the length of the Lake Michigan shoreline from the city’s southern border to the Chicago River when it first debuted in the mid-19th century. Nevertheless, some areas of Pine Street were among the best places to live in the entire metropolis, with dozens of beautiful manors and townhouses lining long sections of the road. A few municipal structures also opened, too, specifically warehouses and factories. Among the most iconic city structures built were a gorgeous water tower and pumping station. Sadly, much of Pine Street was destroyed amid the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, save for a couple historic structures (like the iconic water tower). It would not be until two architects named Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett submitted plans for the city’s complete renovation that Pine Street’s potential redevelopment became a real possibility. At the behest of the Commercial Club of Chicago, both Burnham and Bennett began devising a series of integrated projects that ultimately sought to improve Chicago’s waterfront and downtown core. One of the particular regions of Chicago that attracted their attention was the dilapidated Pine Street. Burnham and Bennett specifically called for its rehabilitation into a sprawling center of local commerce. They envisioned many ornate buildings straddling the revived Pine Street, which would be filled with all kinds of storefronts and offices spaces. Furthermore, they called for Pine Street to be widened considerably, in order to grant access to the new forms of mass transit that were now proliferating throughout Chicago. While local business leaders formed the Greater North Michigan Avenue Association as a way to fund the plan in 1912, actual construction along Pine Street did not truly commence until the onset of the Roaring Twenties.

By this point, a massive boom in commercial building projects was transpiring all over the Chicago shoreline, with Pine Street becoming one of the main focal points for the construction. Transformed into a new sprawling boulevard called “Michigan Avenue,” many kinds of new structures appeared along the revitalized corridor that displayed an amazing breadth of architectural styles. Some of Chicago’s most iconic landmarks debuted along Michigan Avenue, including Tribune Tower, the Women’s Athletic Club, and the Wrigley Building. Engineers even connected the thoroughfare to the rest of Chicago by way of the double decked DuSable Bridge. Unfortunately, the onset of the Great Depression abruptly brought an end to the work occurring all over Michigan Avenue. Construction would only resume due to the efforts of another noted Chicago-based real estate developer named Arthur Rubloff. In 1947, Rubloff specifically launched a targeted campaign to reignite the creation of ornate skyscrapers through his affiliation with the Greater North Michigan Avenue Association. He even sponsored a brilliant series of plans presented by the renowned architectural firm Holabird & Root to craft many new outstanding structures. But perhaps the most telling legacy of Robloff’s was the moniker he bestowed upon the revitalized thoroughfare. Upon witnessing the wealth of gorgeous buildings that had appeared along the avenue, he decided to christen the location as the “Magnificent Mile.” The building projects continued unabetted for many years thereafter, in which they constructed such renowned landmarks as the celebrated John Hancock Center. Michigan Avenue has since remained a fixture in downtown Chicago, attracting countless visitors each year due to its wide variety of upscale storefronts, eloquent restaurants, and fascinating cultural attractions.

-

About the Architecture +

Celebrated architect Walter W. Ahlschlager created the future InterContinental Chicago Magnificent Mile at the behest of the Shriners Organization. Ahlschlager’s subsequent eclectic design for the building incorporated elements of many different architectural styles, including motifs that harkened back to antiquity. For instance, Ahlschlager’s team incorporated a variety of ancient Assyrian relief carvings throughout the building’s limestone façade, specifically the stonework featured on the eight floor. (According to the sculptor who crafted the moldings, George Unger, the panels conveyed an artistic interpretation of “Wisdom,” “Concentration,” and “Contribution.”) Ahlschlager also incorporated Moorish aesthetics into the building’s appearance, namely the design for the gorgeous golden dome that sat atop its roof. Constructed as a possible dirigible docking port, the dome featured a wealth of gorgeous structural elements. Ahlschlager specifically placed a beautiful glass cupola inside the dome, as well as a spiral iron staircase that resembled the kind one would find in a historical lighthouse. But Ahlschlager made liberal use of various architectural styles all over the main structure’s layout, too. One of the most noteworthy places that showcased his eclectic approach was the spectacular two-story Grand Ballroom. Located on the eighth floor, it displayed a masterful blend of historic Egyptian, Greek, and Mesopotamian architecture. Perhaps its most fascinating feature was the gorgeous 12,000-pound Baccarat chandelier that hung in the center of the space. Ahlschlager installed additional unique details throughout a spectacular, Olympic-sized pool that he constructed on the 13th floor. Indeed, the pool’s most iconic features were blue Spanish majolica tiles and a terra-cotta fountain created in the likeness of the Roman god Neptune. All in all, it cost the Shriners Organization a stunning $8 million to complete!

The building underwent many renovations over the following years, especially once it became a full-fledged hotel during World War II. In 1961, for example, Sheraton Hotels developed a second complex that created many new guestrooms for the structure. This section operated as the northern wing of the hotel until it was separated as its own business unit some two decades later. Nevertheless, the most comprehensive renovation took place when InterContinental Hotels and Resorts acquired the site in 1989. During that time, a former Medinah Club member heard of the work and donated an anniversary yearbook entitled The Scimitar. Their donation proved to be invaluable, as it was filled with photographs that would serve as the main reference point for much of the work. Many of the inner walls above the eighth floor were restructured to expand the size of the guestrooms, while on the ninth floor, the floor was raised by two-and-a-half feet to accommodate plumbing for even more accommodations. In addition to the guestroom modifications, the balcony of the Grand Ballroom—which had long since been removed—was rebuilt to match its first design. The murals and gold leaf detailing on the room’s ceiling were restored by Lido Lippi, the same man who consulted on the restoration of the Sistine Chapel. Inside the public areas, designers used painstaking attention to detail. Photographs of the original carpeting were enlarged and used to recreate its exact pattern, even making sure not to incorporate more colors than were available from the original manufacturer. Initially, workers utilized a process called cornhusk blasting to strip away the many layers of paint from the marble walls in the Hall of Lions, as traditional sandblasting would have destroyed the intricate details of any etchings beneath. When it was determined that a single marble column would require close to a ton of ground corn cobs, restorers decided to scrub away the paint by hand. The project eventually concluded after a few months, with the building reborn as the “InterContinental Chicago Magnificent Mile.”

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Esther Williams, renowned swimmer and actress best remembered for her role Million Dollar Mermaid.