Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Discover Hotel Indigo Baltimore Downtown, which was once home to Baltimore’s revered Central YMCA facility for generations.

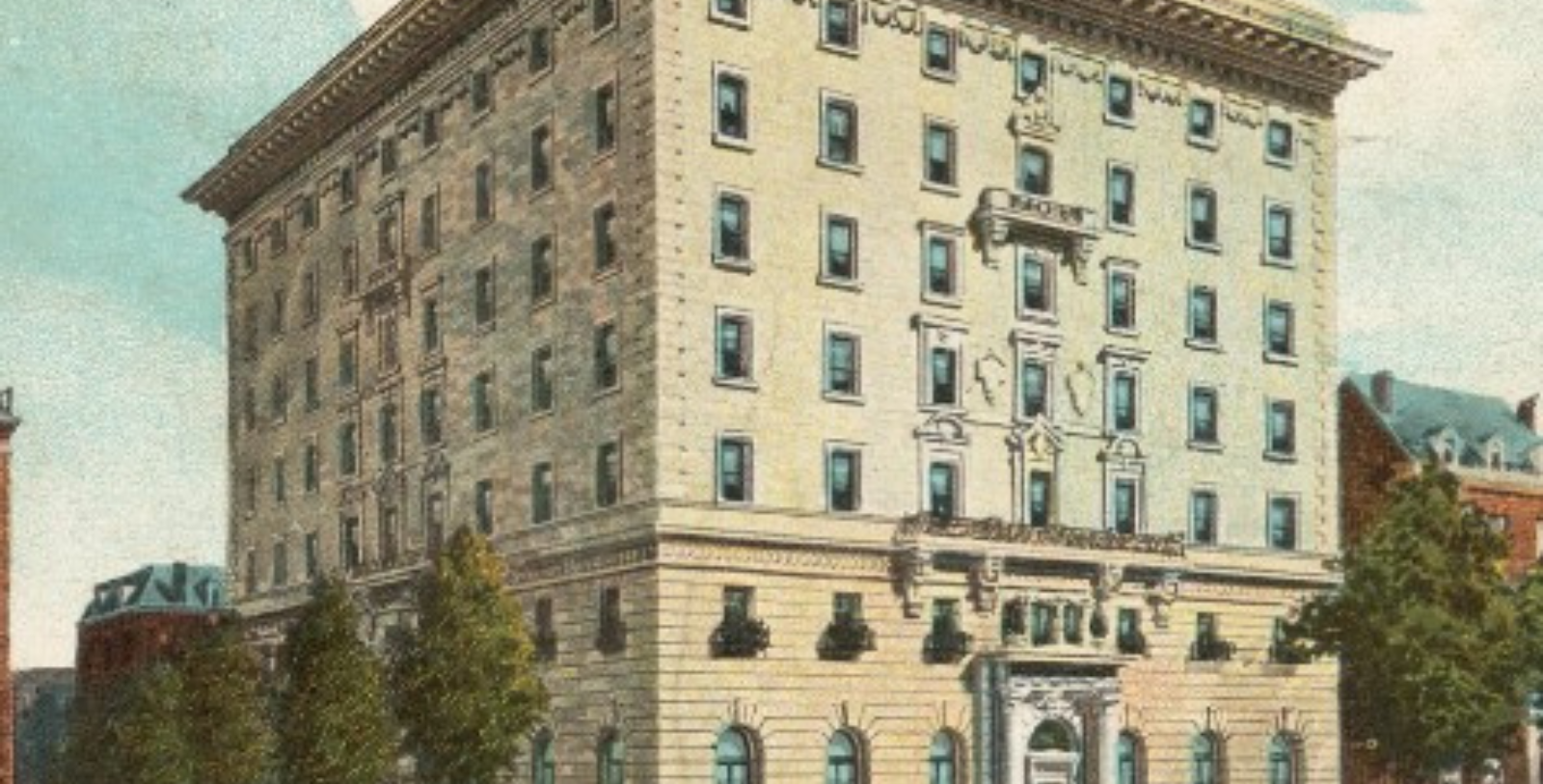

Hotel Indigo Baltimore Downtown, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2024, dates back to 1907.

VIEW TIMELINEGreat cultural changes were rapidly affecting Baltimore in the latter half of the 19th century. Already an established seaport, the metropolis had begun to receive greater volumes of trade following the debut of the historic Baltimore and Ohio Railroad earlier during the 1830s. Copious quantities of goods were now passing through Baltimore at an unprecedented rate, such as canned foods and farm fertilizers. This development spawned widespread industrialization throughout the city, leading to the creation of numerous warehouses and factories across its landscape. Countless immigrant workers were soon moving to the area in consequence, many of whom originated from rural places far away from Baltimore. Amid the drastic socioeconomic shifts, a group of likeminded Baltimoreans grew steadily more concerned for the general welfare of those new people arriving in the city. Worrying they lacked an effective social support network, the philanthropists sought out ways to create a charitable organization capable of providing basic care. The group found inspiration in the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), a British youth organization that endeavored to provide healthy activities for London’s young, working-class men. Adapting its model, the Baltimoreans subsequently chartered their own YMCA establishment within the city’s Cathedral Hill neighborhood in 1852. Among the first to open in the country, their facility—the “Central YMCA Building”—offered a host of recreational, educational, and religious services to Baltimore’s growing urban population.

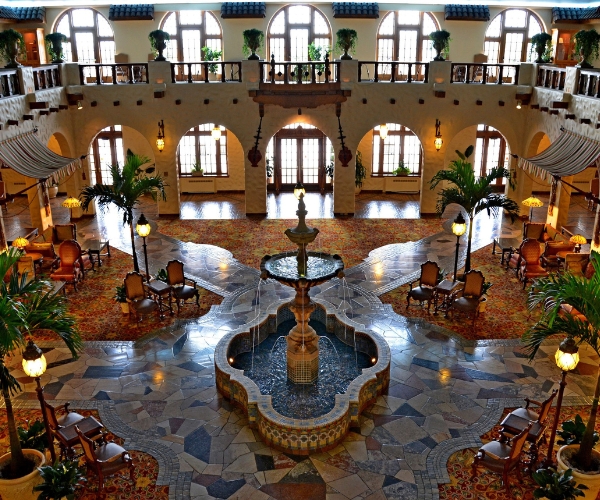

Much to the delight of the Baltimore YMCA’s founders, the facility established itself as a communal fixture within just a handful of years. In fact, this popularity remained so strong that the Central YMCA Building had come to outgrow its original location by the beginning of the 20th century. The Baltimore YMCA thus decided to create an even larger facility a few blocks away near the Baltimore Basilica. The organization then collaborated with respected local architect Joseph Evans Sperry, who in turn designed a stunning seven-story building that dominated the local skyline. (Sperry was then one of Baltimore’s best architects, having designed renowned edifices like the Equitable Building, the Provident Savings Bank Building, and the Bromo Seltzer tower.) Gorgeous architectural motifs derived from the Italian Renaissance defined its terracotta and brick façade, while many dozens of spectacular venues appeared inside, like classrooms, meeting rooms, and even a dormitory. The structure’s most impressive sections housed its health amenities, such as an exercise track, a swimming pool, and a sprawling gymnasium. Building contractor Morrow Brothers then oversaw the design's implementation, with construction starting in 1907. Taking a single year to complete, the new Central YMCA Building quickly resumed its predecessor’s status as one of the most popular civic centers in the community. Indeed, the building would go on to entertain hundreds of guests over the next seven decades!

Nevertheless, the Baltimore YMCA eventually determined that the second Central YMCA Building had become too dated during the 1980s. Leaving the structure vacant, the historic Central YMCA Building sat dormant until new owners transformed it into a hotel around the end of the decade. A corporation named “MVH Baltimore, LLC,” then acquired the structure several years later with plans to incorporate it within InterContinental Hotel Groups’ upscale Hotel Indigo brand. Spearheading a tremendous multimillion-dollar renovation, MVH Baltimore strove to revitalize the hotel’s wonderful amenities to offer luxurious service and refined elegance. However, the corporation also worked hard to preserve the rich architectural integrity of the location, investing heavily to ensure that its visual past remained intact for future generations to appreciate. (Impressively, much of the construction had even restored the building’s many intricate details, such as its beautiful dentil cornices and floral medallions.) Debuting as the “Hotel Indigo Baltimore Downtown” in 2015, this terrific historic site now thrives as one of Baltimore’s best holiday destinations. Cultural heritage travelers have come to adore the building due to its amazing past and masterfully protected architecture. Guests today are certain to enjoy the fantastic legacy left behind by the Baltimore YMCA whenever visiting the Hotel Indigo Baltimore Downtown.

-

About the Location +

In 1702, the colonial General Assembly of Maryland decided to create the “Port of Baltimore” several miles to the south of the present-day Aberdeen Proving Grounds. The politicians had hoped that a proper deep-water port on the Chesapeake Bay would give the nearby tobacco plantations and farms an easily accessible harbor from which to ship their products. The colonial administration then chartered a town around the port in honor of George Calvert, the 1st Lord Baltimore and founder of Maryland Colony. Called “Baltimore,” the settlement’s growth remained slow though, numbering only two dozen homes by the 1750s. However, everything changed when Dr. John Stevenson became incredibly wealthy upon shipping his own flour from Baltimore to customers in Ireland. Many industrialists quickly sought to emulate Dr. Stevenson’s success, building their own wharves and warehouses along the shoreline within just a handful of years. This great economic activity subsequently elevated Baltimore into the dominant economic force throughout the greater Chesapeake Bay region. Its commercial prowess had remained so strong that the British even attempted to capture the port amid the American Revolutionary War. But despite Great Britain’s imposing blockade, numerous smugglers still managed to elude the roaming hostile naval vessels that routinely patrolled the mouth of the bay. Thanks to their dedicated efforts, the community recovered swiftly once the conflict had ended. Indeed, the Maryland legislature was empowered to formally incorporate it—as well as the nearby towns of Fells Point and Jonestown—as the “City of Baltimore.”

Nevertheless, Baltimore’s emerging status as a hub for trade and commerce eventually made it a British military target yet again during the War of 1812. After Great Britain had successfully occupied the District of Columbia in 1814, Rear Admiral George Cockburn sailed a massive flotilla north to seize Baltimore’s thriving seaport. Arriving in the middle of September, Admiral Cockburn, and his ally—Major General Robert Ross—then tried to invade the city in what became remembered as the “Battle of Baltimore.” In response, the residents hurriedly erected a series of imposing fortifications all over the area. Most of their entrenchments linked up with Fort McHenry, located at the mouth of Baltimore Harbor. On September 12, British soldiers under General Ross finally attacked the city by foot, driving the American militia back into their breastworks. Admiral Cockburn then began a savage naval bombardment the following day that lasted for 25 hours. But Admiral Cockburn and General Ross failed to secure Fort McHenry’s surrender, much to the amazement of Baltimore’s citizens. Deeming the bastion to be too dangerous to capture, both men quietly left the region in defeat. The unexpected victory galvanized the country in turn, with American lawyer Francis Scott Key—who had watched the entire battle as a captive onboard a British warship—going as far as to author a poem in its memory called, “Defense of Fort M’Henry.” Decades later, Scott’s verses would become the lyrics to America’s national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner.

Baltimore remained an important economic center as the century progressed, aided in part by the development of such renowned projects as the historic National Road and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. This prosperity continued to be present during the 20th century, too, with its port routinely ferrying a diverse array of goods. But Baltimore had also emerged as a major manufacturing center, as countless factories had opened across the city that produced all kinds of products like textiles, fertilizers, and machine parts. World War II played an especially prominent role toward solidifying the city’s transformation into a thriving industrial site, as businesses across Baltimore created everything from gas masks to jeeps. In fact, one company—Martin-Marietta—even specialized in producing enormous quantities of the U.S. Army Air Force’s famed B-26 and B-29 bombers!

-

About the Architecture +

When architect Joseph Evans Sperry first designed the Central YMCA Building, he chose Renaissance Revival-style architecture as the source of his inspiration. In fact, he specifically focused on the architectural motifs of the Italian Renaissance, namely the palazzos developed in Tuscany around that time. Italian Renaissance Revival architecture itself is a subset of a much larger group of styles known simply as “Renaissance Revival.” Also referred to occasionally as “Neo-Renaissance,” Renaissance Revival architecture is a group of architectural revival styles that originally date back to the 19th century. Neither Grecian nor Gothic in appearance, Renaissance Revival-style architecture drew inspiration from a wide range of structural motifs found throughout Early Modern Europe. Architects in France and Italy were the first to embrace the artistic movement, who saw the architectural forms of the European Renaissance as an opportunity to reinvigorate a sense of civic pride throughout their communities. Those intellectuals incorporated the colonnades and low-pitched roofs of Renaissance-era buildings into their designs, along with the characteristics of Mannerist and Baroque-themed architecture. The greatest structural component to a Renaissance Revival-style building involved the installation of a grand staircase in a vein like those located at the Château de Blois and the Château de Chambord in France’s Loire Valley. This feature served as a central focal point for the design, often directing guests to a magnificent lobby or exterior courtyard further inside. But the nebulous nature of Renaissance Revival architecture meant that its appearance varied widely across Europe and North America. Many architects thus left their own mark upon any structure designed with Renaissance Revival-style design aesthetics, including Joseph Evans Sperry. Historians thus often find it difficult to provide a specific definition for the architectural movement, yet acknowledge its inherent beauty, nonetheless.