Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

Hilton Richmond Downtown, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2024, dates to 1885.

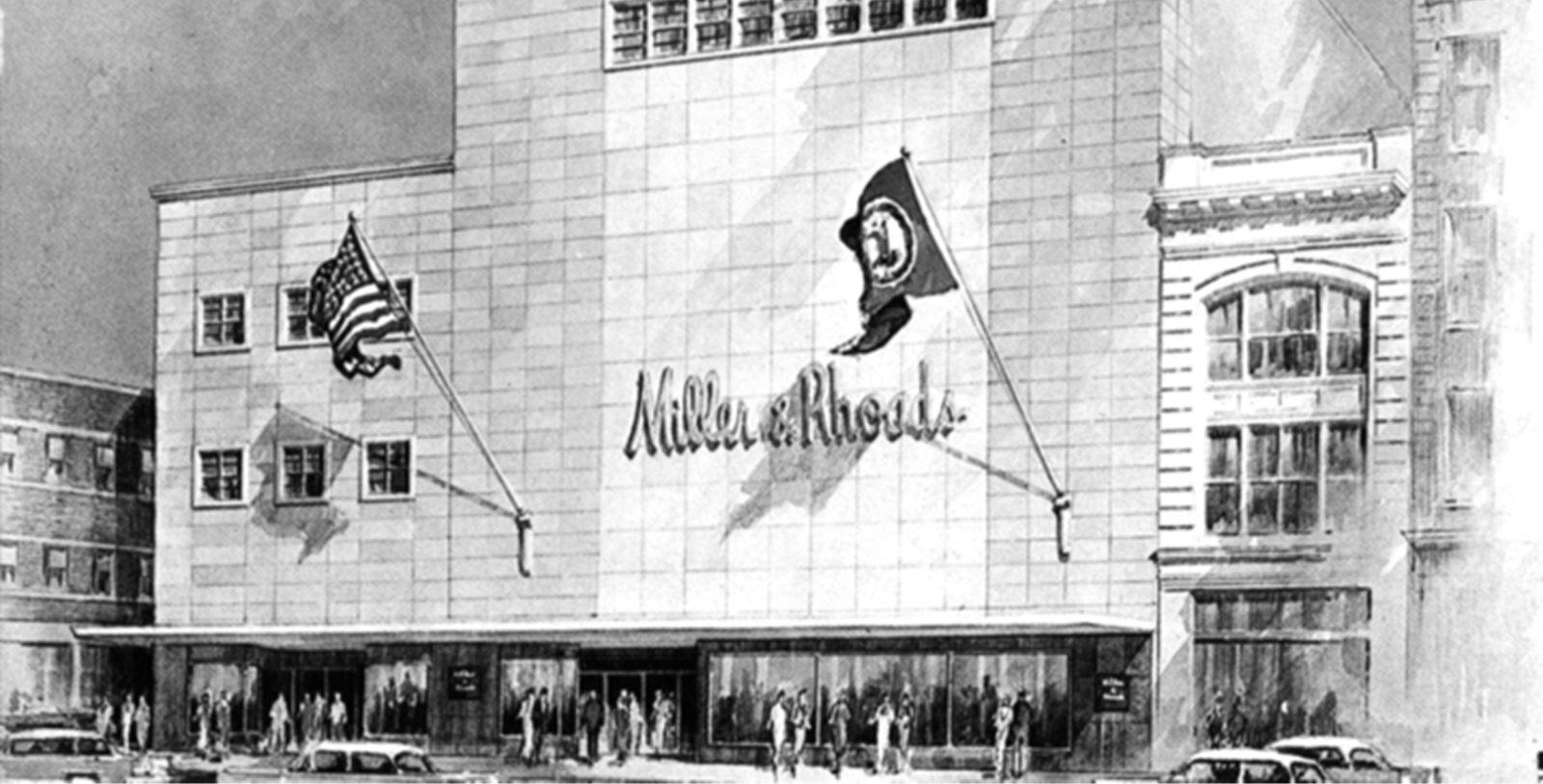

Discover Hilton Richmond Downtown, which was once the flagship location for the nationally esteemed Miller & Rhoads department store.

VIEW TIMELINEIn the wake of the American Civil War, three Pennsylvania-based entrepreneurs named Linton Miller, Webster Rhoads, and Simon Gerhart opened a dry-goods store in downtown Richmond, Virginia. Referring to the enterprise as the “Miller, Rhoads, & Gerhart” company, the businessmen had hoped that their storefront would attract the attention of merchants who were then working toward reviving the city’s economic fortunes. They debuted their nascent shop together during the mid-1880s, which quickly emerged as a prominent fixture throughout the local community. The Miller, Rhoads, & Gerhart store became inundated with countless customers, making the firm one of the most lucrative operations in Richmond. The company had generated such considerable earnings that the three partners were motivated to seek accommodation within a larger facility a couple of years later. Miller, Rhoads, and Gerhart opted to purchase a commercial compound a few blocks away from their earlier location, specifically selecting a beautiful structure along the city’s booming Broad Street. The move proved to be an incredibly wise investment, as the clientele immediately took to the additional space that the second site afforded. Although Gerhart ended his involvement not long thereafter, the company—now known more simply as just “Miller & Rhoads”—continued to grow in both popularity and profitability. Miller and Rhoads were able to expand the scale of their thriving business, eventually relaunching it to function as a massive department store in the early 20th century.

The Miller & Rhoads shop had been significantly transformed, gradually coming to cover the entire neighborhood block upon which it resided. Webster Rhoads decided to commission a comprehensive renovation in the 1920s, intending for the building’s reimagined appearance to better represent the rising level of luxury goods that the Miller & Rhoads department store had started to sell. (For reference, Linton Miller had died during the decade prior.) The renowned architectural firm Starrett & VanVleck spearheaded the project, going on to reshape the exterior façade to showcase the finest Art Deco design aesthetics of the age. The success of Miller & Rhoads continued for many decades, managing to withstand the harsh economic realities of the Great Depression and World War II. The middle of the century saw the company reach the highest heights of its prosperity, having come to serve as the city’s main shopping center by the 1950s. All kinds of distinctive products were on display inside the store, ranging from rare beauty products to posh designer clothing. A fine dining establishment debuted on the top floor called the “Tea Room,” which featured signature menu items like the Missouri Club sandwich, Brunswick stew, and a delectable Miller & Rhoads-branded chocolate cake. The appeal of the department store had become so significant that it began attracting shoppers from the whole Mid-Atlantic region, who would arrive on special weekend trips to explicitly experience its wares!

In fact, the company’s corporate leadership team eventually felt empowered to evolve Miller & Rhoads into a regional chain, opening several more affiliated retailers in multiple cities across the commonwealth. A series of poor management decisions began to undermine the stability of the business, leading to its bankruptcy in 1990. But while some of the satellite stores survived as part of other national corporations, the original flagship Miller & Rhoads site in Richmond was abandoned. Its future bleak, the structure fortunately received a new lease on life when enterprising hoteliers acquired the complex during the early 21st century. Intent on reviving it as a beautiful hotel, the group went about remolding the interior layout to host a brilliant array of modern guestrooms and meeting facilities. However, the owners also endeavored to protect the building’s history, diligently safeguarding the preexisting architecture to highlight its past as the once prestigious Miller & Rhoads department store. After months of arduous work, the iconic landmark finally reopened triumphantly as the “Hilton Richmond Downtown” in 2006. Recently renovated yet again, this fantastic holiday destination has remained one of the finest places to visit in the heart of Richmond. Cultural heritage travelers have adored discovering the hotel’s fascinating heritage, as its leadership team has remained steadfast in its commitment to commemorate the importance of the former Miller & Rhoads compound. Thanks to their enthusiastic efforts, the legacy of this terrific historic site will endure for generations to come.

-

About the Location +

Toward the beginning of the 18th century, the site of present-day Richmond was known among the Virginia colonists for its strategic location along the James River. Settlement had remained sparse though, consisting of only a few dozen Euro-American families. But the area's fate changed dramatically after the Warehouse Act passed by the Virginia House of Burgess in the early 1730s. The legislation specifically called for the inspection of tobacco cultivation, then Virginia’s most lucrative industry. Prominent planter William Byrd II thus began to construct one of the depots close to his estate, leasing a sizeable tract of land for the creation of an accompanying town. Work on Byrd’s new community began in earnest in 1737, with civil engineer William Mayo laying out the original street grid. Byrd subsequently called his new town “Richmond” in honor of Richmond, England, as they both enjoyed similar landscapes. Richmond remained small despite its significant role in Virginia’s colonial economy, hovering around a couple hundred residents on the eve of the American Revolution. The community was at the forefront of the movement once it started across the Thirteen Colonies in the 1770s.

Among the most prominent events to occur within the town was Patrick Henry’s famous “Give me liberty, or give me death” speech at St. John’s Church, which historians often cite as one of the American Revolution’s most memorable moments. Virginia politicians sympathetic to the Patriot cause gradually met in Richmond afterward, leading to its designation as the new state capital in 1780. But its rich affiliation with the revolutionaries made it a target for the British military. Notorious American turncoat Benedict Arnold even led a raid on Richmond, forcing the state government—including then-governor Thomas Jefferson—to temporarily flee deeper into the Virginian interior. Richmond nonetheless recovered from the attack, going on to emerge as one of Virginia’s leading municipalities in the wake of the American Revolution. In fact, Richmond started to industrialize in the early 19th century, thanks to the debut of the celebrated James River and Kanawa Canal. Now evolving into a full-fledged city, Richmond attracted many industrialists due to its enhanced transportation and hydropower capabilities. Perhaps the largest business to appear at the time was the sprawling Tredegar Iron Works, which produced many metallic goods for decades.

This economic activity only increased when the railroads arrived during the 1850s, namely the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad. However, this prolonged period of prosperity featured a darker side, as it was supplemented by African American slavery. The institution became a bedrock to the city’s socioeconomic identity that it eventually drove the populace to support the Southern Confederacy once the American Civil War erupted in 1861. Richmond emerged as the national capital for the Confederacy, with the historic Virginia State Capitol functioning as its main legislative building. The city’s importance within the Confederacy made its capture a vital component to the Union’s war strategy as well, causing many battles to be fought all around its borders in both 1862 and 1864. But the worst devastation occurred near the end of the war when retreating Confederate soldiers set the metropolis ablaze to prevent anything significant from falling under Union control. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln then visited the desolated city just a few days later, iconically entering the vacated Confederate capital alongside a troop of Black cavalry soldiers.

Richmond eventually reemerged as one of the most prosperous communities in the American South by the end of the 19th century. This new era of economic success continued well into the following century, which saw the city expand exponentially via a variety of infrastructural and commercial projects. Richmond still struggled with the legacies left behind by the American Civil War though, specifically the fate of its African American residents who continued to live in racial segregation. The city became a major battleground in the fight for modern civil rights as a result, with protests taking place all over the city. Among the greatest to occur were the actions taken by the “Richmond 34,” who famously staged the sit-in of a segregated lunch counter inside the Thalhimers department store. Richmond has grown to be one of the most culturally diverse communities throughout the entire country, serving as home to fascinating museums, art galleries, universities, and even Fortune 500 companies. The city is particularly noted for its wealth of historic sites that relate intimately to the American Revolution, American Civil War, and Civil Rights Movement. Cultural heritage travelers are certain to find Richmond’s past to be worth learning about.

-

About the Architecture +

The Hilton Richmond Downtown displays some of the finest preserved Art Deco architecture in Richmond. Art Deco Style is still one of the most famous architectural styles in the world, having emerged from an intellectual desire to break with past precedents. Professionals within the field aspired to forge their own design principles based on modern concepts. More importantly, they hoped that their ideas would better reflect the technological advances of the modern age. Historians often consider Art Deco to be a part of the much wider proliferation of cultural “Modernism” that first appeared at the dawn of the 20th century. Art Deco as a style first became popular in 1922, when Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen submitted the first blueprints to feature the form for contest to develop the headquarters of the Chicago Tribune. While his vision did not win over the judges, they were widely publicized. Architects in both North America and Europe soon raced to copy his form in their own unique ways, giving birth to the Art Deco movement. The international embrace of Art Deco had risen so quickly that it was even the central theme of the renowned Exposition des Art Decoratifs in Paris a few years later. Professionals the world over fell in love with Art Deco’s sleek, linear appearance, defined by a series of sharp setbacks. They adored its geometric decorations that featured such motifs as chevrons and zigzags. But despite the deep admiration people felt toward Art Deco, interest in the style gradually dissipated throughout the mid-20th century. Many examples of Art Deco architecture survive today though, with some of the best located in such places as New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles.