Receive for Free - Discover & Explore eNewsletter monthly with advance notice of special offers, packages, and insider savings from 10% - 30% off Best Available Rates at selected hotels.

history

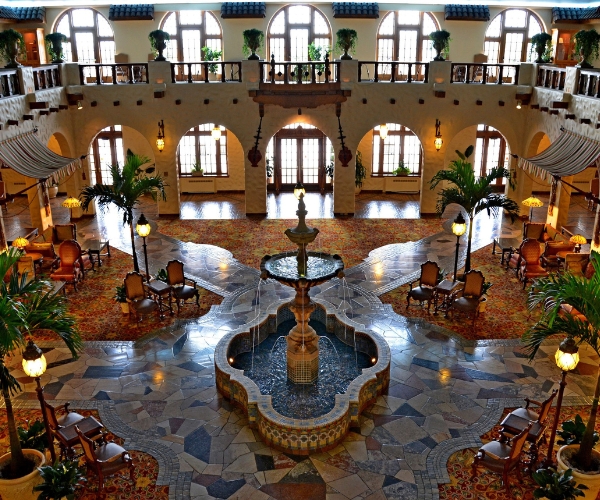

Discover Boar’s Head Resort and Birdwood Mansion where the restaurant and main inn feature stunning architectural elements, including wooden beams and flooring repurposed from a nearby gristmill dating back to the 1830s.

Boar’s Head Resort and Birdwood Mansion, a member of Historic Hotels of America since 2001, dates back to 1834.

VIEW TIMELINENestled right outside of downtown Charlottesville, Virginia, Boar’s Head Resort and Birdwood Mansion and Birdwood Mansion is a fantastic holiday destination steeped in history. The origins of this fantastic vacation getaway harken back to the early 18th century, when the area first began hosting a quaint tavern. Remembered as "Terrell's Ordinary," the business served the countless colonial pioneers then traveled further inland toward the Blue Ridge Mountains. The site attracted the attention of Thomas Jefferson, who stumbled upon it in 1800. Coming to adore its inherent beauty, Jefferson subsequently encouraged his friend Eliza Trist—a fellow member of the Confederation Congress—to buy the now-vacant lot. (Jefferson lived nearby, with his plantation, Monticello, located a mere few miles away on the other side of Charlottesville.) While Trist was receptive to the idea, it would be his son, Horé Browse Trist, who would acquire the land during the early 19th century. The younger Trist in turn set about developing the new estate over the following years, calling it "Birdwood" after a county official he had met earlier in England. But Birdwood remained a part of the Trist family for just a brief time, as local leader William Garth came to acquire Birdwood in 1819. Garth immediately commissioned several construction projects that changed the appearance of Birdwood. His most significant contribution to the hotel was the creation of a gorgeous manor placed at the center of the estate, which also went by the name "Birdwood."

The home’s architecture proved to be breathtaking, showing characteristics common to the pavilions on the lawn at the University of Virginia and other residences constructed by Thomas Jefferson's builders. Birdwood earned a great reputation under Garth's ownership over the next few decades, specifically becoming renowned for its successful farming operations. The estate soon became home to a variety of outstanding agricultural facilities, including a towering grist mill designed by an associate of Thomas Jefferson named Martin Dawson. In fact, Birdwood emerged as the birthplace for the "Hole and Corner Club," which spearheaded many interesting experiments that sought to enhance crop returns. Nevertheless, the estate would remain a prosperous enterprise well after Garth's death in 1860, with his descendants taking over its daily activities. But the outbreak of the American Civil War erupted not long thereafter, resulting in Virginia becoming a battleground throughout the duration of the conflict. Union scouts even pillaged Birdwood in 1865, although General George Armstrong Custer stopped the destruction before it affected the entire estate. Fortunately for the Garth family, some of the historic farm buildings managed to endure the raid, including Dawson’s ingenious gristmill. Despite its survival, Birdwood nonetheless experienced years of unstable ownership in the wake of the war. However, two owners—Hollis Rinehart and Henry L. Fonda—would initiate their own respective renovations that sought to help revitalize the estate throughout the early 20th century.

But in 1959, real estate developers John Rogan and John Rhea bought the land adjacent to the Birdwood estate. Recognizing the area's potential as a premier retreat, the two started building an amazing boutique hotel known as "Boar's Head Inn." Amid the construction, Rogan had discovered the now-derelict gristmill and lamented its poor condition. Intent on saving it from further decay, he incorporated its surviving components within the greater structure of the nascent hotel. After years of construction, the Boar's Head Inn debuted before considerable acclaim in 1964. The site subsequently emerged quickly as one of the region's most celebrated destinations, gradually reaching the size of an actual resort by the end of the century. Then during the 1980s, the University of Virginia Real Estate Foundation—which had obtained the neighboring Birdwood estate some two decades prior—purchased the Boar's Head Inn, financing renovations and improvements to guestrooms, restaurants, public areas, and even athletic facilities. Incorporating the land of the erstwhile Birdwood estate, the University of Virginia went on to transform Boar’s Head Inn into a magnificent 600-acre destination! Celebrated as "Boar’s Head Resort and Birdwood Mansion" today, this amazing location has since preserved its incredible reputation as a luxurious vacation hotspot. The University of Virginia has striven to preserve its heritage as well, investing millions of dollars toward ensuring its continued upkeep. The future of Boar’s Head Resort and Birdwood Mansion has truly never looked brighter.

-

About the Location +

The city's history harkens back to the mid-18th century when European settlers began establishing the first homesteads throughout the region. Over time, a few of those enterprising pioneers started to conduct trade along a thoroughfare known as the "Three Notched Road," and formed a small village in the process. The local leaders of the surrounding Albemarle County in turn decided to officially charter the community in 1762, calling it "Charlottesville" after the wife of the reigning British King George III, Queen Charlotte Sophia of Mecklenburg. Although the settlement remained small for many years after, it thrived as a regional economic center due to the continued trade along the Three Notched Road and the nearby Rivanna River. But its diminutive nature did not dissuade influential people from moving to the vicinity, either. Indeed, one of the most significant figures in Charlottesville's history was Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States and the principal author of the Declaration of Independence. In 1768, Jefferson specifically began constructing a beautiful mansion atop a hill right outside of town. Called "Monticello"—or "little mountain"—Jefferson had designed the structure based upon the neoclassical principles of the great Italian architect Andrea Palladio.

Jefferson's blueprints incorporated some of the most recognizable elements of Palladian motifs, such as symmetry, classical forms, and harmonious proportions. But the house featured several distinctive architectural innovations, like an octagonal room, a revolving bookstand, and a dumbwaiter for wine. While Monticello was celebrated for its architectural beauty, it was nonetheless a working plantation that relied on the labor of enslaved Black people. In fact. Jefferson owned over 600 Black slaves during his lifetime, and their contributions were integral to the estate’s operations. (Among the enslaved families living at Monticello were the Hemings, whose member, Sally, is believed to have had a long-term relationship with Jefferson.) Jefferson would spend the rest of his life at Monticello, pursuing an extensive variety of projects that fueled his passion for agriculture, architecture, and technology. His most notable endeavors involved the creation of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville during the early 19th century. Envisioning the campus to serve as an "academical village," Jefferson hoped the school would foster a greater community where students and professors could learn together. He subsequently worked alongside noted architect Thomas R. Blackburn to craft its initial layout, going as far as to design a few of the buildings—including its famed Rotunda—directly.

Meanwhile, Charlottesville kept growing steadily, eventually reaching the scale of an actual city by the middle of the century. Its continued economic prosperity eventually made it a strategic asset during the American Civil War, too, functioning as an important Confederate supply base for units stationed all over Virginia. After the war, Charlottesville, like much of the American South, faced the challenges of Reconstruction and the long struggle for civil rights. This fight persisted well into the 20th century in consequence, with Charlottesville emerging as a focal point for the wider Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Nevertheless, Charlottesville today has also become celebrated for its rich diversity, vibrant arts scene, and fascinating cultural institutions. Cultural heritage travelers have especially enjoyed visiting renowned landmarks like the Historic Downtown Mall, Jefferson Theater, IX Art Park, President James Madison's Highland, and the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center. Two of its most famous historic sites—the University of Virginia and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello—are even designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites! From its colonial roots to its modern-day struggles and triumphs, the city embodies the spirit of America—a place where history is ever-present, and the future is continually being shaped.

-

About the Architecture +

Boar’s Head Resort and Birdwood Mansion possesses a unique architectural style that can best be described as "eclectic." Dating to the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, historians today consider "eclecticism" to be part of a much larger movement to fuse together a variety of historical designs. Earlier in the 1800s, architects—particularly those in Europe—decided to rely upon their own loose interpretations of historical architecture whenever they attempted to replicate it. Such a practice appeared within styles like Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Second Empire architecture. But at the height of the Gilded Age, those architects decided to use historic architecture more literally when developing a building. A few architects went a step further by combining certain historical styles together to achieve something uniquely beautiful. And in some cases, those individuals felt inspired to add a new historical form onto a building that they were renovating—just like Boar’s Head Resort and Birdwood Mansion. Nevertheless, the architects felt that joining such architectural forms together would give them a new avenue of expression that they otherwise did not have at the time. But they even believed that they had stayed true to the earlier forms, so long as their designs perfectly replicated whatever it was, they wanted to mimic.

In Europe, this approach first appeared as a rehash of Gothic Revival-style known as "Collegiate Gothic." The European architects then used such a mentality to influence the unfolding philosophies of the Beaux-Arts school of design and the emerging Renaissance Revival-style. Many architects in America followed suit, the most notable of which being Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim. The American architects who embraced "eclecticism" were at first interested in the country's colonial architecture. Much of the desire to return to the period was born from the revived interest in American culture brought on by the Centennial Exposition of 1876. More specifically, pride in preserving the nation’s heritage inspired the architects to perfect the design principles of their colonial forebearers in new and intriguing ways. This interest gradually splintered into other revival styles though, like Spanish Colonial and Tudor Revival. Some Americans even infused the approach with the popular Beaux-Arts aesthetics of France, such as Hunt and McKim. However, the birth of Modernism in the 1920s and 1930s eventually ended the worldwide love affair with "eclecticism," for architects throughout the West became more enchanted with the ideas of modernity, technology, and progress.