Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

rich history of a historic castle hot springs hotel

Discover Castle Hot Springs, which was founded at the height of the Gilded Age as Arizona’s first wellness resort.

Castle Hot Springs, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2024, dates back to 1896.

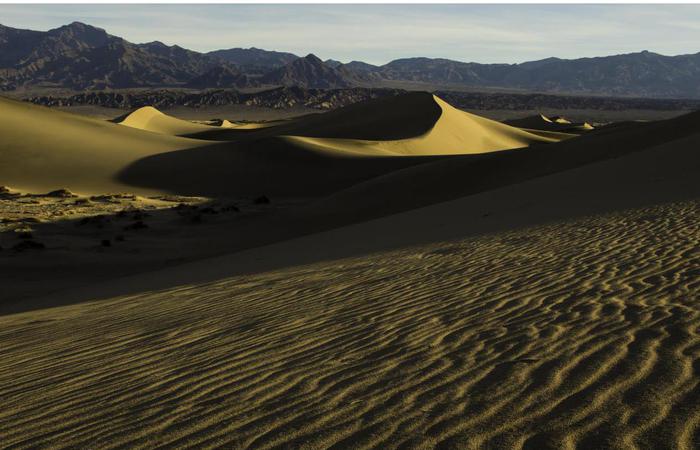

VIEW TIMELINENestled deep within the sprawling Bradshaw Mountains of central Arizona, the geothermal waters at today’s Castle Hot Springs resort have enthralled countless guests for generations. Indeed, their use has seemingly harkened back centuries, with the Native American Yavapai visiting the site frequently. The Yavapai even sought to keep the location a secret, wishing to safeguard the medicinal properties they felt the springs possessed. However, European American settlers stumbled onto the site amid the rampant land speculation that surged throughout the Arizona territory in the middle of the 19th century. Although definitive accounts recording the discovery are absent from the historical record, surviving oral tradition stipulates that word of the springs’ existence had gradually spread among the throngs of prospectors who were crawling through the mountains in search of mineral deposits. The prospectors, in turn, eventually encountered the oasis, bathing in its warm, tranquil waters after a long day of surveying. Enterprising entrepreneurs then acquired the site in the wake of the American Civil War, recognizing its potential to evolve into a popular retreat. Those proprietors specifically hoped to incorporate the springs as the foundation for a wellness resort that healed chronic health conditions like rheumatism and tuberculosis, eventually making it one of the most renowned historic hotels Phoenix has to offer.

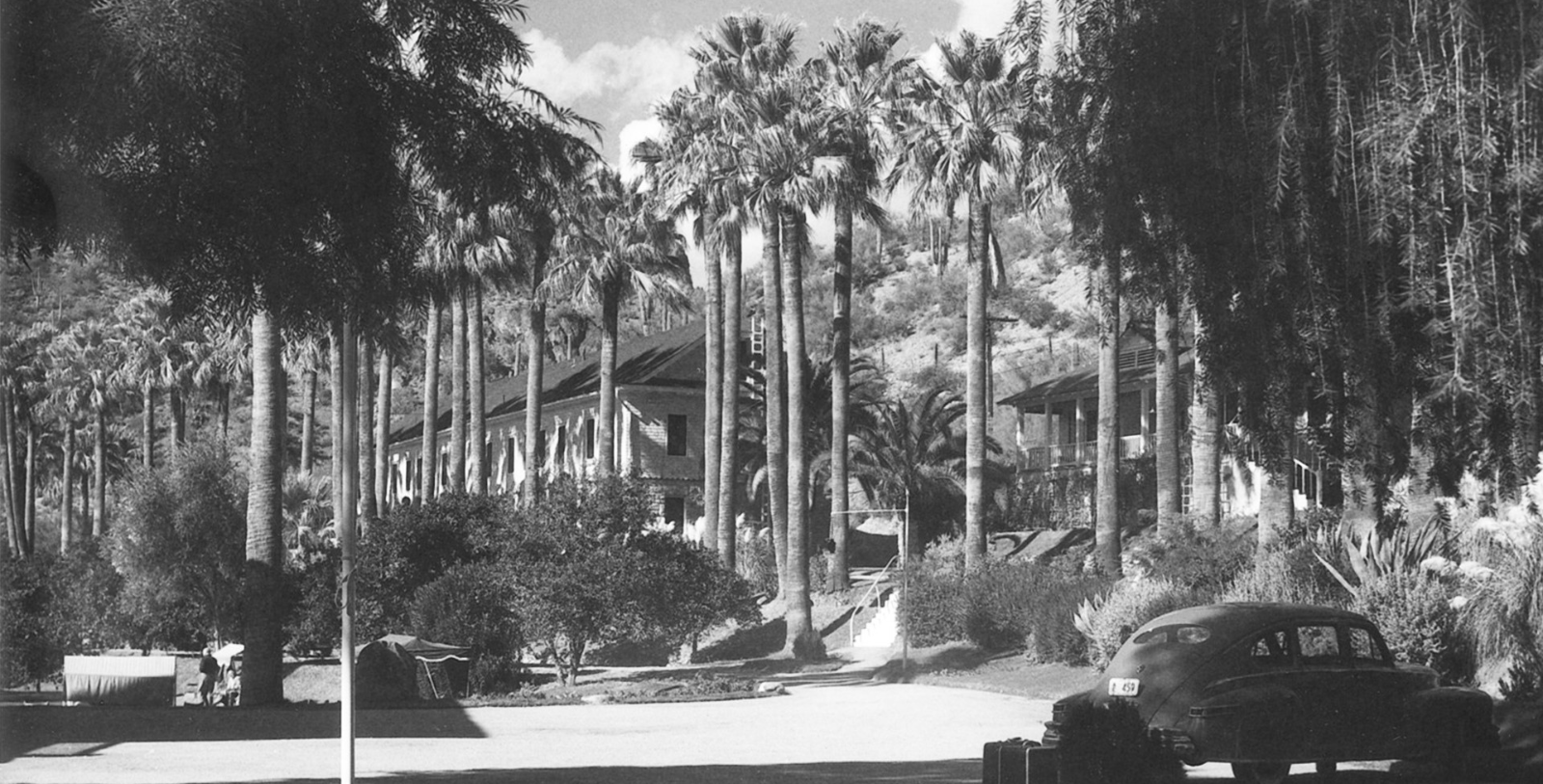

One owner—Thomas Mann—had even constructed a rudimentary boarding house next to the pools, which attracted all kinds of outdoor adventurers from across the country. But the springs’ fate changed forever when mining magnate Frank M. Murphy bought their property rights during the 1890s. Wishing to redirect the appeal of the site more toward recreation, Murphy began an extensive building project that led to the creation of a serene resort complex called “Castle Hot Springs.” (The name was derived from the surrounding landscape, which seemed to resemble castle parapets.) Dozens of unique structures soon encapsulated the springs, starting first with the historic Palm House and then the quaint Administrative Building. Murphy had spared no expense either, ensuring that the gorgeous new Castle Hot Springs exceeded the expectations of his then-contemporary travelers. Murphy had even invested heavily to create a dedicated railroad line and accompanying country road to help ferry his guests from the nearest transportation hub of Hot Springs Junction. Much to Murphy’s delight, the new Castle Hot Springs emerged as a renowned retreat when it finally opened for business in 1896. Tourists quickly flocked to the resort from across the United States, allured by tales of its serene setting and pleasant climate.

Stories about the springs’ rejuvenating abilities proved to be particularly charming, gaining the attention of influential figures from families like the Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and Astors. Prominent intellectuals—such as painter Maxwell Parrish and author Zane Grey—also made the trip out to Murphy’s resort, who created fascinating works of art and literature that further reinforced the appeal of its setting. Numerous politicians traveled to the facility often as well, with one guest—Arizona Governor Nathan Oakes Murphy—temporarily moving the territorial capital to Castle Hot Springs whenever he arrived. (The governor was the business partner and brother to Frank M. Murphy.) Perhaps the most noteworthy guest to visit at the time was former President Theodore Roosevelt, who decided to stay on-site amid a trip to commemorate an eponymously named dam constructed nearby in 1911. The prosperity of Castle Hot Springs remained strong for many decades thereafter, too, even managing to withstand the financial tumult of the calamitous Great Depression. Tantamount to its success was the resort’s new proprietor Walter Rounsevell, who had come to own Castle Hot Springs following a long stint as its general manager. Under his watch, the resort’s operations expanded significantly as part of a grander strategy to better immerse guests into the culture of the American Southwest. Central to those novel experiences was exploring the undulating desert countryside on horseback alongside the professional cattle wranglers who managed ranches next to the resort. Many guests recounted the trips admiringly, considering them to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

However, this prosperity ended abruptly once America entered World War II. With domestic travel disappearing as such, Rounsevell leased the resort to the United States Armed Services to use as a recreational center for convalescing servicemen. Hundreds of wounded veterans subsequently spent weeks at Castle Hot Springs, relying upon its serenity to recover. In fact, future U.S. President John F. Kennedy was among the wounded sent to Castle Hot Springs following the destruction of his PT boat in the South Pacific. (President Kennedy enjoyed doing several activities during his stay at Castle Hot Springs, such as reviewing various Boston-area newspapers beside the pool.) Happier times returned to Castle Hot Springs as soon as the war ended though, with visitation quickly reaching prewar levels in a matter of months. By the mid-20th century, the resort had thus resumed its status as one of the best destinations in the whole region.

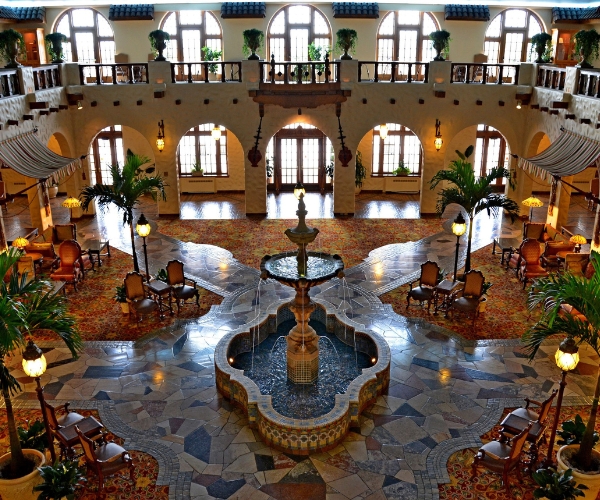

But tragedy struck when a harrowing structural incident affected numerous buildings throughout Castle Hot Springs unexpectedly mere weeks before Christmas began in 1976. Now facing an uncertain future, the resort unfortunately closed down for good. While a few enterprising individuals attempted to resurrect the facility over the next few decades, the historic Castle Hot Springs nonetheless remained vacant. Thankfully, the resort received a new lease on life when the Watt family acquired it for a sum of nearly $2 million in 2014. Dedicated to preserving its fascinating institutional history, they proceeded to enact a thorough renovation that brilliantly recaptured its Gilded Age character. The Watts family specifically sought to respect the architectural integrity of Castle Hot Springs’ various historic structures wherever possible, enlisting the help of accomplished preservationists to complete the job. The team painstakingly reconstructed the resort back to its former appearance right down to reconfiguring its original masonry. After months of hard work, the Watts finally reopened the historic Castle Hot Springs to great acclaim in 2019. Since then, Castle Hot Springs has reestablished its earlier repute as an extremely luxurious vacation getaway. Thanks to the efforts of the Watt family, the future of Castle Hot Springs has never looked brighter.

-

About the Location +

A tranquil oasis in Arizona’s picturesque Sonoran Desert, Castle Hot Springs has long offered its guests a wealth of thrilling outdoor experiences to enjoy. Central to those activities has been one of the most iconic geological fixtures in the desert’s northern environs—the surrounding Bradshaw Mountains. Named in honor of frontiersman William D. Bradshaw, the mountain range extends for some 40 miles on its north-south axis. Perhaps its most defining feature is its towering peaks, such as Mount Tritle, Mount Davis, and Mount Union. (Mount Union is the range’s largest mountaintop with an elevation measuring over 7,900 feet.) However, the Bradshaw Mountains also possess a fascinating human history that traces back millennia. While many Native American tribes inhabited the mountains for thousands of years, the most well-known were the Yavapai—specifically a subgroup referred to as the “Guwevkabaya.” The Yavapai lived throughout the region as hunter-gatherers, traversing the rugged mountain passes for wild game like deer, rabbit, and quail. They also formed fortified villages that cultivated a wide variety of crops, ranging from lamb’s quarters to saguaro fruits. Perhaps the most interesting economic endeavor that the Yavapai pursued was mining. Indeed, archeological evidence has revealed that the Yavapai discovered extensive copper deposits throughout the Bradshaw Mountains and fashioned ways to extract it from the earth.

The Yavapai thus succeeded in establishing a rich society in the heart of the Bradshaw Mountains that lasted until the arrival of the first European American settlers during the mid-19th century. Settlement by the settlers remained sparse at first, as most people who migrated through the range intended to reach the more populated California coastline miles away. But one wagon train managed to discover gold on their trek, setting off a significant population boom that continued for decades. Many of those pioneers were enterprising prospectors who were more interested in making a quick fortune mining rather than settling down permanently. (Among those early prospectors was the namesake of the mountain range, William D. Bradshaw.) It was soon common to see countless prospectors scattered across the Bradshaw Mountains, doing everything they could to find the next major lode of ore. So many prospectors had eventually reached the area that a network of some 40 diminutive yet prosperous mining towns had come to dot the landscape in just a few years. The mines themselves proved to be incredibly successful, too, with the largest one—Crowned King—collecting some $2-million worth of minerals over its lifetime. Nevertheless, the extensive land surveying gradually created tension between the Euro-American settlers and the local Yavapai, leading to armed conflict throughout the 1860s and 1870s. The Yavapai, in turn, lost the struggle and were ultimately confined to reservations north of the mountain range. (The Yavapai have continued to live in the area, where their descendants have endeavored to keep their legacy alive.)

Mining nonetheless remained the preeminent industry within the Bradshaw Mountains, providing an important source of employment for decades. However, the mines began to close permanently by the beginning of the 20th century as the price for rare metals became very unstable. Most of the small mining communities transformed into ghost towns in consequence, with the remaining residents turning to ranching and other agricultural endeavors instead. The federal government had also begun enforcing land conservation policies, which ultimately designated portions of the Bradshaw Mountains as a part of the 1.25-million-acre Prescott National Forest in 1908. Amazingly, the range’s pastoral character has managed to endure ever since, enabling the region to emerge as a renowned holiday destination. Prescott National Forest, in particular, has become a favorite place to explore due to its 950 miles of beautiful scenic trails. Furthermore, the location is host to many fantastic recreational hobbies, including camping, fishing, rock climbing, and general sightseeing. Guests do not have to drive far from Castle Hot Springs to enjoy the mountains' natural beauty either, as they can experience the landscape just beyond its front door. In fact, the resort offers direct access to five peaceful hiking trails in the Bradshaw Mountains: Agave Trail, Castle Peak Trial, Chocolate Drop Trail, Salvation Peak Trail, and Yavapai Trail. Guests will discover several exciting natural wonders when journeying along the nearly nine miles of trail pathways, too, such as the famous Wells Fargo Cave and Crater Canyon.

-

About the Architecture +

Castle Hot Springs today largely displays a reconstructed version of its original architectural style, which can best be described as “eclectic.” Dating to the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, historians today consider “eclecticism” to be part of a much larger movement to fuse together a variety of historical designs. Earlier in the 1800s, architects—particularly those in Europe—decided to rely upon their own loose interpretations of historical architecture whenever they attempted to replicate it. Such a practice appeared within such styles as Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Second Empire architecture. But at the height of the Gilded Age, those architects decided to use historic architecture more literally when developing a building. A few architects went a step further by combining certain historical styles together to achieve something uniquely beautiful. In some cases, those individuals felt inspired to add a new historical form onto a building that they were renovating—just like The Mansion at Ocean Edge. Ultimately, the architects felt that joining such architectural forms together would give them a new avenue of expression that they otherwise did not have at the time. They also believed that they had stayed true to the earlier forms, so long as their designs perfectly replicated whatever it was they wanted to mimic.

In Europe, this approach first appeared as a rehash of the Gothic Revival style known as “Collegiate Gothic.” The European architects then used such a mentality to influence the unfolding philosophies of the Beaux-Arts school of design and the emerging Renaissance Revival style. Many architects in America followed suit, the most notable of which were Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim. The American architects who embraced “eclecticism” were at first interested in the country’s colonial architecture. Much of the desire to return to the time period was born from the revived interest in American culture brought on by the Centennial Exposition of 1876. Pride in preserving the nation’s heritage inspired the architects to perfect the design principles of their colonial forefathers in new and intriguing ways. This interest gradually splintered into other revival styles, though, like Spanish Colonial and Tudor Revival. Some Americans even infused the approach with the popular Beaux-Arts aesthetics of France, such as Hunt and McKim. Yet, the birth of Modernism in the 1920s and 1930s eventually ended the worldwide love affair with “eclecticism,” for architects throughout the West became more enchanted with the ideas of modernity, technology, and progress.

-

Famous Historic Guests +

Zane Grey, author best remembered for his novel Riders of the Purple Sage

Maxfield Parrish, painter and illustrator best remembered for his saturated hues and neoclassical imagery

Cecil B. DeMille, director known for filming movies like The Ten Commandments, The Greatest Show on Earth, and Samson and Delilah

Nathan Oakes Murphy, 10th and 14th Governor of Arizona Territory (1892 – 1893; 1898 – 1902)

Richard Elihu Sloan, 17th Governor of Arizona Territory (1909 – 1912)

Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States (1901 – 1909)

John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States (1961 – 1963)

-

Film, TV, and Media Connections +

The Squaw Man (1914)