Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

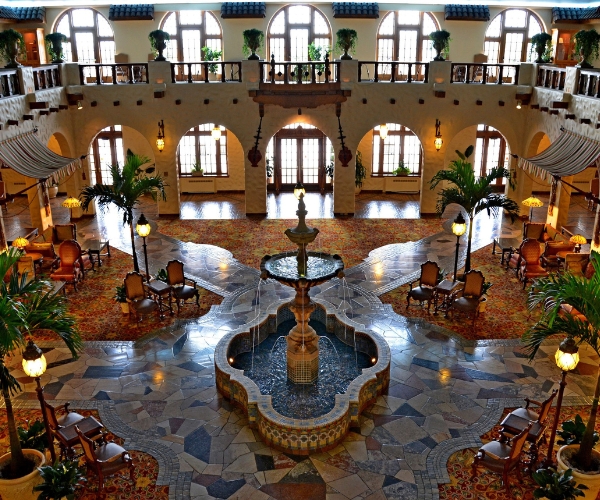

Discover Colonial Inn, which has been hosting countless guests visiting the Little Traverse Bay region since the height of the Gilded Age.

Nestled along the serene shores of Little Traverse Bay, the charming Colonial Inn has provided memorable vacation experiences for more than a century. Indeed, this quaint lakeside destination had originally debuted at the height of the Gilded Age, back when the nation’s tourists were just starting to discover the pastoral beauty of greater Lake Michigan. A Civil War veteran remembered to history as “Colonel Eaton” first opened the Colonial Inn during the 1890s, having found its bucolic setting the perfect place for achieving much needed rest and relaxation. Eaton had previously gained a prestigious military career in the Union army, serving with distinction as part of the now-famous Michigan-based Wolverine Cavalry Brigade. He had supposedly earned the praise of his colleagues for outstanding bravery and strategic acumen, which granted him a notable reputation throughout the entire unit. In the wake of the conflict, Eaton subsequently applied those qualities to a variety of business ventures, leveraging his wartime connections to eventually fund the creation of the Colonial Inn several decades later. (Oral tradition even stipulated that a portion of Eaton’s funding had origins with the ransom provided by Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ capture.) However, the Colonial Inn fulfilled a secondary purpose, as its tranquil ambiance and inviting atmosphere would grant spiritual healing to any guest who had fought in the war. Construction on the prospective retreat then began in earnest in 1894 and took several months to complete. Nevertheless, the gorgeous building soon came to display a wealth of colonially inspired architectural motifs, stirring Eaton to give the site its name.

When work on the nascent Colonial Inn finally concluded, the destination quickly emerged as one of the most popular places to visit in the region. Much of its success was due in great part to Eaton, who’s organizational and leadership skills were essential toward keeping the business running to an elevated standard. After his death in 1904, his widow continued to run the inn, displaying remarkable resilience during a time when women had limited opportunities. In fact, her management ensured the inn's continued success until the 1920s, when a German World War I officer known as “Papa Tam” became the proprietor. Then in 1955, the Colonial Inn entered a golden era under the ownership of John R. Davis—a vice president at the Ford Motor Company—and local civic leader Fred Renker. They subsequently expanded the inn exponentially, adding the East and West Plazas that enhanced the number of available guestrooms. However, the building underwent even more changes when North Carolina entrepreneur Ray Brown purchased it a decade later. Ray's tenure specifically marked a period of modernization as the inn shifted from hosting long-term summer guests to accommodating a more transient clientele. His son, Tim Brown, would go on to follow this legacy, too, and institute further renovations that preserved the structure’s historical essence. Unfortunately, Tim Brown passed away in 2016, but his vision for the inn lived on through his eldest son, Timothy P. Brown, who now owns and operates the establishment. Thanks to the continued stewardship of the Brown family, the Colonial Inn has since remained a cherished holiday destination in Harbor Springs.

-

About the Location +

Long before the first Euro American settlers ever arrived, the area that is now home to Harbor Springs was called “Waganikisi” by the migratory Odawa tribes. The Odawa would annually spend the winter months in southern Michigan, returning north each spring to hunt, fish, and plant crops. Their influence proved to be incredibly influential to the region’s very identity, as their seasonal villages came to populate the shoreline of places like Little Traverse Bay for generations. But then in the late 17th century, French Jesuits started exploring the location, granting it the name “L'Arbre Croche,” or "The Crooked Tree." (The name reflected the unique landscape of Little Traverse Bay, specifically the presence of a strange, notched tree that prominently protruded out from the surrounding canopy.) Additional French colonials subsequently followed in their wake, establishing a quaint fur-trading outpost that doubled as a small agricultural community. The permanent settlement of the French benefited the Odawa, with the two forming a mutual relationship that lasted well into the 18th century. Although the area eventually became part of France’s sprawling North American empire, the land was nonetheless absorbed by colonial British America and then the nascent United States. American pioneers in turn gradually came to supplement the preexisting population over the next several decades, turning into rugged homesteaders, loggers, and farmers. Nevertheless, the region continued to feature a small array of isolated villages throughout much of the 19th century, helping it to retain its bucolic charm and tranquil ambiance.

Among the towns to appear at the time was Harbor Springs, which was built upon the earlier French hamlet L'Arbre Croche. Due to the amazing pastoral beauty that surrounded Harbor Springs, vacationers from across the American Midwest began to visit on long weekend trips at the height of the Gilded Age. Enterprising hoteliers then started to open their own summer resorts, including Harbor Point, Wequetonsing, and Menonaqua. Indeed, travelers specifically flocked to Harbor Springs to escape the heat and enjoy activities like sailing, fishing, and socializing at the turn of the century. Now known as the “Naples of the North” across Michigan, Harbor Springs went on to thrive as a major regional center for tourism, its rustic streets lined with all kinds of outstanding hotels and boarding houses. Today, Harbor Springs continues to be an esteemed holiday destination, offering visitors access to thrilling outdoor activities, such as golfing, biking, hiking, and general sightseeing. (One of the best places to experience most of those options is the verdant, 30-acre Thorne Swift Nature Preserve, located just north of Harbor Springs.) But the town has successfully preserved its fascinating heritage, too, as many of the erstwhile Victorian-era cottages have been readapted for further use. In fact, several of those structures currently serve as renowned cultural attractions, including the Depot Club and Restaurant and the Harbor Springs Area Historical Society. From its Native American roots to its status as a beloved summer retreat, Harbor Springs truly has a unique and vibrant story that remains captivating to both residents and guests alike.

-

About the Architecture +

Colonial Inn displays a brilliant blend of Colonial Revival-style architectural motifs. Colonial Revival architecture is the most widely used building form in the entire United States. It reached its zenith at the height of the Gilded Age, where countless Americans turned to the aesthetic to celebrate what they feared was America’s disappearing past. The movement came about in the aftermath of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, in which people from across the country traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to commemorate the American Revolution. Many of the exhibitors chose to display cultural representations of 18th-century America, encouraging millions of people across the country to preserve the nation’s history. Architects were among those inspired, who looked to revitalize the design principles of colonial English and Dutch homes. This gradually gave way to a larger embrace of Georgian and Federal-style architecture, which focused exclusively on the country’s formative years. As such, structures built in the style of Colonial Revival architecture featured such components as pilasters, brickwork, and modest, double-hung windows. Symmetrical designs defined Colonial Revival-style façades, anchored by a central, pedimented front door and simplistic portico. Gable roofs typically topped the buildings, although hipped and gambrel forms were used, as well. This building form remained immensely popular for years until petering out in the late-20th century. Nevertheless, architects today still rely upon Colonial Revival architecture, using the form to construct all kinds of residential buildings and commercial complexes. Many buildings constructed with Colonial Revival-style architecture are even identified as historical landmarks at the state level, and the U.S. Department of the Interior has even listed a few of them in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.