Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

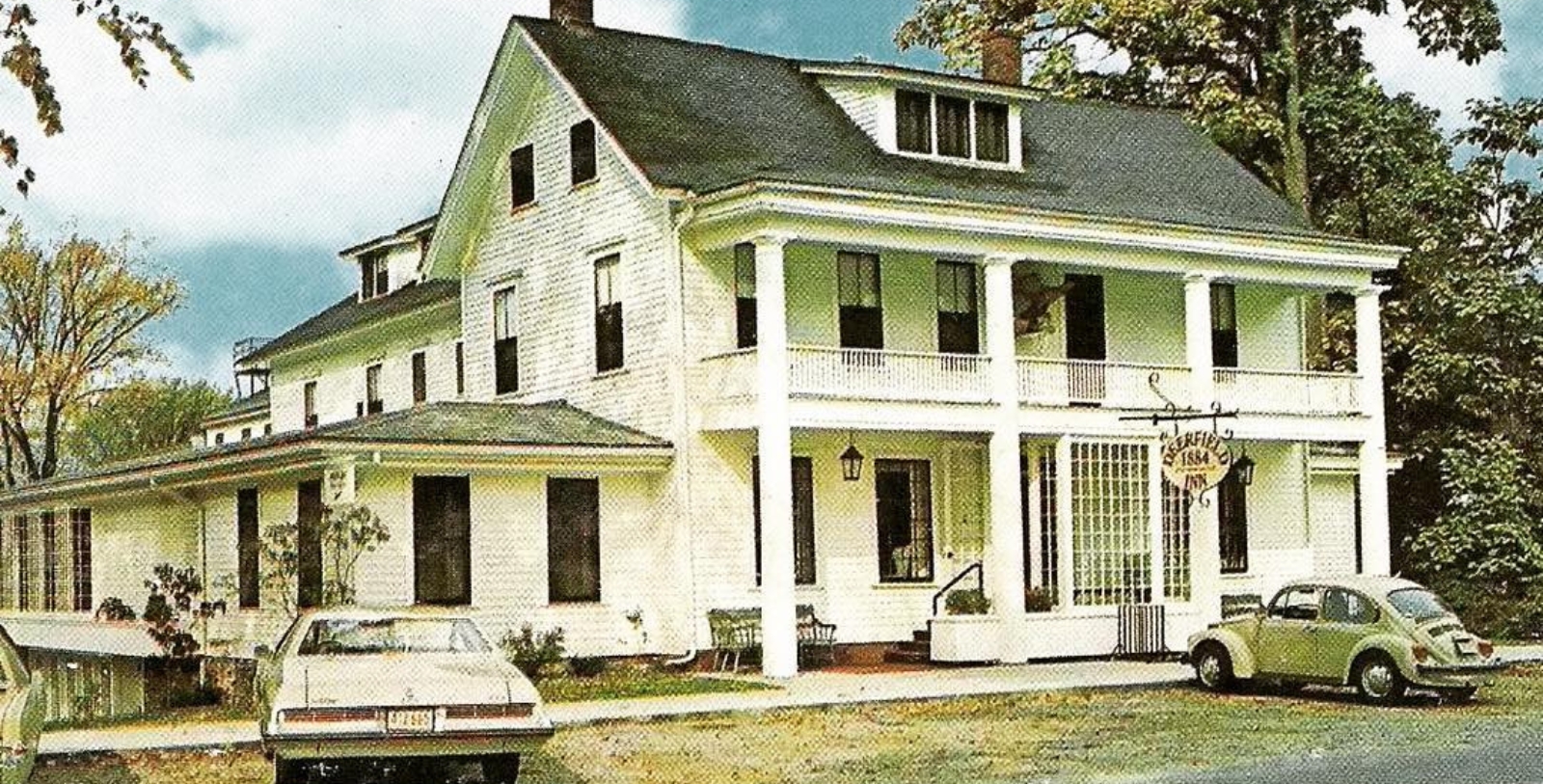

Discover Deerfield Inn, which is one of the historic structures constituting Historic Deerfield—an internationally renowned open-air museum chronicling the history of colonial America.

Situated along Old Main Street in Deerfield, Massachusetts, the Deerfield Inn stands as a living testament to New England’s enduring cultural identity. Since its opening in the late 19th century, the inn has not only offered a memorable vacation experience but has emerged as a cherished landmark within a village already deeply steeped in American history. The Deerfield Inn was originally constructed amid a time of great hardship, as a destructive series of natural disasters had befallen many of the towns lining the surrounding Connecticut River Valley. Drought and pestilence swept through most of the adjacent farmland in 1884, ruining the livelihoods of countless families across the region. Following this tragedy, brothers Edward and Frederick Everett decided to build a quaint country tavern right in the heart of their hometown of Deerfield, hoping its presence would provide a stabilizing influence on the economy. The two men envisioned the nascent building catering to the rising number of vacationers interested in exploring the surviving Colonial-era homes still standing in the settlement. Both Edward and Frederick spent the next several months overseeing the creation of the business, which they named the “Deerfield Inn” upon its completion the following year. From the start, the inn quickly proved to be more than just a place to sleep, assuming significance as an important local social gathering spot in mere weeks!

Through the following decades, the Deerfield Inn went on to welcome a diverse array of guests— artists, writers, and other intellectuals—who were drawn to the area’s fascinating heritage and pastoral beauty. The inn’s proximity to elite educational institutions including Deerfield Academy, Eaglebrook School, and Bement School made it a particularly popular destination for visiting instructors slated to teach at one of those locations. Figures of national repute eventually traveled to the Deerfield Inn, including celebrated First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt! Guests came to adore the authentic nature of the historic accommodations present on-site, such as the sprawling front porch and the cozy wintery fireplace in the parlor. Perhaps the most alluring attraction was Champney’s Restaurant. Named after renowned artist James Wells Champney—a Deerfield resident—the dining establishment had embraced the farm-to-table ethos long before it became a general trend. Despite its idyllic setting, the Deerfield Inn was not immune to the challenges of the coming 20th century. The business managed to weather such tumultuous events as the Great Depression and World War II, with its accomplished staff striving to ensure that its historic character survived for future generations to appreciate.

In 1945, the Deerfield Inn was acquired by Historic Deerfield, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the town. This partnership ensured that the inn would remain true to its roots while adapting to the needs of modern travelers. Renovations were undertaken with care, which both safeguarded the original architectural details and upgraded the amenities to meet contemporary expectations. Today, the Deerfield Inn continues to thrive as a beacon of hospitality and history, its two dozen guestrooms reflecting the town’s storied past. Visitors often find themselves immersed in the greater community of Deerfield, as the historic houses residing next to the Inn function as public museums. Also maintained by Historic Deerfield, the collection of former homes features evocative exhibits that chronicle the lives of the town’s early settlers, Revolutionary War veterans, and Native American neighbors. As it moves into its third century of service, the Deerfield Inn remains truly committed to sharing its heritage.

-

About the Location +

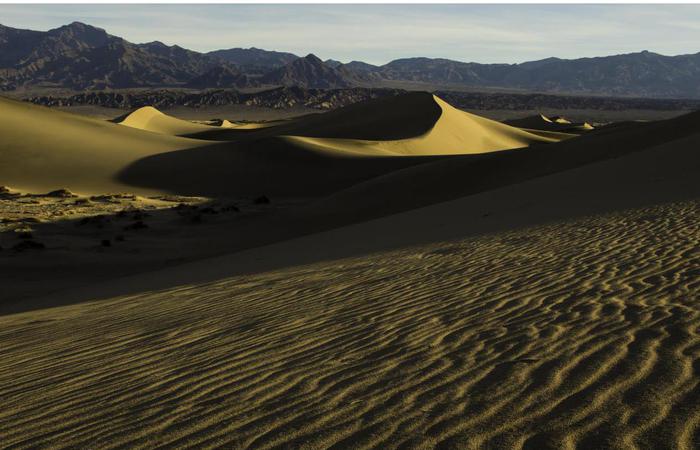

Nestled right in the middle of the verdant Connecticut River Valley, the town of Deerfield, Massachusetts, claims a deep, fascinating history that goes back centuries. The fertile meadows surrounding present-day Deerfield had originally been home to the Pocumtuck tribe. The Pocumtucks thrived in the region for generations, defending their territory against rival tribes. Then in 1667, John Pynchon, acting on behalf of the town of Dedham, purchased 8,000 acres from the Pocumtucks. This land was intended as compensation for Dedham’s residents whose property had been repurposed for colonial pastor John Eliot’s missionary work. Samuel Hinsdell became the first English settler in the area about two years later. By 1673, nearly two dozen other families had come to join Hinsdell, establishing a village that they called “Deerfield.” Life proved to be calm at first, with the inhabitants creating an agrarian community. But this tranquility was shattered when a conflict known as “King Philip’s War” erupted in 1675. Primarily fought between the English and a confederation of indigenous tribes, the war saw both sides wage pitted battles all over Massachusetts. Deerfield emerged as an outpost for the colonists, repelling attacks that came close to destroying the community.

The town suffered a tragic blow after the native forces ambushed an English relief column. Sixty-four settlers ultimately perished, and the village was temporarily abandoned. While Deerfield was reoccupied a decade later, it was almost destroyed again once fighting related to the European War of the Spanish Succession reached North America. Seeking to disrupt British military activities, the French orchestrated a daring raid from Canada in 1704. A force of more than 300 French and Native American soldiers targeted Deerfield that February. The surprise assault overwhelmed the town, resulting in its near annihilation and the forced march of over 100 Deerfielders to Canada. Despite the devastation, many former residents returned and rebuilt their community. Though peace was elusive, periodic skirmishing continued through the mid-18th century, and the village evolved into a vital center for commerce. During the latter stages of the French and Indian Wars, for instance, Deerfield often supplied wheat and meat to British armies as they made their way north. The trade proved to be prosperous, enabling Deerfield’s families to furnish their homes with elegant wares crafted locally or imported from Great Britain. But Deerfield soon became a microcosm of the mounting political strife that encompassed the Thirteen Colonies amid the buildup to the American Revolution.

Whigs and Tories clashed in homes across Deerfield, debating the merits of independence based on the events unfolding in Boston. Local men enlisted in the Continental Army seeing service at such battles as Bunker Hill and Saratoga. Meanwhile, Deerfield functioned as an integral supply depot, providing food for American soldiers Benedict Arnold—then still a Patriot—procured 15 tons of beef from Deerfield for the troops stationed at Fort Ticonderoga in 1775. Agriculture remained pivotal to the livelihoods of Deerfield’s people heading into the 19th century, particularly the raising of livestock for sale in distant urban markets. However, rising competition from the western plains gradually diminished demand for the town’s goods, forcing it to embrace a new economic identity centered on the educational institutions that had started opening around town. The first to debut was the Deerfield Academy, which weathered fluctuating fortunes before finally flourishing during the early 1900s. Alongside Eaglebrook School and the Bement School, Deerfield Academy ultimately helped Deerfield earn a reputation for providing access to some of the finest youth education in New England.

Yet, the town’s commitment to its past remained equally strong. Historian George Sheldon founded the “Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association” at the height of the Gilded Age, thus initiating a long-lasting movement to preserve Deerfield’s heritage. This preservation effort gained further momentum with the creation of the “Historic Deerfield” organization by Henry and Helen Flynt. Through the restoration of the surviving colonial-era buildings, Historic Deerfield proceeded to transform Old Deerfield into a vibrant living history museum that has continued to thrive. Historic Deerfield features an extensive variety of informative exhibitions that chronicle the lives, art, and culture of New England residents. Deerfield currently stands as one of the most successful community restorations in the United States, where history is not only remembered but actively taught. Perhaps the best symbol of this achievement has been the site’s continued designation as a rare U.S. National Historic Landmark, which the U.S. Department of the Interior bestowed during the 1960s. From its indigenous roots and colonial trials to its modern role as a beacon of historic preservation, Deerfield’s story is truly one of enduring spirit.

-

About the Architecture +

In keeping with the ambiance of Old Deerfield, the Deerfield Inn was originally designed using the stylistic vocabulary of the Colonial Revival-style. Colonial Revival architecture reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to this historically infused aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America’s disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, when people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia to commemorate the founding of the United States. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused on the country’s formative years. Structures built in the style of the Colonial Revival featured such components as pilasters, ornamental brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetry defined Colonial Revival-style façades, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used as well. This building style remained immensely popular for years. Architects today still rely upon Colonial Revival architecture, using the style to construct many kinds of residential and commercial buildings.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady of the United States (1933 – 1945)

In the 1970’s guests included:

Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward

Nelson Rockefller

Gregory Peck

Walter Cronkite

-

Women in History +

In the late nineteenth century, when the rise of manufacturing had eclipsed the markets for some of Deerfield’s agricultural goods, a series of notable women preserved the town’s fortunes. They did this by attracting tourists interested in Deerfield’s colonial roots and by fostering communities of women who learned to produce handmade goods in the Arts and Crafts style. One of the most famous women to live on the street was C. Alice Baker (1833-1909), an educator and historian with family ties to the community. Baker restored Frary House in Deerfield in 1890 and later spent summers shoring up not only the house itself but also the community in which she found herself. Baker was a meticulous researcher and worked to trace the lives of the colonists who had been captured in the 1704 raid on the town; her dramatization of the event helped to reinforce the raid’s resonance in the community across the centuries. Along with her lifelong companions Susan Minot Lane (1832-1893), a painter, and later Emma Coleman (1853-1942), a photographer, Baker made Frary House a center of community and artistic life. These women were interested in the cultural and aesthetic aspects of a particular version of colonial history that emphasized the sobriety, frugality, and ingenuity of white Protestant settlers to the area. Their historical writings, paintings, and photographs were admired in their day and constituted one part of the broader historical and artistic legacy that helped support the town into the twentieth century.

If C. Alice Baker’s exploration of Deerfield’s colonial period represented one way that the town looked to history to navigate its present, then engagement with the Arts and Crafts movement was another. The Arts and Crafts movement began in industrialized Victorian England, when artists and social reformers became concerned that mechanization and standardization not only alienated workers from the fruits of their labor but also produced goods inferior to those made by artisans of the past. The movement caught on in America, as well, and many artists and architects in Boston, Chicago, and some small towns like Deerfield became centers for artisans whose works evoked an imagined past where objects could be beautiful, natural, and individual rather than plain, artificial, and mass produced. Women like Margaret C. Whiting (1860-1946) and Ellen Miller (1854-1929) helped cement the importance of the movement in Deerfield by forming the Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework in 1896. They admired the crewelwork embroidery popular in the eighteenth century and taught several other Deerfield women the particular style of stitching so that they could replicate it on bed hangings, napkins, and myriad other linens. Whiting and Miller oversaw the women’s work to ensure quality control and paid the women who embroidered for the Society—this represented an important source of income for women who had few other ways to earn. The Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework helped expand Deerfield’s reputation as a center of production for high quality Arts and Crafts handiwork.

Another woman who evoked the past while enhancing Deerfield’s connection to cosmopolitan trends and movements was the writer and artist Madeline Yale Wynne (1847-1918). Wynne spent time in Chicago, where she helped found the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society and witnessed the work of Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr’s Hull House. She returned to New England impressed by both the Arts and Crafts movement and the settlement house movement’s model of social and educational development. In 1901 she founded the Deerfield Society of Arts and Crafts and oversaw the production of a variety of handicrafts that drew tourists whose purchases helped support the makers. Wynne was a skilled artist and metalworker herself, and a particularly exquisite example of her work—a wood and metalwork Garden of Hearts chest—is on display at Historic Deerfield’s Flynt Center of Early New England Life.

Perhaps the greatest guest to ever visit the historic Deerfield Inn was former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in the 1950s. In addition to advocating for community service and social activism while in the White House, alongside her husband Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt spoke publicly on issues such as civil rights and women’s rights. Most famously, she arranged a massive celebration at the Lincoln Memorial to protest the racist decision of the Daughters of the American Revolution to not let Marian Anderson—the African American opera singer—perform at Constitution Hall. She also worked behind the scenes, lobbying for the passage of the Costigan-Wagner Bill, which would have made lynching a federal crime. While she was not always at ease in the role of First Lady, her active participation in critical issues of her day helped contribute to Americans’ broadening of their sense of the role and the women who held it.